How Frances Ha Captured the Romance and Precarity of Present-Day New York

Noam Baumbach and Greta Gerwig Discuss the Social Critique at the Heart of the Movie

“I know the city so well, and I’ve spent most of my life here,” Noah Baumbach explained, while promoting the release of Frances Ha (2012). “So I’m drawn to it, and I think I get a lot of ideas from the city. If I’m shooting on a street that I have memories of, there’s always something extra about just showing up to work every day, even if there’s no literal connection to the scene I’m shooting.”

Baumbach was raised in a Brooklyn intellectual family; his parents were film critics and novelists. He worked as a messenger for the New Yorker before writing for its “Shouts and Murmurs” section; he studied English at Vassar, and his time there (and immediately after) inspired his debut feature, Kicking and Screaming (1995). That film, though set at an unnamed East Coast university, was shot in Los Angeles; his sophomore effort, Mr. Jealousy (1997), was his first New York production. He spent the next eight years writing screenplays with Wes Anderson and going to therapy, and his next directorial effort, The Squid and the Whale (a semi-autobiographical reflection of his parents’ divorce), was the result of both. It was nominated for an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.

His next feature, Margot at the Wedding, wasn’t as well received; critics complained that it was too sour and cynical. His next screenplay was of a similar spirit, the story of a cranky New Yorker on an extended visit to Los Angeles, where he does not feel at home. Ben Stiller was cast in the title role in Greenberg, and Baumbach set about auditioning actors for the role of Florence, the romantic interest. And that was how he met Greta Gerwig.

Gerwig, a native of Sacramento, California, came to New York to attend Barnard, where she studied acting and playwriting. Her cinema education came from Kim’s Video on St. Mark’s, where she rented armloads of foreign and independent movies; after her mind was thoroughly blown by Claire Denis’s Beau Travail, she realized that directing was something she could, and should, do. But after failing to land in any MFA programs for playwriting, she focused on acting, becoming the go-to ingénue of the “mumblecore” movement, acting for Joe Swanberg (Hannah Takes the Stairs, 2007) and the Duplass Brothers (Baghead, 2008), among others.

Most of those films were improvised, which Gerwig assumed was why Baumbach put her through so many auditions: “There was a little bit of ‘Do you know what you’re doing? Can you do this in a controlled way, or are you just some weird person who has no shame?’” But she stole the movie and captivated its director. “Greta has old studio-system chops,” he said. “Carole Lombard, Katharine Hepburn, they could be in something totally dramatic, or totally funny; they could sing, they could dance.”

Nearly every reviewer singled out Gerwig as the highlight of Greenberg, but the film itself never found an audience. Baumbach next attempted to adapt Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections into an HBO series; the network passed, and the costly endeavor left the filmmaker feeling unsatisfied. He wanted to bounce back with something simple and enjoyable.

So he sent Greta Gerwig an email. There was something “authorial” about her acting, he wrote. He wanted to make another movie with her, and thought maybe they could write it together.

“It’s something that I related to in the Frances character, which was this idea of having a fantasy of the city and wanting to have that experience, with the city pushing back.”

Not since NYC was the movie capital of the world—that’d be between 1894 and 1917—has so much filming been done here,” wrote the New York Post’s Reed Tucker in the fall of 2011. “Last year, some 200 films were made in Gotham and this television season, a whopping 23 primetime series are being filmed here. That’s a record, and a change from previous decades when even the exterior shot used for Seinfeld’s ‘Upper West Side’ apartment was a building in LA.”

Much of this activity was thanks to the ongoing production tax credits—$420 million a year by the early 2010s, according to the New York Daily News—but in the post-9/11 years, attitudes across the country had shifted. The East Coast freak show was now, strangely, seen as part of the nebulous, mostly rhetorical “real America.” Tourism continued to boom, boosted by Mayor Bloomberg and his tax-exempt corporation NYC & Company, which invested considerable financial resources toward a goal of luring 50 million tourists per year to Gotham by 2015, and hit it four years early.

But by the 2010s, what exactly were they visiting? “Present-day New York has been made to attract people who didn’t like New York,” noted essayist Fran Lebowitz. “That’s how we get a zillion tourists here, especially American tourists, who never liked New York. Now they like New York. What does that mean? Does that mean they’ve suddenly become much more sophisticated? No. It means that New York has become more like the places they come from.” A reverse white flight was in full swing (urbanist Richey Piiparinen dubbed it “white infill”), in which the children and grandchildren of those who had fled to the suburbs in the seventies and eighties moved to the city for the adventure their elders had abandoned, but demanded the comforts of their suburbs when they got there.

And thus, as the 21st century continued, New York City’s discount stores, coffee shops, pizzerias, diners, and restaurants were replaced by Target, Starbucks, Papa John’s, IHOP, and Chick-fil-A. (When the evangelical chicken chain opened in 2015, customers lined up in the rain overnight. One of them, a 24-year-old Georgia transplant, told the New York Post, “I have been waiting for this for a year and a half now, since I came to New York.”) Union Square boasts The Strand and its “18 miles of books,” but those intimidated by its high shelves and surly clerks can retreat to the Barnes & Noble across the way. In Times Square, steps from the authentic Italian food of restaurant row, tourists and transplants fill the tables of a three-story Olive Garden. “America has gotten its revenge on New York,” Lebowitz said, “because it’s moved right in. Now it is a mall.”

And not many great movies are set in malls. But in the Bloomberg era, the city (and its stories) had been all but devoured by the ultra-wealthy—so The City reflected on-screen, in contemporary cinema, didn’t just feel like a different era from the New York of earlier decades. It felt like another continent. A drab, flavorless one.

Baumbach had very clear ideas about how he wanted to make his next movie: low-budget, shooting on digital video, with a small crew, guerilla-style. But he wasn’t sure what it was about. “I just had more general ideas that it would be something in New York and something in black and white and something with Greta,” he says. “But I suppose I had an instinct, to kind of involve her in the process of coming up with what it was going to be.”

Gerwig was flattered by the offer, but only to a point; when he told her it was going to be “very stripped down, bare-bones,” she says, “I think part of it was, he was like, ‘You’re cheap, right?’” She was also intimidated, sitting on the list she composed of ideas for characters and scenes (“three pages of stuff”) for days before sending it back to Baumbach. “He said, ‘This looks pretty great,’ and he started adding ideas, and then this document just started growing and that became the script.”

That script told the story of Frances (Gerwig), a young dancer who finds herself set adrift when Sophie (Mickey Sumner), her roommate and bestie, moves out of their apartment to cohabit with, and eventually marry, her longtime boyfriend. The void left by Sophie’s exodus deepens; Frances tries on new friends and new apartments but none of them seem right, and her career isn’t going anywhere, and should she even be here?

“It felt like a really natural collaboration,” Gerwig says. “I didn’t ever feel like either one of our voices was compromised in it. Though he’s clearly the more accomplished of the two writers, he was never like ‘Which one of us has an Academy Award nomination and which one of us doesn’t?’ Although he could have said that!”

From the beginning, they focused on a few key ideas. Frances Ha opens with what looks like a conventional NYC rom-com montage—frolicking in the city, eating al fresca, snuggling on the subway, etc.—but the subjects, Frances and Sophie, aren’t romantically intertwined. “When we figured out that the Sophie/Frances relationship was going to be the through-line,” Gerwig says, “then we actually went through the script and tried to beat it out like a romantic comedy: She has the girl, that’s perfect, she loses the girl, she gets angry, she tries to get the girl back, she tries to make the girl jealous, and she rejects—like, we were trying to actually do that arc within the friendship.”

The New York Times’s Zach Baron noted the picture’s contradictions: “It is a deeply romantic film with no real romance at its center, a love letter to a city that is depicted, at times, as anything but lovable.”

That contrast was rooted in the film’s biggest stylistic influences. “I was thinking of Woody Allen’s movies with Gordon Willis, that they did in black and white,” Baumbach says. “He was sort of bringing a grand, cinematic gesture to a thing that was kind of intimate, story-wise. It was intimate and interpersonal, and he was sort of telling it in a big way.” The combination of returning to the city after the LA-set Greenberg and shooting, for the first time, in black and white “allowed me to see the city in a fresh way.”

The visual romanticism was also baked into the experience of the writers. “I’m from Brooklyn, she’s from Sacramento, and we both saw the city as a place that we might one day come to if we were able,” he told the A.V. Club. “I always saw Manhattan as a place that maybe one day I’d be able to live. The joke on me is that now that I live in Manhattan, everyone’s moving to Brooklyn.”

“You can’t live a bohemian life there anymore without money.”

Moving weighs heavily on Frances Ha, as it does for New Yorkers in general, and its impact is articulated by the picture’s ingenious structure: The chapters of Frances’s adventure are organized not by numbers or titles, but by the various addresses where she finds herself residing. “It was anthropologically right,” Baumbach explains, “but it was also thematically right because it was about movement—sort of perpetual movement where you’re not really going anywhere, or maybe lateral movement.”

Finding affordable housing was, to put it mildly, not a problem unique to their protagonist. Throughout the decade, the already pressing housing crisis in the city worsened; after a brief dip following the recession, rents continued to soar, the vacancy rate remained low, and landlords found new ways to deregulate rent-regulated apartments. Supply simply couldn’t keep up with demand, at least for those who couldn’t afford the luxury apartments the Bloomberg administration was incentivizing; even buildings that provided the token number of (arguably) affordable units required by those tax exemptions and bonuses forced those residents to use a separate entrance, soon dubbed the “poor door.”

“Now, to make films about New York, you basically make films about Wall Street,” said film critic Amy Taubin. “You make films about bankers. It has become a city, especially in Manhattan and Brooklyn, of extremely wealthy people.” Those economic woes, particularly for young artists, make for some of the most relatable moments in Baumbach and Gerwig’s Frances Ha script: Frances awkwardly asking her boss for more classes to teach; treating a pal to a celebratory dinner when her tax return arrives (only to find herself running to an ATM after the check is delivered at the cash-only restaurant); asking her trust-fund roommates, with some urgency, “Do you know that I’m actually poor?”

“I think anyone who’s an artist or an actor or a writer or doing anything that’s at all difficult or precarious or unlikely that they’ll ever be successful at always feels very close to the person who’s not doing it and who’s falling apart,” Gerwig says. “It’s not that in my life I’m so successful and together and then in movies I play these crazy people who are falling apart and unsuccessful. It’s that the outside narrative of success is not how it feels internally.”

But there was also something specific to the time and place, Baumbach said, that made this theme so present. “It’s something that I related to in the Frances character, which was this idea of having a fantasy of the city and wanting to have that experience, with the city pushing back,” he said. “It goes with the photography of the movie. It was a chance to shoot the city in the most beautiful way possible, while shooting a character who’s dealing with the economic realities of living in New York right now, which are not romantic. You can’t live a bohemian life there anymore without money.” (Or, as Sophie puts it, “The only people who can afford to be artists in New York are rich.”)

New York had seen wealth gaps before. But it was more extreme in this era of widening income inequality and systemic “hyper-gentrification,” a term used by Jeremiah Moss in his essential history/protest Vanishing New York (“gentrification on speed, shot up with free-market capitalism”). A staggering 21 percent of Manhattan residents were living below the federal threshold for poverty by the time Frances Ha hit theaters in 2013. The top 5 percent of households there were earning 88 times as much as the bottom 20 percent. It was, according to Census Bureau data, the greatest dollar income gap of any county in America.

There were protests—most notably, the group that dubbed itself Occupy Wall Street and took over Zuccotti Park in the heart of the financial district in the fall of 2011. They generated headlines and captured conversation for two months, until Mayor Bloomberg sent the NYPD to clear the park in a middle-of-the-night raid, executed like a paramilitary strike (complete with advance, counterterrorism-style “disorder training” and a media blackout). His office claimed “the occupation was coming to pose a health and fire safety hazard to the protestors and to the surrounding community.” And the “surrounding community,” New Yorkers knew, was always Bloomberg’s chief concern.

__________________________________

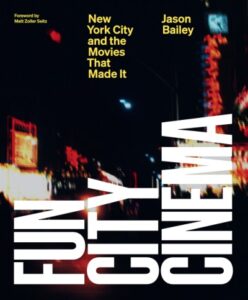

Excerpted from Fun City Cinema by Jason Bailey. Used with the permission of Abrams Books.

Jason Bailey

Jason Bailey is a film critic and historian. A graduate of the Cultural Reporting and Criticism program at NYU's Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute, and the former film editor of Flavorwire, his work has appeared in the New York Times, Vulture, Slate, VICE, the Atlantic, Salon, the Guardian, Rolling Stone, The Playlist, The Dissolve, and Crooked Marquee. He lives in the Bronx with his wife and two daughters.