How Final Fantasy VII Taught Me to Write

Jamil Jan Kochai on Character Building, Storytelling, and Cloud Strife

You’re twelve years old. You’ve just picked up Final Fantasy VII from a bargain bin at the K·B Toys in Natomas, not knowing a thing about its popularity or critical acclaim. “Only 14.99!” you tell your father, who makes less than that in an hour, but he’s in a good mood and you scored well on your STAR tests, so when you get home, you pop in the game, breathe in that PlayStation startup music, and begin.

The opening shot is of space, a dark void filled with distant stars that seamlessly transition into specks of light in an alley. A young girl’s face (Aerith) materializes out of darkness, just before the camera pans out to reveal a dystopian metropolis called Midgar. In the center of the city, the headquarter for the all-powerful Shinra corporation looms over the landscape. A couple of quick cuts to a rumbling train, before the camera zooms back in on the city, on a spiky headed, polyconic mercenary named Cloud Strife, whose first mission, you find out, is to blow up a Shinra energy reactor on behalf of Avalanche, an environmental insurgent organization.

Much of what makes Final Fantasy VII an incredible feat of storytelling is encapsulated in this opening scene. The cinematic visual language, the way it gives us a lay of the land. The political and economic complexities: Space! Corporations! Insurgency! Urban Development! From the outset, Midgar is depicted as an absurdly dystopian city, and yet, through its portrayal of class segregation, corporate hegemony, and environmental degradation, Midgar still mirrors many of the oppressive structures prominent in our own world. In this way, the game attempts to prepare you for the heavy, convoluted storylines that are ahead.

Refusing to remain static or single dimensional with its storytelling, the game repeatedly breaks out of its own narrative form, all for the sake of the ever-widening story itself.After you blow up the reactor and attack Shinra Headquarters, you discover that the main antagonist of the game up to that point, President Shinra, has already been killed by the legendary Sephiroth, a fearsome warrior and Cloud’s former mentor. It is only then that you realize that Midgar is just one city in a world filled with cities and towns and rivers and oceans and mountains and caves and beaches and airplanes, and your entire conception of the game is shattered.

The narrative transforms from a linear plot with a single pathway forward to an open world videogame with side quests and towns to explore. The story opens up to the player. The world feels full and fleshed out, complete with well-rounded characters who surprise us. Refusing to remain static or single dimensional with its storytelling, the game repeatedly breaks out of its own narrative form, all for the sake of the ever-widening story itself. But even as Final Fantasy VII expands outward in terms of form and gameplay, it also refocuses on an internal exploration of its characters.

Let’s start with Cloud.

He’s a former 1st Class SOLDIER and a mercenary. He has no ideals and doesn’t care about anyone else. To be frank, he’s a bit boring. That is, until he meets Aerith. Almost immediately, there’s a chemistry between them. Yes, yes, I know they’re made of pixelated polygons and the dialogue is written on screen and there are no facial expressions, and yet, it was undeniable to me.

She’s the first character to really disarm Cloud, teasing and flirting with him. At one point, she even convinces our hyper-masculine hero to dress up and seduce a mafia boss. They tell stories. They go on dates and act in a play together (yet another example of the network of stories this game puts forth). They learn to care for each other.

It’s memories, it’s scenes, it’s conversations. It’s character development, it’s storytelling. And it’s absolutely harrowing.And here’s where the scope and the form of the videogame plays a crucial role in the storytelling experience. You spend hours with Aerith, fighting monsters, escaping goons, and carrying out long conversations. You become emotionally invested in the relationship. In fact, there are multiple moments throughout the game where you can actually choose what to say to Aerith, which impacts the storyline and your relationship with other characters. When I chose lines of dialogue for Cloud, I could immediately feel the weight of that decision. It was strangely exhilarating—as if I were writing the story myself—and it was a feeling I carried with me into my own stories, my own dialogue, many years later.

The videogame, as a storytelling medium, provides its audience with an added layer of interaction and immersion. You hold the controller. You choose how to fight. You choose where to go, what to say. And so, halfway through the game, when Aerith is praying for the salvation of the world in an ancient temple, and Sephiroth falls from the sky and stabs her in front of you, you feel oddly implicated in the death. You hold your controller, and you feel helpless. The devastation is even more pronounced because her loss lingers with you in the game. You keep all her weapons and accessories.

When you to return to Midgar later in the story, the church in the slums, the playground near Sector 7, and even the Wall Market seem to be haunted by Aerith’s loss. As a child, I’d cried for other characters, (Mufasa, Ash, the Iron Giant), but Final Fantasy VII taught me how to properly mourn a character’s death, how their loss should haunt all of the other elements of a story: setting, plot, and, most importantly, character development.

Shortly after the death of Aerith, when Cloud finally tracks and confronts Sephiroth again, he comes to discover that much of his own identity, his past, has been fabricated. He was never a 1st Class SOLDIER, and he wasn’t mentored or trained by Sephiroth. This revelation eventually leads to one of the most unforgettable levels in the game, another narrative innovation.

You enter a physical manifestation of Cloud’s subconscious. An ethereal, cosmic space with planets and stars in the background, pillars and platforms arranged in the center, and a giant, translucent Cloud clutching his head, floating above. Soon, you realize your primary objective is to repair Cloud’s fractured psyche one repressed memory at a time. You approach different versions of Cloud, from varying points in time, and you parse through his memories, both real and invented. There are no battles. No monsters. No weapons or upgrades. You don’t accumulate experience points. Even the visuals aren’t technically impressive. But it’s thirty minutes of pure character exploration.

It’s memories, it’s scenes, it’s conversations. It’s character development, it’s storytelling. And it’s absolutely harrowing. Cloud’s character, or the persona Cloud has developed in response to trauma and memory loss, is gradually deconstructed. Through flashback scenes, Cloud’s old memories are laid bare and picked apart and reversed, and, in this way, Cloud’s character is given a whole new depth. You delve into his most intimate secrets, his deepest insecurities, and you’ve never cared for him more. You’ve already lost Aerith, and you can’t imagine losing Cloud, not now, not when you seem so close to redemption.

Each memory rediscovered, each story retold, feels as if you are pulling Cloud back from the oblivion of fragmentation, and though he’s not whole, exactly, his fragments are threaded together—however tenuously—into one complicated and contradictory character. In the end, that’s how he is rescued, and it’s as if the game is saying to you: “You can save yourself; you can put yourself back together, through your stories.”

At least, that’s what I heard.

___________________________

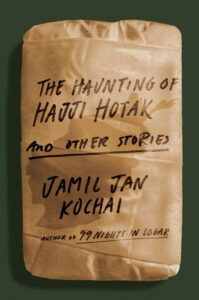

Jamil Jan Kochai’s The Haunting of Hajji Hotak and Other Stories is available now from Vintage.