Emmett Till’s death and the Black newspapers that came into my Pennsylvania home created a great vulnerability and fear of all things Southern in my teenaged mind. When my parents announced in 1957 that we were relocating to Atlanta, I was filled with dread. Emmett Till’s death had frightened me. But in the fall of 1957, a group of Black teenagers encouraged me to put that fear aside. These young people—the nine young women and men who integrated central High school in Little Rock, Arkansas—set a high standard of grace and courage under fire as they dared the white mobs that surrounded their school. Their names were Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrence Roberts, Melba Patillo, Carlotta Walls, Gloria Ray, Minnijean Brown, and Thelma Mothershed.

By the end of the 1956-57 school year, no schools in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, or Virginia had integrated. The southern states had passed 130 pro-segregation school laws, and an August 1957 Gallup poll showed a majority of Americans predicting race relations would get worse in the coming year; in the south, a two-to-one majority predicted the same.

President Eisenhower’s vacillation on civil rights encouraged the resistant white south. They knew there would be no strong federal effort to protect Black voting rights or integrate schools or to punish those who illegally opposed civil rights. On July 17, 1957, Eisenhower said at a press conference: “I can’t imagine any set of circumstances that would ever induce me to send federal troops . . . into any area to enforce the orders of a federal court.” The president’s desire to avoid direct involvement in school desegregation ended on September 24, 1957, in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Arkansas was an unlikely location for a showdown between federal and state authorities over school desegregation. In 1948, Arkansas became the first state to admit Black students to a state university without a court order. Immediately after Brown in 1954, the Little Rock school board announced a gradual plan that would begin integration with senior high schools in 1957, junior high schools in 1960, and elementary schools in 1963. The NAACP challenged the plan as too slow but lost, and the Little Rock school board announced integration would begin at central High school in September 1957.

*

Daisy Lee Gatson Bates was born in Huttig, Arkansas, a town she described as a “sawmill plantation, for everyone worked for the mill, lived in houses owned by the mill, and traded at the general store run by the mill.” When she was eight, she discovered that the people she knew as her parents were, in fact, her parents’ best friends. Her mother had been killed by three white men when she resisted their attempt at rape; her father, despondent, had left town, leaving young Daisy with friends. L. C. Bates, who would become her husband, was born in Mississippi and educated at Wilberforce college in Ohio. He worked for newspapers in Colorado, California, Missouri, and Tennessee before returning to selling insurance in Arkansas.

By the end of the 1956-57 school year, no schools in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, or Virginia had integrated.Shortly after their marriage, the Bateses moved to Little Rock and founded their own newspaper, the State Press, in 1941. Both joined the NAACP after they arrived in Little Rock. In 1957, Daisy Bates was elected president of the Little Rock NAACP. Tireless crusaders, the Bateses had vigorously supported the 1954 Brown decision; their activism earned them many enemies among Arkansas whites. Their credit was cut off, and both were threatened. They were convicted of contempt for criticizing a court trial; the Arkansas supreme court reversed their conviction. Mrs. Bates was elected president of the Arkansas state conference of NAACP Branches in 1952.

By August 1957, local racists, supported by the Mother’s League of Little Rock, stepped up their opposition to integrating the schools and persuaded school superintendent Virgil Blossom to delay the entrance of nine Black students to central High school. On August 28, the Mother’s League asked a county court to block desegregation. That same day, Arthur Caldwell of the Us Department of Justice met with Arkansas governor Orval Faubus. Caldwell told Faubus the federal government wanted to avoid being involved in controversy over the integration of schools. Thus encouraged that he would not be restrained, Faubus began to move to prevent the schools from being integrated. On August 29, with Faubus arguing that gun sales were up and violence was therefore imminent, the county court issued a temporary injunction against desegregating Central High School. That same day, the final version of the 1957 civil rights act passed both houses of Congress.

School officials, backed by Mrs. Bates and the NAACP, filed suit in federal court, asking for an injunction against anyone who interfered with integrating the schools. Federal judge Ronald Davies ordered the integration to proceed, and the school board announced that central High school would open on September 3. On September 2, Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to the school’s grounds, and the school board told the nine students not to try to attend the school until the legal battle had been settled.

On September 4, the Black students tried to attend school, escorted by Daisy Bates and a group of Black ministers she had recruited. One of the nine, Elizabeth Eckford, had not gotten the instructions to meet at Bateses’ home beforehand to go together. She went alone and met a mob. Guardsmen that Faubus had ordered to the school turned them away. In a court hearing, Judge Davies ordered the FBI to investigate the governor’s claim that violence was imminent.

Three days later, on September 7, Judge Davies rejected a school board request for a delay, and on September 9 the judge asked the Department of Justice to file a petition for an injunction against the governor and two national Guard officers. Faubus was ordered to appear in court on September 20 to show why he should not be held in contempt. Faubus met with Eisenhower in Newport, Rhode Island, on September 14. Eisenhower thought he had obtained an agreement from Faubus to order the national Guard to admit the students; within two hours of the meeting Faubus changed his mind. On September 19, the day before his contempt hearing, Faubus’s lawyers tried to disqualify Judge Davies. at the hearing, Judge Davies issued an injunction barring Faubus and the National Guard from any further interference with the integration of Central High School. It had finally become clear to President Eisenhower and attorney General Brownell that Faubus never had any intention of allowing integration to proceed.

Arkansas was an unlikely location for a showdown between federal and state authorities over school desegregation.Little Rock mayor Woodrow Wilson Mann asked Brownell to assign U.S. marshals to the school. Brownell refused, saying that only the court could do so. Judge Davies refused in turn, saying he could not issue such an order without an official request from the Justice Department. Eisenhower was more worried about the harmful political consequences of the federal government forcing the integration of nine Black students and providing protection for them than the harmful violence that would result if he did not. earlier, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had refused to send FBI agents to Little Rock to police the school. The city only had 175 policemen; they had refused to escort the children to central High school, and the Little Rock Fire Department refused to provide hoses for crowd control.

On September 23, the nine Black students entered Central High school through a side door. Daisy Bates had again arranged for them to meet at her home to go together for safety. A screaming mob of several thousand whites gathered, and the students were trapped in the school. Finally, through the plan of one police official, the nine were spirited safely out of the building in station wagons, ducked down so the massive crowd outside didn’t see them. Daisy Bates issued a challenge to President Eisenhower: the students would not return until she had his word they would be protected. she had become the spokesperson for the students, their protector and defender.

Twenty-four hours later, US army paratroopers from the 101st airborne escorted the nine into the building and were stationed outside Central High School. The integration of Little Rock’s public schools had begun. That military protection would last the entire year—as would the harassment of the nine teenagers in the building.

The year before, Eisenhower had allowed school authorities and Texas governor Alan Shivers to defy a federal court order integrating schools in Mansfield, Texas. In 1957, in Little Rock, a reluctant president acted. National politics made the difference. Texas was a major prize for the republicans in the 1956 presidential race, and Governor Shivers was a personal friend and political ally of Ike’s. Arkansas was solidly Democratic; there was nothing political to be gained in Arkansas for Eisenhower by capitulating to Orval Faubus.

The Little Rock crisis energized American Blacks who watched the drama unfold on television. Unlike the Montgomery boycott of 1955 and 1956, the Little Rock school integration crisis in 1957 was told on television, as well as in daily national and international headlines. The Little Rock crisis had larger media elements than the Montgomery bus boycott. In Montgomery, the community fought primarily with local officials; in Little Rock, a governor fought with the president of the United States, and the president equivocated about protecting the safety and civil rights of nine young people against a white mob and hostile state government.

In Little Rock, state troops were used to stop integration; federal troops were used to enforce it and to finally stop the white mob. Little Rock had rabid white mobs attacking defenseless teenagers, the eldest only 16 years old, the youngest 14. Montgomery had an entire community, largely faceless, fighting a faceless evil—bus segregation. And unlike Montgomery, where Martin Luther King emerged as the dignified single spokesman for the entire community, the heroic figures in Little Rock were nine personable teenagers—selected from an 80-student pool of applicants—and a middle-aged Black woman. The evil in Little Rock had a face—the screaming mobs that gathered outside Central High School every day and the wily, duplicitous governor.

*

The most popular teenagers in the US in the fall of 1957 were Arlene Sullivan, Kenny Rossi, Justine Corelli, and Bob Clayton. Five afternoons a week, after school, beginning in August 1957, with other high school students from south Philadelphia, they appeared on a new television program called American Bandstand. “Every kid in America was watching the show,“ said its host Dick Clark years later. Bandstand’s regulars quickly developed fan clubs, becoming teenaged heroes and heroines. According to historian Richard Aquila, “The show became a live soap opera: would Carol be dancing with Joe today? Did you see Carmen’s new sweater? Why aren’t Bob and Justine dancing together? . . . Did you notice Pat’s new dance step?”

The Little Rock crisis energized American Black people who watched the drama unfold on television.But then, in September 1957, another group of teenagers came into my life, and the ones on American Bandstand danced out of my life. For Black young people, who had only one Black couple on American Bandstand to relate to, the Little Rock Nine quickly became heroes and heroines—a model for what a concerned Black teenager ought to be. Younger Blacks were especially thrilled by the courage of the Little Rock Nine who faced daily harassment from their white schoolmates. They were threatened, kicked, punched, spat upon—the objects of verbal and physical abuse—and set a high standard of grace and courage under pressure. Because their activities were so widely reported in both the Black and white press, and because the waiting world knew instantly when one was hurt or attacked, the personalities of each of the Little Rock Nine became well known throughout Black America. They were the poster children of the modern civil rights movement.

Minnijean Brown was the “bad” girl who wouldn’t take anything from anyone; when two white boys attacked her, she upset a bowl of chili on their heads. When a white girl called her “Black bitch,” Minnijean called her “white trash” and said, “If you weren’t white trash, you wouldn’t bother me!” A few days later, a white student upset a bowl of hot soup on her head. Because of her refusal to suffer in silence, she was expelled and graduated from high school in New York. A generation of young Black people worried with Minnijean, were angry when she was provoked to answer taunts with other taunts, and at the same time proud when she refused to take punishment without retaliation.

Elizabeth Eckford’s courage and calm demeanor in facing the mob the first day the students tried to attend school won her fans around the world. Ernest Green, at sixteen, was the oldest of the nine and the most mature; he was looked upon as their leader. Mrs. Bates showed a national audience that civil rights work was women’s work too. A professional woman and business owner, her profession and part-time work with the NAACP were all-consuming. In her middle age, she showed that civil rights activism could be work that consumed a lifetime.

Even before the school integration crisis, the Bateses had suffered incredible harassment: had their home attacked, their lives and livelihood threatened, their newspaper eventually strangled to death by an advertiser boycott. She argued with a governor and won. She gave the president of the United States an ultimatum, and he obeyed. Daisy Bates would not back down. Armed guards protected her home. She kept a .45 caliber automatic in her lap when she sat at home at night. Several of the women active in the early 1960s sit-ins said that Daisy Bates gave them a model of what a woman could be and should be—fierce in the face of opposition but a calm and reassuring presence to the nine Black students to whom she was surrogate parent and protector.

Finally, the Little Rock crisis, unfolding in the days and weeks immediately after passage of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, showed how irrelevant to civil rights the bill actually was. When in March of 1956, 101 members of congress signed the Southern Manifesto, they issued a prediction that violence would follow attempts to enforce the Brown decision. Common to mid-1950s school crises, whether in Little Rock or Prince Edward County, Virginia, were several themes. In Arkansas and Virginia, each state’s political leadership—Governor Orval Faubus in Arkansas and Senator Harry Byrd in Virginia—seized the school integration issue to rally white support at a time when their political futures seemed insecure. In both states, the NAACP’s reliance on the federal courts to enforce integration was turned on its head by segregationists, who knew that litigation could mean later, that later meant further delay, and that further delay might mean never. Without support from Eisenhower, only rarely could the courts overcome the mobilized white resistance. Defiance clothed in legalisms also encouraged extralegal, violent defiance.

*

On May 27, 1958, Ernest Green became the first Black student ever to graduate from Central High School. It was estimated that his diploma had cost the US taxpayers $5 million. But would he be the last? Or at best, the first for a long, long time? That same month, the Little Rock school board went back to federal court to ask that desegregation be postponed until January 1961—a delay of two and one-half years. This delay, the school board argued, was what the supreme court meant when it ordered desegregation to proceed “with all deliberate speed.” Citing “pupil unrest, teacher unrest and parent unrest,” they maintained: “The principle of integration runs counter to the ingrained attitudes of many of the residents of the District. For more than eighty years the schools have been operated on the basis of segregation. The transition involved in the gradual plan of integration has created deep rooted and violent emotional disturbances.”

Even before the school integration crisis, the Bateses had suffered incredible harassment: had their home attacked, their lives and livelihood threatened, their newspaper eventually strangled to death by an advertiser boycott.Their argument was that if Supreme Court decisions resulted in disagreement—or violence—then that violence should be rewarded by a stay (a delay of implementation) by the court. A trial was held before a federal district judge in early June; witnesses testified to “chaos, bedlam and turmoil,” and the court granted the school board the relief they had sought, suspending school desegregation until January 1961. In August, the Eighth District Court of Appeals reversed this: “The time has not yet come in these United States when the order of a federal court must be whittled away, watered down, or shamefully withdrawn in the face of violent and unlawful acts of individual citizens in opposition thereto.” But the school board, having lost the constitutional battle, nevertheless won a temporary procedural war; the court stayed its own order, delaying desegregation until after the opening of school.

The lawyers for the Black children went to the US Supreme Court. On August 25, the court scheduled a special term and set a hearing for August 28. The Department of Justice lined up foursquare behind the Black petitioners, recognizing that behind the immediate issue of school desegregation the power of the federal courts was at stake. After hearing arguments on procedural points, the court announced it would consider the case on its merits and set arguments for September 11, 1958. The school opening date was delayed until September 15 to allow the legal drama to play out.

In Cooper v. Aaron, the justices firmly upheld judicial supremacy over state action. The Brown decision “is the supreme law of the land,” they said. They expressed contempt for officials like Governor Faubus who waged “war against the constitution.” The war over school integration continued after the court’s ruling. Little Rock officials refused to obey court orders and closed all high schools until 1959. Finally, parents and voters who cared more about education than segregation changed the school board. The integration of Little Rock schools resumed. The court’s decision established an important precedent. But it did not end conflict over racial issues that have divided Americans since the time of slavery.

School segregation, a relic of that system, stubbornly refuses to go away. Judges can decide legal issues, but they can’t change housing patterns or cultural attitudes. Since its unanimous decision in Cooper v. Aaron, the Supreme Court has split over cases dealing with school integration. Brown is still on the books, but the question remains: when will Black children in schools across the country receive the integrated and equal education the constitution commands?

__________________________________

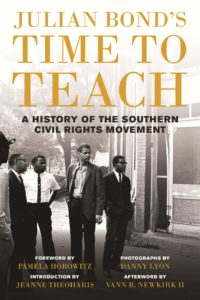

Excerpted from Julian Bond’s Time to Teach: A History of the Southern Civil Rights Moment by Horace Julian Bond, edited by Pamela Horowitz and Jeanne Theoharis. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.