Growing Up a Refugee, Confronting Shame and Sensationalism

Pajtim Statovci Finds Comfort in Storytelling

I was born in 1990 in Podujevo, Kosovo. Back then Kosovo was a part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, a country in Southeast Europe that disintegrated during the Yugoslav Wars. In 1992, after numerous demonstrations and violent confrontations between the Albanians and the Serbs, my family fled to Finland to seek asylum.

Growing up, the situation kept deteriorating, and soon bombings, military movements and assassinations were everyday news. At the age of seven I started attending a Finnish school, and even though I didn’t have any memories of life in Kosovo or any knowledge whatsoever about what was happening there, to my peers I became the face of my culture.

The media covered the stories of the oppressed Albanians, writing about the violence and the constant restlessness, about the people who were forced to leave their homes, who had lost their families and were left with nothing. I found myself confronted by questions about the world that was being torn apart by apoplectic outbreaks of cruelty and hysteria.

To my own surprise, these questions didn’t make me sad. Nor did they make me angry. Instead they made me feel ashamed, created a need to lower my head and wish for another nationality. I even remember saying to my mother that I was sick of these people behaving so badly. Why can’t they be normal, like the rest of us? I said.

After a while I started avoiding conversations that concerned language, nationality and culture, and eventually, after realizing how uncomfortable I was when my home country was brought up, I stopped speaking Albanian altogether, pretended that I’d suddenly forgotten it. My mother tongue had become a shameful secret. It no longer was a strength, an addition to my knowledge of language.

I learned that some languages are more useful than others, and I learned that it is one thing to tell someone you are French or English and another thing to say that you come from Somalia or Iraq. I learned that my Swedish peers were not immigrants. I learned that they were brothers and sisters living in the Finnish society, they were members of the ‘civilized world.’ Whereas I, an ethnic Albanian, was a member of another world, an asylum seeker, a refugee of war, poverty and discrimination.

I learned that I come from a country with a history of sorrow, pain and anguish, and because of that I was seen as less fortunate. My home country was not known for making fast cars, mobile phones or parts for airplanes, and when I told someone where I come from, instead of interest I was often met with pity.

So I studied, read story after story, and worked really hard because I needed to prove that I am more—a fluent speaker of foreign languages, a writer, a tireless reader—than what was expected from me. I’d begun to think of my nationality as a burden.

I decided to become a storyteller since it was books that brought me comfort, endless stories and points of views that had the power to see beyond a person’s background, fight against the strongest stereotypes. I was accepted into university, and in my first academic year I was sometimes asked: “How come you’re majoring in comparative literature when Finnish is your second language?” And: “Are there universities in Kosovo you could attend since Albanian is your mother tongue?”

Now my Finnish, a language I knew better than any other, was seen as a restraint, and instead of interest and appreciation for doing well in the entrance exam I faced question marks and worry. Would they ask me if I was German, I wondered. Would they see my bilingual background as an advantage if my mother tongue was Dutch or Danish instead of Albanian?

So I began writing fiction, determined to tell a different story, a story that proves that assuming anything about one’s culture or nationality based a particular point of view is the act of a narrow, lazy mind.

When I was going through my research, reading about the devastating, horrific events, the barbarous acts of violence, shocking casualty reports, and looking at pictures of bodies in mass graves, men shot dead and left to decay by the roadside, the same sensation of shame filled me, but this time it was different.

I realized that it was this, and only this, these stories and these pictures, that had forced me into a place of negation. I realized that these images were terrorizing my world and tearing my cultural heritage apart. They were regularly associating crime and violence and death with the place I came from. And it had created a need to hide it, to feel shame for it, even for my mother tongue, made me believe that by being a representative of a certain nationality I was somehow responsible for its history.

It is alarming how the same thing is happening today. It’s almost as if there are certain words being used when talking about building up walls so that certain people from certain countries will be kept out. We use phrases like “a flood of refugees,” “a never-ending stream,” and “a tsunami of incomers” when talking about immigration. Certain figures of speech, associated with natural disasters and catastrophes, are being—almost as if carefully selected—used to set the tone of how it will be allowed to speak about representatives of certain religions and cultures, their tragedies and the places they come from in the future.

By telling select stories from particular standpoints, the media often ends up being the oppressor, even though its mission is the opposite. By neglecting one of its essential responsibilities—the duty to carefully provide a responsible message that is able to cross borders far easier and travel much faster than man—the media ends up silencing a voice, stealing a life, a history, erasing a spoken language and diminishing a culture, a religion, taking a whole country off the map.

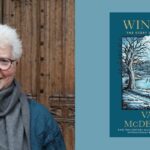

Pajtim Statovci

Pajtim Statovci (b. 1990) moved from Kosovo to Finland with his family when he was two years old. His debut novel, My Cat Yugoslavia, relates in sensitive and finely tuned prose the inner conflict and questions about one’s identity that immigration, homosexuality, and the past might stir. The novel, published in 2014, received widespread acclaim among critics and readers alike, and Statovci won the Helsingin Sanomat Literature Prize in the category ‘Best Debut’. The awarding jury praised the still only 24-year-old author’s ability to combine the dreamlike with the realistic, and give old symbols new meaning and power. At present, Pajtim Statovci studies comparative literature at the University of Helsinki, and screenwriting at Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture.