I was getting the fuck out of Raqqa.

Fleeing, maybe, but I didn’t like to think of it like that. I preferred to consider myself a traveler, engaged in picturesque sightseeing out of town. But whatever words I used, one thing was certain. After last week’s debacle, it was time to leave.

I just had to pass that last checkpoint.

I sat packed in a minibus with 19 other people, sweltering in the summer heat, 10 vehicles in line ahead of us. Beside a man-high dirt wall, two ISIS fighters guarded the checkpoint. They processed us at a fast clip. This was a small mercy, but you couldn’t credit it to kindness. ISIS was attacking dozens of rebel groups, most prominently Jabhat al-Nusra and al-Jabha al-Shamiya, and this checkpoint sat on the front line. Fighting might erupt at any moment. If it did, vehicles stuck waiting in line would just get in the way.

Our turn came. The driver collected our IDs and gave them to the fighter so that he could check our names against ISIS’s list of people they especially disliked.

Sweltering in the bus, I weighed my odds of getting through, which was my first step to reaching Turkey. If the checkpoint Brothers found a problem, they’d yank me off the bus, throw me in jail, and systematically torture me before offering me the star role in a propaganda film, which would end with me getting shot in the head. American journalists would no doubt praise it as “slickly produced.”

I stole a glance at the fighter. My nemesis.

He was Syrian, cool as day-old coffee, dressed in body armor, camouflage, a suicide belt, and two bullet bandoliers. With all the war gear, he was as massive as a marshmallow man, his head and hands sticking out like nubs from his padded body.

I put my odds of getting through at 10 percent. My enemy asked the driver where we were going. “Azaz,” the driver said, referring to a gangster town on the border with Turkey. With a look of contempt, my enemy handed back the IDs. Then he waved us past.

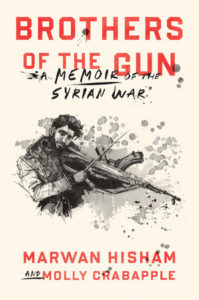

Illustration by Molly Crabapple.

Illustration by Molly Crabapple.

The checkpoint vanished behind me, and I thought of the previous four years, and how much a person, and a country, can change.

Memories always hit you hardest when you’re leaving, and the good ones are the most painful of all. I remembered my first day at the university, the weight of English books beneath my arm. The lecturer spoke a language of which I understood only little, but its tones filled me with happiness. For the first time in my life, I was studying something that I had chosen. For the first time, I had the chance to choose.

“I didn’t know what would happen, but as I passed the last checkpoint, I knew it would be a long time before I returned.”I remembered when the first protests broke out. The army had blockaded a street. Beside an armored truck, the soldiers stood 50 deep. They looked like Kalashnikov-wielding statues, impatient to shoot. Thirty feet lay between them and us. Every so often, some crazy protester tore off his shirt and came at them, bare-chested, raising his hands, screaming, “Shoot me!” They shot in the air, then at his feet. Then he would run back. Later, protesters grew more persistent, and soldiers took more accurate aim.

I remembered leaving Aleppo in 2012. Posters hung on the walls, praising Bashar, criticizing the news channels Al Jazeera and Al Arabia, and beneath them black-clad counterterrorism guys manned checkpoints all the way out of the city; the future was coming fast to Aleppo. The city was tense, edgy with imminence. I didn’t know what would happen, but as I passed the last checkpoint, I knew it would be a long time before I returned.

I remembered protesters’ blood at the base of Raqqa’s clock tower.

The base, painted in the red, black, white, and green of the revolutionary flag, its three stars staring out at us like a delusion or a dream.

The base, blotted out in black.

In my memories, I met Nael again. His quicksilver wit, his hustle, his idealism and gallantry. What was it Darwish said—oh Darwish, whom Nael often quoted—about a people who face their doom with a smile? That was you, Nael, when you swaggered up to that checkpoint. Nael of the sharp cheekbones, the twisted mouth above his fighter’s kaffiyeh. The jasmine I dropped on his grave.

Nael’s jasmine had been fresh in the days when Tareq first joined Ahrar. We had drunk tea all night on his visits home from the front, and he mocked the French and Chinese accents of the foreign fighters who had just started to join the Islamist brigades. Now it had long since rotted, and Tareq had grown into a soldier whom I respected but no longer knew. A man of certainty, who did not suffer from my moral discontent.

I remembered the days of Raqqa’s fall, of Tareq’s exile. At the time, the change had seemed so trivial to so many, but the world endowed it with a supernatural significance in retrospect. Who knows which perspective distorts more treacherously—to see history up close or from far away?

“The walls of the rooms where I had witnessed so many fights with my roommates were rubble now, useful only to create roadblocks or shelters against snipers.”History was written by the guns of Abu Mujahid and Abu Siraj and Abu Suhaib and all those other Abus from around the earth, who vandalized my uncle’s masterpiece with their existence. They whom we scammed and sneered at and served energy drinks and only occasionally feared—not that we would admit it, even to ourselves. No, they were prey to me, fodder for journalism. Nothing more.

I remembered the drones of September.

I remembered the Yazidi woman, in her red woolen shawl.

I felt, even in the minivan’s heat, the sweetness of spring air in last month’s Aleppo. My sweetheart had been white as the apocalypse, her streets deserted, her skies split by barrel bombs, her air choked with dust. Of the apartment building in which I once lived, only the rooftops and pillars remained. The walls of the rooms where I had witnessed so many fights with my roommates were rubble now, useful only to create roadblocks or shelters against snipers.

Memories stalked me that whole long road out of Raqqa. I looked back, in the direction of the Euphrates River.

During the golden age of the Abbasid Empire, poets described the Euphrates as a sea. But over the last few years, its waters had sunk lower and lower. It was almost a creek when I left, green with algae. I thought about things that were beautiful and things that were dead and faded and things that, like water, might rise again.

After four hours, the bus reached Azaz. From there, I headed west, toward Afrin.

Illustration by Molly Crabapple.

Illustration by Molly Crabapple.

__________________________________

From the book Brothers of the Gun: A Memoir of the Syrian War by Marwan Hisham and Molly Crabapple, Illustrations by Molly Crabapple. Copyrights © 2018 by the authors and illustrator. Published by One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.