Five Books Making News This Week: Families, Fetuses, and Foer

John Freeman, Ian McEwan, Here I Am, and More

The Brooklyn Book Festival, which features hundreds of authors from Margaret Atwood to Ocean Vuong, kicks off Monday night with a dance party (DJ Shiftee!) at the Bell House co-sponsored by Literary Hub, Catapult Press, Electric Literature, PEN America and Tumblr. Of special note in the week of Bookend events is “The Ever Expanding World of Literary Criticism,” a National Book Critics Circle panel at the Center for Fiction on September 15. Meryl Streep is set to star in and produce a TV series based on Nathan Hill’s The Nix. Sharon Olds wins the $100,000 Wallace Stevens award from the Academy of American Poets. The Academy’s $25,000 fellowship goes to Natasha Tretheway. Also honored: Lynn Emanuel, Mary Hickman, Ron Padgett, Stephen Sartarelli, and Donte Collins. The fall book season begins with major new novels from Ann Patchett, Ian McEwan and Jonathan Safran Foer. The new Freeman’s theme is Family, and Ross King writes about Monet’s “mad enchantment” with waterlilies.

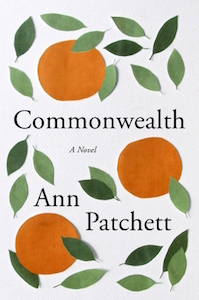

Ann Patchett, Commonwealth

Patchett, who set her PEN/Faulkner and Orange Prize award-winning Bel Canto in Peru and her latest, State of Wonder, in the Amazon, delivers a novel that covers a half century of major changes within two American families “blended” after an affair. Her elliptical and compassionate narrative finds fans.

“This is not a book one turns to for plot,” writes Janelle Brown (Los Angeles Times):

The present story lines are overshadowed by the events of the past, the book’s most contemporary scenes existing primarily as an entrée to older memories. But that is perhaps Patchett’s point: That life is a series of vignettes strung loosely together, and that there are moments from which the rest seem to hang, the points from which a family may never really recover.

Reading Commonwealth is a transporting experience, as if you’ve stepped inside Patchett’s own juice-saturated memories and are seeing scenes flash by, in all their visceral emotion. It feels like Patchett’s most intimate novel, and is without a doubt one of her best.

Alexis Burling (San Francisco Chronicle) also praises Patchett: “With Commonwealth, Patchett covers so much ground and throws in so many engrossing details about Franny, Albie et al, that it’s quite enjoyable just to kick up your feet and go along for the ride — even if it means getting disoriented once in a while. After all, isn’t that what signing on to hear a good yarn is all about? Delicious abandon?”

Ron Charles (Washington Post) concludes, “What family stories belong to us alone? Who in the family can be entrusted with the mismatched fragments of our history? Drawing us through this complex genealogy of guilt and forgiveness, Patchett finally delivers us to a place of healing that seems quietly miraculous, entirely believable.”

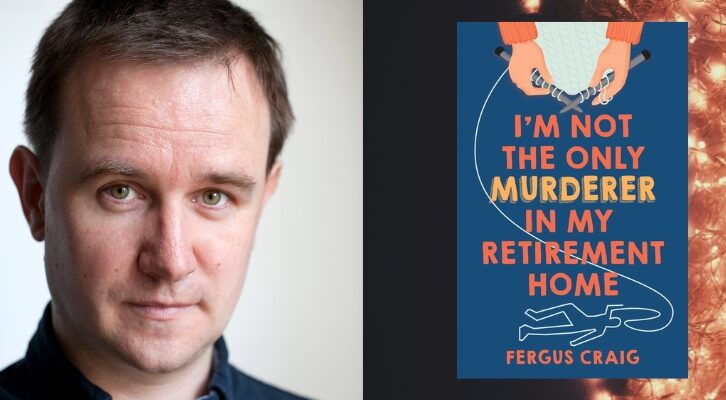

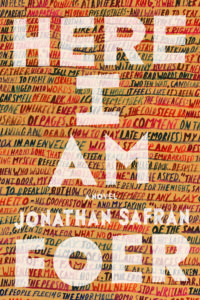

Jonathan Safran Foer, Here I Am

Foer’s first new novel in 11 years toggles between a disintegrating marriage (wife is an architect, husband a script writer for a cable television show, the oldest of their three sons is about to be bar mitzvahed) and a catastrophic earthquake that sets off chaos in the Middle East. Critics find it provocative, but not perfect.

“Here I Am,” writes Laura Miller (Slate), “worms its way closer to the squirmy kernel of Foer’s talent” than his earlier novels Everything is Illuminated and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, which, she writes, were “frantically try to please.” She concludes, “Whenever Foer isn’t trying too hard, isn’t avidly polishing away the particle of bitterness that gives his writing its particular, genuine charm—whenever, that is, that he ceases trying to charm—Here I Am becomes a novel well worth reading.”

Daniel Menaker (New York Times Book Review) concludes, “the novel as a whole supersedes its difficulties — especially in its emotional intelligence and complexity, and in certain set pieces that show a masterly sense of timing and structure and deep feeling. A young, substitute rabbi gives a eulogy for Isaac, Jacob’s grandfather, that will break your heart and then mend it…”

Michelle Dean (New Republic) is not convinced.

The publisher’s materials are at pains to point out that “Here I am” is a Biblical quotation, evidently hoping to brush off some of the autobiographical implications. It is, indeed, what Abraham says to God after God has tested him, to demonstrate his continued faith. But it’s hard to resist the reading that this is Foer serving himself up in yet another thinly fictionalized form. His characters live in a large house they love in a well-to-do area of Washington, D.C. But no one in their world seems aware of the existence of government and power nearby. Their problems are the problems of the moneyed creative class—i.e., how to derive meaning and love from a world that seems to be structured against the development of either thing. In other words, they are gentrified Brooklyn problems.

Constance Grady (Vox) gives Foer credit for ambition:

Here I Am is a big, messy, bombastic book. It’s seriously flawed — it doesn’t know how to handle its political angle; it’s self-centered; it’s navel-gazey. But it also reminds you why Foer made such a splash when he first arrived on the scene.

When it comes to sheer aesthetics, you can rely on Foer to string together some beautiful, playful sentences. And he has some careful, thoughtful things to say about marriage and family and home, and how they come together and fall apart.

Here I Am is not perfect, but damn it, it tries. It swings for the fences. It’s ambitious, and if nothing else, its ambition makes it exciting to read.

Ian McEwan, Nutshell

McEwan’s seventeenth book is narrated by a fetus who witnesses a crime from inside his mother’s womb. It’s in a sense a return to his earlier work, McEwan tells Mark Medley (Globe and Mail). “In my early stories, written in the first half of the seventies, I had very improbable narrators who stood outside the world, looking in. I had, for example, a story narrated by an ape who’s having a love affair with a woman—a novelist who’s struggling with her second novel. And it was those kinds of dissociated narrators that I felt I was returning to.” Tricky, but it works.

Michiko Kakutani (New York Times) is succinct:

With Nutshell, Ian McEwan has performed an incongruous magic trick, mashing up the premises of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” and Amy Heckerling’s 1989 movie, “Look Who’s Talking,” to create a smart, funny and utterly captivating novel.

It’s a tale told by a talking fetus who’s a kind of Hamlet in utero—a baby-to-be (or not-to-be, as the case may be), who bears witness to an affair between his mother, Trudy, and his uncle Claude. This adulterous pair are plotting to kill the baby’s father, John. Can the narrator prevent this murder—or later exact some sort of revenge?

She concludes, “Mr. McEwan writes here with such assurance and élan that the reader never for a moment questions his sleight of hand. At the same time, his unborn Hamlet’s soliloquy leaves us with a snapshot of part of London that’s as resonant as the portrait of the post-9/11 world he created in his Mrs. Dalloway-inspired novel Saturday, a snapshot of how a slice of the privileged West lives—and worries—today.”

“Humour is the name of the game here,” writes Lucy Scholes (The National). “Surely that’s the only way to read a foetus soliloquising about the delights of a good burgundy or Sancerre ‘decanted through a healthy placenta,’ ranting and railing about ‘trigger warnings,’ or describing in gut-wrenching detail his uncomfortable front row seat during the actual adultery: ‘I close my eyes, I grit my gums, I brace myself against the uterine walls. This turbulence would shake the wings off a Boeing.’… the exuberance of the prose points to a knowing twinkle in McEwan’s eye; gone is the earnestness we’ve come to associate with his more recent work.

Siddhartha Mukherjee (New York Times Book Review) begins with Abhimanyu:

Locked inside his mother’s womb—as one version of the Mahabharata story runs—Abhimanyu overhears his father, Arjuna, discussing a well-known battle strategy with his wife. It involves a military formation called the “disk”: A murderous rank of enemy soldiers forms around a warrior in a perfect spiral, and seven steps, carried out in precise sequence, can penetrate that deadly labyrinth, permitting escape. Abhimanyu listens intently — at times, the thrumming drone of his mother’s aorta next to his tiny ear is near-deafening—but as Arjuna speaks, his mother dozes off to sleep. The conversation stops. The final route of escape—the seventh step—is left unmentioned.

Ian McEwan’s compact, captivating new novel…is also about murderous spirals and lost messages between fathers and unborn sons, although it’s the father’s fate that hangs in the balance here.

John Freeman, editor, Freeman’s: Family

The focus of the second issue of the biennial anthology edited by former Granta editor (and current Lit Hub executive editor) Freeman is Family (the first was Arrivals). Heavy hitting contributors include Alexander Chee, Sandra Cisneros, Aminatta Forna, Aleksandar Hemon, Marlon James, Claire Messud, Tracy K. Smith and Claire Vaye Watkins. Critics celebrate.

“The global curiosity and urge to find the best writing that marked his time at Granta has travelled with him to Freeman’s,” writes Philip Matthews (The Press).

Dotun Akintoye (Oprah) notes, “The assembled contributors—an impressively diverse group including Marlon James, Sandra Cisneros, and Tracy K. Smith—offer fascinating takes on the ties that bind.”

“The showpiece of this issue is its longest: an essay by Mexican writer Valeria Luiselli, author of last year’s beguiling The Story of My Teeth,” writes Beejay Silcox (The Australian). “Luiselli is now based in Harlem, where she volunteers as a translator for migrant children who have crossed America’s southern border unaccompanied. In her essay, Tell Me How It Ends (an Essay in Forty Questions), an immigration questionnaire functions as the cold skeleton around which she builds something warm and desperately human….In a US political climate of wall-building xenophobia, and with the refugee crisis in Europe worsening …it has never been more important to listen to these stories of displacement, of families lost, broken and forever unmoored.”

“Each edition,” concludes Sam Cooney (The Age), “boasts a diverse and ultra-contemporary line-up, giving readers a glimpse into the viewpoints and experiences of a small handful of the world’s most accomplished (albeit conventional) literary stylists.”

Ross King, Mad Enchantment

King, who has written about the 15th-century Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi’s dome and Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, focuses on Monet’s house at Giverny and how it inspired his water lily paintings over the decades. Critics are drawn into King’s dramatic story.

Linda Simon (Newsday) writes, “The gardens of Giverny became Monet’s solace—and torment. He produced more than 300 paintings of his roses, weeping willows and, most of all, his water lilies. The artist was desperate to capture the subtle glimmers of the lily pond—‘not only the fleeting shadows and surface reflections,’ writes King, ‘but also the murky, half-hidden depths of trembling vegetation.’”

Steve Donoghue (Christian Science Monitor) focuses on the dramatic impact King derives from Monet’s “volcanic temper.”

King’s account is full of tense moments in which the painter gave way to epic fits of rage in which he sometimes turned his anger against his own canvases. He described himself as “at war with nature and time,” and Mad Enchantment captures that war with page-turning intensity.

And that intensity is considerably heightened by the most unexpected figure of them all: firebrand French politician Georges Clemenceau, the “Tiger” of the public square and, according to King, “the only person in France who could manage Monet.”

“Best of all,” concludes David Walton (Dallas Morning News), concludes, “King’s marvelous storytelling draws us back to these sublime, timeless paintings, so remote from—and yet, paradoxically, so necessary a part of—our own unquiet times.”

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.