Finding Horror (and Art) in the Gray Areas of Identity

Virginia Feito on the Terrifying Power of Identity Crises in Fiction, from Shirley Jackson to Alfred Hitchcock

The term “identity crisis” was coined by developmental psychologist Erik Erikson, who believed identity was one of mankind’s greatest conflicts. Painstakingly constructed from our experiences, values, and roles in society, identity is a whole lifetime’s work—which makes the notion of “losing” it not only heartbreaking, but scary. Indeed, throughout history horror books and films have loved to dissect, with morbid relish, the grey areas of identity; losing it, faking it, obsessing over it, or appropriating somebody else’s. These have become recurrent storylines within the genre, and are more disturbing, more real, than any supernatural monster. There’s a Shirley Jackson story in which a woman, after a visit to the dentist, forgets which of the reflections in the mirror belongs to her (The Tooth). The moment only lasts a couple of paragraphs but it’s the most terrifying thing I’ve ever read.

The doppelgänger has been used in fiction for centuries to explore the duality of human nature, and yet there are few things that inspire more dread in human beings than the possibility of an identical yet unfamiliar version of ourselves walking around in the world. In some cases, the doppelgänger derives its horror by wreaking havoc and causing innocent people to suffer the consequences of its crimes. Stephen King’s The Outsider founds a good deal of its horror on the terrifying notion of an irrevocable demolition of our reputations—particularly pertinent at a time when “cancel culture” is under recurrent debate. We all have a role in society that we are eager to preserve, if only for the comfort of familiarity.

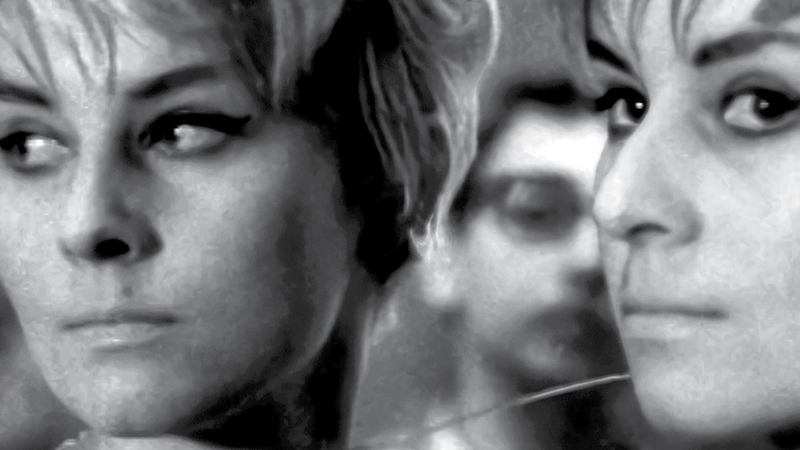

What are we clinging to when we cling to our identities? Alfred Hitchcock raises the question, and makes a fascinating choice to explore it, just thirty minutes short of the end of Vertigo, when it is revealed to the viewers that Judy Barton was impersonating Madeleine Elster all along as part of an elaborate murder scheme; that they are, in fact, the same woman. This purposeful spoiler seems counterproductive—if the viewer knows what’s up, where will the suspense and tension come from?—but it turns out to be a masterful decision, as there is no greater, more gut-wrenching horror than watching this woman give up her identity piece by piece, replacing everything that makes her “her,” from her clothes to her hairstyle to her face. James Stewart remains unapologetic though—if this woman is capable of living as refined, superior Madeleine Elster, why doesn’t she?

Patricia Highsmith’s Tom Ripley famously had no qualms about selecting a more attractive personality for himself and wearing it like an expensive suit. The funny thing about Ripley is that the reader roots for him—perhaps because we can all relate to the temptation of abandoning our real selves and inhabiting our ideal selves instead.

Some believe that one’s “real” identity consists of the fight-or-flight response that is provoked by an extreme, potentially life-threatening situation. So much of our identity, indeed, seems to depend on external circumstances—it is defined not only by ourselves but also, chillingly, by the people around us. They are the ones who can decide, or confirm, you’re not “acting like yourself” and thus fit for admission to the psychiatric ward. Shirley Jackson adeptly portrays this paradox in Louisa Please Come Home, when the short story’s titular Louisa attempts to finally return home after running away three years prior, only to be turned away by her family, who do not recognize her, and who deny her claims with such conviction that she finally agrees and wishes them luck with finding their daughter.

Human beings essentially need an identity to root them to sanity; psychopaths, who do not have them, spend their entire lives trying to mimic them. Sometimes—as in the case of serial killers who establish specific profiles for their victims—they fixate on collecting them. Through its constant instances of mistaken identity and the lack of any real character descriptions, American Psycho suggests that this hyper-capitalist society we live in, where one’s identity is so often defined by one’s material worth, churns out one clone after another, all of us adhering to the same superficial rules and lacking any meaningful connections with one another, until we steadily go crazy in isolation, forget who we are (if we even are anyone), and thus lose our grip on reality.

The line between identity and sanity was threaded long before consumer culture, however, and even in its antithesis setting: the austere, claustrophobic Victorian country mansion of The Yellow Wallpaper where, stripped of her writing, her home, company, and any familiar components that form her identity, the narrator creates an identity in the walls instead.

My debut novel Mrs. March follows a well-to-do, Upper East Side housewife whose whole identity is thrown into question when she is asked whether the repugnant, pathetic protagonist of her husband’s latest novel is based on her. Set in a world of Manhattan high society dinner parties and in an inscrutable time period that evokes classic psychological horror stories and noirs, Mrs. March tails the eponymous protagonist as she obsesses over the fictional character in her husband’s novel and steadily loses her grip on reality. Her paranoia reaches its climax when the body of a missing girl is found in an area her husband frequents on his hunting trips, and she is forced to wonder if she really knows her husband, or herself, at all.

Mrs. March is only ever referred to by her married name, even in passages recounting her childhood, as her personhood is exclusively defined by her husband and her role as his wife. She clings to this perceived identity, even though she doesn’t particularly like it, as if to a life raft, because if she isn’t the respected, elegant wife and gracious hostess she thought she was, then who the hell is she?

Her physical appearance is never described (she could be anyone), yet Mrs. March sees herself everywhere; metaphorically, both in her husband’s book and in the spiteful mouths of gossipers, but also literally, as she spots identical versions of herself at the supermarket or through the window of a neighboring building, covered in blood. Even as she is confronted with her own image, she refuses to really look at herself—again and again, Mrs. March is brought to a mirror, only to avoid her reflection, choosing instead to only see others. Her identity crisis intensifies as the book describes, in repetitive detail, the reassuring elements that constitute her life—olive bread, mint green gloves, the paintings in her apartment—while remaining ambiguous about more general, atmospheric aspects of her life, such as the time period and her surrounding community.

This contrast, between how Mrs. March sees herself and how the narrator sees her, casts her as unreliable and her identity as dubious as the narrative keeps readers at a distance. It isn’t until the very end of the book that Mrs. March’s first name—and her true identity—are revealed; but in this case, as in the rest of the horror genre, the fun lies in waiting for the inevitable, rather than the inevitable event itself.

______________________________________________

Virginia Feito’s novel Mrs. March is available now via Liveright.