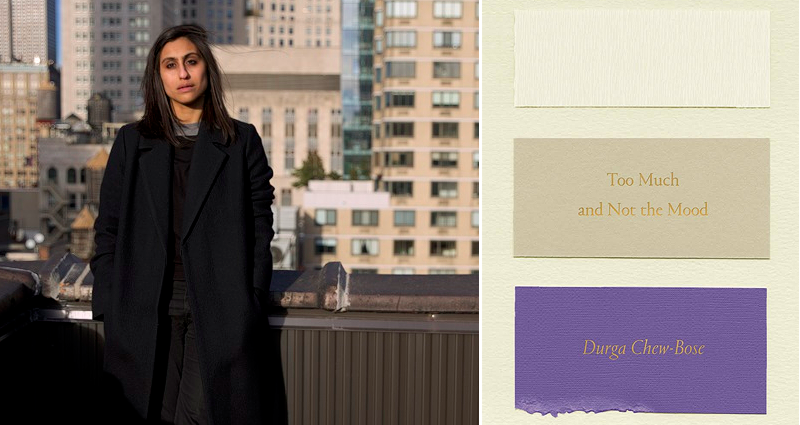

Durga Chew-Bose: “Writing Affords Me a Space to Have Contradictions”

On Riding the Subway, Shades of Lilac, and Navigating the White Gaze

I read once that every time we learn something new, neural pathways form in our brains, physical proof that we have been amazed or surprised or shocked by something. Knowing little about the the brain, I have always imagined that each of us carries inside our skulls a sprawling web, glowing like a city seen from an airplane at night, lighting up at new discoveries or re-discovery of old experiences as smells tumble into memories which build into slightly new variations of known feelings.

Durga Chew-Bose’s writing feels to me like the intricacies of this glowing brain-map laid out to shine on paper. She traverses the mazes of these pathways like a brain archeologist, returning with shining fragments of memory—her first trip to Kolkata, the sounds of onions frying in a pan, the blueness of the ocean—which she places next to, on top of, and inside of critical observations and feelings. In Too Much and Not the Mood, she is also a skilled analyst, articulating precisely concepts of daughterhood, friendship, and solitude, how the women that men construct and fetishize don’t exist in the ways they imagine, and how white peoples’ praise of her brown skin often hides their own “concealed bias.” But Chew-Bose also allows herself to meander—to explore, as we all do in our most private moments, how her mind associates the immediate and the corporeal with the otherworldly.

We spoke about the fine line between nonfiction and fiction, the playfulness of a subway commute, and about revisiting experiences with new language to describe how or why they happened.

Vrinda Jagota: The essay “D as in,” about your name, was one of the first pieces I read by you when it was originally published on BuzzFeed. I especially like when you write about keeping a running tab of “passable” Indian names. I did that too, growing up. Mine were Anita, Monica, and Lena. In my mind, these imagined women were complex, bubbly, and fully human because of their Western-sounding names. I look back on that now and think, “That was me aspiring to whiteness,” but I didn’t have that language or understanding when I was a child. In “Tan Lines,” you similarly write about feeling uncomfortable around mothers of white friends but not having words for it, being “innocent to the syntax of difference.” What is it like now to reflect on those mental negotiations you made before you had language for the experiences?

Durga Chew-Bose: Sometimes finding the language for it now might feel like a betrayal of what it was like to be young. Maybe part of being young is not having to intellectualize everything. So sometimes it feels like I’m betraying my younger self. But sometimes it also feels like I’m speaking to my younger self, saying, “You were right in feeling off.” Because how do you express feeling off as a kid? You don’t. You try to change.

I don’t really ascribe to the idea, “Write for the younger version of you who wishes this book existed.” I’m writing now with this mind. But [as] I write now, [I also keep] in mind how I was kind of late to bloom in understanding that some of these moments that were making me feel uncomfortable, or distrustful, or like an outsider were legitimate.

It’s hard also to know what an instinct is when you’re a kid because it can be really fleeting, or it can conversely happen every single day. So you either become blind to it, or you don’t really know how to itemize or declare that this moment, or this friend’s mother, or this gesture, or this word is not natural to you.

VJ: I like the way you write about your first visit to Kolkata, how you don’t remember it, but also, of course, you innately do. It’s the feeling of chiffon, the memory of jumping over a puddle, lightbulbs illuminating fruit stands, you write. My idea of India is similar—it’s a collection of feelings, a string of memories. But when I try to write about it, the words of white writers always come to mind, which are often exoticizing and oversimplifying: words like “spicy,” “sweltering heat,” and so on. I wonder how to write past that white gaze. Do you also grapple with that when you’re writing about India?

DCB: When I write about my family and my own experiences, there’s not a lot of room for the white gaze to come in because the gaze is my gaze, or rather, me trying to strain what I can from my memory of being a kid. I think I definitely have a resistance to using certain words or iconography because it makes me wonder if it’s too palatable to white people, and I would like to make them a bit uncomfortable. But even that [idea] I quickly shed because that’s dumb; I shouldn’t be trying or not trying to make people uncomfortable, I should just be writing. If what I write, white readers take to and it totally legitimizes their idea of India, or Kolkata? Fine. But I wrote that, and I put time into it, and I revisited it, and I read it out loud to myself, and I thought about its implications.

But other times I don’t think about the white gaze at all, because I think it’s so narrow. For instance, my mother is Anglo-Indian, and I can’t tell you how many people will see a picture of her and be like, “Your mother is white.” I don’t know if I have it in me to explain what being Anglo-Indian is. In my book, I talk about aunts whose names are Jennifer and Lois. And my mother’s name is Dolores. I don’t pause at any point to say, “They have these names because . . . ” My grandfather’s name is Felix and my grandmother’s name is Dulcie, and I’m sure some people reading it who are living in their little world of thinking everyone from India has these six names will be confused or will have some weird whiplash, but that’s on them.

I am writing my own experience and I never feel like I need to explain my family’s roots. I don’t want to feel like I have to slow down so that this purported white gaze can keep up with me. I’ve had to keep up with white people my whole life. I’ve had to learn about other cultures and other traditions and other ways of speaking and other names and just understand it as some kind of norm. So if I just establish mine as my norm, then that’s all I can do.

“When I write about my family and my own experiences, there’s not a lot of room for the white gaze to come in because the gaze is my gaze.”

But I definitely worry sometimes. Am I allowed to write a short story one day that takes place in Kolkata. Am I allowed to write about the smells there? Am I allowed to write about every ingredient we need to make kicheri, or will I hesitate because I don’t want to be “that writer”?

I was recently at the Alice Neel show at David Zwirner Gallery, and there was a painting there of a woman in a beautiful sari. I was drawn to it. I only took a few pictures at the show, and I took that picture and zoomed in on the details of the sari and the gold ring she was wearing because it reminded me of the bangles I wear. I wanted to send it to my father to show him the detail, but I did have something briefly stop me where I was like, “Oh, of all the paintings in this exhibit, I’m taking a picture of the woman with a long braid in a sari.”

But that stuff is hard to shake, and I wouldn’t be me if I were completely confident with my identity as well. I think part of why I took to writing as a form to express myself is because it leaves a lot of room to work through experiences on the page, as opposed to just present them as-is. Writing affords me a space to have contradictions.

I think about that stuff, but I try not to because it really stalls the writing, and it delegitimizes why I do what I want to do. It’s also letting whomever might be happier if I’m silent win. I try not to let it infiltrate too much, but I’m not saying it’s easy.

VJ: Throughout the text, you show yourself discovering and remembering things as you write. For instance, in “Some Things I Cannot Unhear” you are first unsure what color your grandmother’s sari was, but towards the end of the essay you remember that it was forest green. What motivated you to make evident this experience of epiphany and evolution through writing?

DCB: Part of what was fun about working on this book—because writing is definitely not necessarily a fun task—was that I let myself include on the page some of the “behind-the-scenes” of writing, the misremembering or second guessing. Even if it’s just a question of style, on the page there is a different rhythm when you go back on your word, or when you have to consider for an extra beat something you thought you were otherwise confident about. In that way, rhythmically questioning my memories was why I chose to include that stuff.

Also, my relationship to memory is so linked to my relationship to what isn’t real. It’s a funny thing when you’re writing about something you experience but can’t remember it exactly as it happened. Once you accept that, the non-fiction becomes fiction. And you can wade through that as much as you want to. I chose to, in certain cases, play around with what really happened, what might have happened in my head, and how my memories are vague, how that all blends together.

VJ: You also write a lot about your experiences riding the subway. What are your favorite rides?

DCB: I think it’s more a question of lighting on the subway. I weirdly don’t like riding the 4/5, because I find the lighting in there really bright and fluorescent.

Later on today I have to go uptown, and I was thinking about the quickest way to get there, and I had the thought, “Oh it’s nice—I’m going into Manhattan today.” Sometimes there’s something very playful about having a commute—obviously when it isn’t rush hour and you’re going to work. Sometimes [a subway commute] can add a certain quality to getting somewhere because it gives you a buffer time in between. I don’t step out and walk straight into where I need to be; I have to get there.

And of course, if you’re running late, then that’s not the most enjoyable. I think it also depends on where I’m going. If I’m going somewhere I’m not excited to go, the ride can feel like me stepping into all of my vulnerability and replaying every scenario that I don’t want to have. So sometimes the commute is an extension of my panic. But other times it’s nice because you’re forced to be around other people, and so much of writing is being by yourself, so you have to make room for other people, and shuffle around, and be considerate, and have strangers to look at and stories to watch unfolding in front of you.

You can be really romantic about the subway, but it’s not always romantic. It’s terrible when you’re waiting for an F train at 11:30 at night and it wont come for 35 minutes. For the most part, it’s where I do a lot of my reading.

VJ: I love when the M goes above ground.

DCB: Yes, of course! When it goes above ground, there’s nothing better. When I’m having a not-particularly-great day, I sometimes wish I was riding a train that was all above ground because something about sinking underground, or being underground for an extended period of time, can just make me feel more claustrophobic than I might already be feeling with my own thoughts.

DCB: The title of your book, Too Much and Not the Mood, is a Virginia Woolf quote. Was she an inspiration for the book as a whole as well?

VJ: Yeah, for sure. The title is from an entry in one of her diaries. On April 11, 1931, she wrote that. And I love Virginia Woolf. The Waves is one of my favorite books. I love her diaries. I take great comfort in the fact that her writer’s diary is equal parts navigating the length of the day and how surprisingly quick one might pass, but also contains just the everyday back and forth of editing a book, or the conversations you have in your head about something you’ve written, wondering if when you wake up next morning it will still have the same meaning to you.

In her diaries, she is very comfortable being insecure, and very confident and staunch, so I also admire her personality in some ways. I know she can be a bit short with people, but I also love that. I remember reading this other writer’s diary, May Sarton. She was talking about the first time she met Virginia Woolf; she was really nervous to meet her, and one quality that she really loved about Woolf was that she was a very serious woman but when she was with her friends, she would kind of tease them. I relate to that. I can be a little bit removed, or distant, or not totally accessible, but if I’m super close to you, one of my ways of showing affection is teasing.

VJ: How did you decide on the order of the essays and the cover image?

DCB: I had given my editors a temporary order based on my own feeling of what a good flow would be, but it was actually one of my editors, Maya Binyam, who recommended that the longest essay be in the front. I had originally thought “Heart Museum” should be the last essay, and she quite rightly and instinctively suggested that we shouldn’t give readers the longest thing to read at the end. She also suggested modeling [the layout] after Hilton Als’ White Girls, how his longest essay is in the front of the book. Because the essay also meanders a lot and includes a lot of themes that are in the rest of the book, we put it first.

[Regarding] the cover, they were really open at FSG with me saying what I like, palettes I’m into. I remember in the way beginning stages, before I was close to even thinking about finishing half of the first draft, I met with Rodrigo Corral, who is the head of design at FSG. I showed him these Raf Simons swatches from when he was working with an upholstery company. Their ad had swatches from the sofa, and you can see the threads. I loved how it didn’t look digital in that way. There’s texture.

There was a lot of back and forth, lots of different versions, lots of different color combinations. That was basically how it came to be. I was pretty invested in finding a cover that felt like it fit for me. I was very particular. You read a book and it’s with you for the period that you’re reading it; you have it with you on your bedside table, on your bed. It’s in front of you all the time. You want to be looking at something that’s pleasing to you.

VJ: You mentioned in the book that you have an affinity for lilac. Is that tied to the color on the cover?

DCB: There were other options that didn’t have the purple tone on the cover. I’m just psychically drawn to that color, so when I see it, I’ll always do a double take. I kind of love what it does to other colors more than anything else. It’s royal, it also seems unlikely sometimes, so maybe that’s why I like it. But what’s so great about it is that I know I just like it without much reason.

VJ: Can you tell me about your Instagram? How do you think of it in partnership with or in relation to your other work?

DCB: I don’t think about it that much. I think about it the moment that I’m using it, but it’s not really on my mind outside of when it’s open on my phone. I definitely feel like I’m someone who is drawn to the framing of things, be it language on the page, art at the museum, a shot in a movie. I think Instagram is a way for me to actively frame images. I’m not a filmmaker, and I’m not a photographer. It’s kind of a way for me to play around with what we don’t see, actually, more than with what we see. I think that’s all it is really.

I love patterns and I love when a color speaks to me, but I don’t really want to think too far beyond why. That’s why images are beautiful, because sometimes they do a lot more talking for you. There are so many words in my head all the time. I’m very much in my mind more than I am attached to my body, so I think that something that’s so based on images is really refreshing for me.