Day Three at Yalta, the Conference That Shaped the World: 'The Whole Palace Was Bugged!'

Diana Preston's Day-By-Day Account of the Historic Summit, 75 Years Later

Seventy-five years ago, in February 1945, some of the last battles of World War II were still being fought but the Allies—US President Franklin Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin—knew the defeat of Nazi Germany was not far off. Their next great challenge was to decide how to manage the peace and to do that the three leaders needed to meet face to face, as they had last done in Teheran in 1943. Under pressure from Stalin, the chosen venue was on his home territory—the Black Sea resort of Yalta on the Crimean Peninsula, recently liberated from the Nazis.

Between February 4 and 11, 1945 the “Big Three”—as the press called them—made decisions that resonate to this day. Stalin’s price for Soviet entry into the war against Japan enabled the Red Army to advance into Korea and precipitated the Korean War, leading to the continuing partition of Korea and the ongoing confrontation with the Kim dynasty today. Yalta also seeded the ground for the Cold War. Within just weeks Stalin violated protocols signed at the conference that should have guaranteed democratic freedoms for the countries of Eastern Europe, and the Iron Curtain began to descend.

This diary reveals—often in the words of those who were there—what happened on each of eight momentous days, exactly 75 years ago, as Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill not only defined a new world order but bequeathed a problematic legacy to our time. (Head here to read day one of the Yalta diaries. And here to read day two.)

*

Day Three

Tuesday, February 6, “warm, pleasant weather”

Morning: Vorontsov Palace

Churchill’s secretary Jo Sturdee writes home that she is “eating far too much … I wish I were a camel and could store some of the lovely creamy butter”—all such a contrast to the strict rationing back home in wartime Britain. But the lack of safe drinking water and copious vodka, champagne and wine are a challenge: “You have to take darned good care that you are definitely steady on your feet and can walk in a straight line.”

The UK delegation is amused by evidence that Stalin’s security staff have bugged the Vorontsov Palace. Two days after Chief of Air Staff Peter Portal remarked loudly that a large glass fish tank with plants growing inside “contained no fish,” goldfish suddenly appeared in it.

Morning: Livadia Palace

Like the UK delegation, the US delegation are learning to cope with the minimal bath and lavatory facilities. Admiral King’s quarters—the boudoir of the last Tsarina—contain the only functioning lavatory on the first floor. King likes to read while sitting on the toilet. With other senior military personnel also clamoring to use the lavatory, “a time and motion system,” as one colonel jokes, is introduced.

Later that morning: nearby port of Sebastopol

Anna Boettiger, Sarah Churchill and Averell Harriman’s daughter Kathleen drive along tortuous roads to the port of Sebastopol—“a terrible sight,” Sarah writes. “I didn’t see one house that had not been shattered.” Bedraggled Romanian prisoners of war queue for food, “something out of a bucket brought on a cart by a tired thin horse. One has seen similar queues of hopeless stunned humans on the films—but in reality, it is too terrible.”

Noon: Livadia Palace

With mounting international speculation about the conference’s location and purpose, Foreign Ministers draft a press release. The “Big Three” are meeting “in the Black Sea area” to concert plans “for completing the defeat of the common enemy.” Discussions will include “the occupation and control of Germany” and “the earliest possible establishment of a permanent international organization to maintain Peace.” No further information will be released until the conference ends.

13.00: Roosevelt’s apartments, Livadia Palace

Churchill arrives for lunch with Roosevelt. Determined that he should not exhaust her father, Anna Boettiger asks Harriman, who is attending, “to shoo the PM out at 2.45.” In fact, Roosevelt himself brings the lunch to a close at 3:00, suggesting Churchill takes a siesta before the coming plenary session. Hopkins turfs one of Roosevelt’s oldest friends and aides, General “Pa” Watson, who is ill, out of his bedroom to accommodate Churchill.

16.00: Grand Ballroom, Livadia Palace

The third plenary session opens. Churchill renews his demands for a strong France which—when US troops go home—“alone could deny rocket sites on her Channel coast and build up an army large and strong enough to contain” any German resurgence. Backtracking a little from the previous day, Roosevelt says that though the American public want their troops home quickly, the establishment of a world organization to preserve the peace might alter their attitude. Thus, he has neatly turned discussion to one of his key objectives—the establishment of the United Nations.

Secretary of State Stettinius sets out the US’s proposed voting formula for the UN Security Council which will have eleven members, of which five, including the US, UK and USSR, will be permanent members. No motion will be carried unless at least seven members support it. However, since these seven must include all five permanent members, this means each of the latter can exercise a veto on any measure it does not like.

If Poland is a matter of honor for the British it is “a matter of life and death” for the Soviet Union.

Though Roosevelt sent Stalin a note outlining these proposals two months ago, Stalin looks puzzled. Hopkins decides “That guy can’t be much interested in this peace organization.” Stettinius thinks Stalin believes “we are trying to slip something over on him.” Stalin says the proposals “are not altogether clear” and he wants to study them further, adding that “The greatest danger is conflict among ourselves.” The Soviet Union, America and Britain are currently allies, but who knows what might happen in ten years’ time? The UN arrangements must be robust enough “to secure peace for at least fifty years” and preserve the great powers’ unity.

Next comes the subject of Poland’s borders. All three are agreed that Poland’s 1939 borders should move westwards to restore to the Soviet Union some of the territory forfeited in fighting after the First World War. Poland will be compensated with German land. The Soviet Union already occupies nearly all Poland. Roosevelt says it would help him win over the Polish community in the US if the Soviet Union would offer the Poles some concessions on their proposed new eastern frontier, like leaving the city of Lvov with Poland. The Poles, he suggests, are “like the Chinese … always worried about ‘losing face.’” Stalin pounces. Which Poles does Roosevelt mean? “The real ones or the émigrés? The real Poles live in Poland.”

“All Poles,” says Roosevelt, taken aback, adding that what matters more than borders is “a permanent government for Poland.” US public opinion will not accept the Soviet-backed so-called “Lublin” group, because it only represents a small proportion of Poles. Churchill agrees that Poland’s freedom and independence matter more than borders—they are why Britain went to war in 1939, taking a terrible risk that “had nearly cost us our life.” Poland must be “mistress in her own house and captain of her own soul.” It is wrong, he argues, that at present there are two competing Polish governments—the Lublin group, now in Warsaw, and the Polish government in exile in London. At Yalta they must agree on one fair and representative government pending full and free elections.

Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, Prime Minister of the Polish Government in exile in London during most of the war. Popperfoto / Contributor.

Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, Prime Minister of the Polish Government in exile in London during most of the war. Popperfoto / Contributor.

Stalin rises to his feet and marches up and down behind his chair, gesturing theatrically. If Poland is a matter of honor for the British it is “a matter of life and death” for the Soviet Union. Twice in 30 years Poland has been the corridor through which German troops marched to attack Russia. He will make no territorial concession to Poland in the east. If the Poles want more land it must be at the expense of Germany in the west. He derides Churchill’s suggestion that they can agree a new provisional Polish government at Yalta—it must have been a slip of the tongue. How could such a thing be done without the participation of the Poles? “I am called a dictator and not a democrat, but I have enough democratic feeling to refuse to create a Polish government without the Poles being consulted.” Finally, he accuses the London Poles of orchestrating attacks by anti-Communist partisans against the Red Army in Poland. Soviet troops “should not be shot at from behind.”

Fatigued and determined to wind up the session, Roosevelt says “Poland has been a source of trouble for over 500 years.” Churchill replies, “All the more must we do what we can to put an end to these troubles.” With that the most difficult session so far ends.

That evening: Roosevelt’s apartments, Livadia Palace

An exhausted Roosevelt has a massage and takes a rest. Worried about Poland, after dinner he drafts a letter to Stalin which Harriman takes to the Vorontsov Palace to show Churchill. Shrewdly couched as an appeal for Allied unity, it tells Stalin that Roosevelt is “greatly disturbed” that the three powers cannot agree “about the political set-up in Poland … If we cannot get a meeting of minds when our armies are converging on the common enemy, how can we get an understanding on even more vital things in the future?” He suggests bringing to Yalta members of the Soviet-backed Lublin group but also “other elements of the Polish people” to discuss forming a new representative government.

That evening: Churchill’s apartments, Vorontsov Palace

Churchill and Eden discuss Poland over dinner—the reality, they agree, is “that the Red Army hold most of the country.” Harriman arrives with Roosevelt’s draft which Churchill thinks is “on the right lines but not quite stiff enough.” He suggests amendments.

Later that night: Yusupov Palace

Roosevelt’s letter to Stalin, including Churchill’s changes, arrives. Stalin’s security chief Lavrentii Beria is delighted with how things are going—“On Poland Stalin has not moved one inch.”

CHECK BACK TOMORROW FOR A DIARY OF DAY FOUR.

_______________________________________

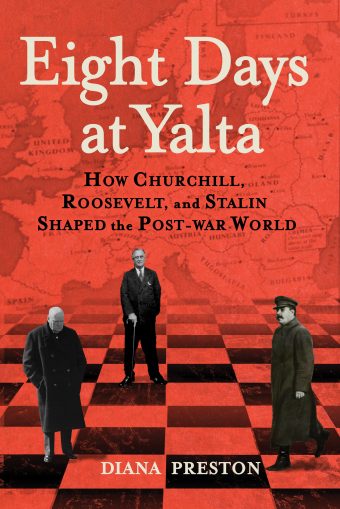

Eight Days at Yalta: How Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin Shaped the Post-War World, by Diana Preston is available now from Grove Atlantic. Featured image, left to right: Churchill’s daughter Sarah, Roosevelt’s daughter Anna, and Harriman’s daughter Kathleen at Yalta, where they were known as “The Little Three.” Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Library.

Diana Preston

Diana Preston is a prize-winning historian and the author of The Evolution of Charles Darwin, Eight Days at Yalta, A Higher Form of Killing, Lusitania: An Epic Tragedy, Before the Fallout: From Marie Curie to Hiroshima (winner of the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for Science and Technology), The Boxer Rebellion, Paradise in Chains, and A Pirate of Exquisite Mind, among other works of acclaimed narrative history. She and her husband, Michael, live in London.