Coming of Age and Questioning Traditional Rituals at a Boarding School in Kenya

Nice Leng’ete on the Teacher Who Led Her to Question the Maasai Practice of Female Genital Mutilation

My boarding school was about an hour away from Kimana by car, many hours by foot.

The first time I walked there, my grandfather came with me. The school required its students to bring a foam mattress, sheets, and a towel, and he carried my supplies for me. I carried a small bundle containing my clothes, a few pencils, and a bar of soap.

The buildings were simple: concrete blocks and stucco, metal roofs, dusty grounds. The school was clean and well kept, but it was hardly a place of ivy-covered halls and oak-paneled classrooms. But when I saw those simple structures, I smiled and stood a little straighter. The bare-bones buildings looked grand to my eyes. I was going to learn. I was going to be a real student.

My grandfather left me at the gate. “Make us proud, Nice,” he said. I thought of his kindness in welcoming me into his home. I thought of his smile when he called me twiga. I did not think of his wife at all. I was going to make him proud, I swore to myself. I nodded and smiled but did not say anything back. I knew that if I tried to speak, I would end up crying.

Our dormitory was one large room crowded with metal bunks. I found an empty one and made my bed. A few girls had already arrived and were talking by their bunks. I smiled at them. Maybe I should have been nervous about whether I could keep up with the work. Maybe I should have worried about whether I would fit in. Instead, I felt free. I knew I was out of danger, surrounded by girls who would soon be my friends. Throughout the afternoon, more girls arrived, some tense and stiff, some smiling widely. By the end of the afternoon, most of us were laughing together.

At my boarding school, the students came from many miles away. Few Maasai girls were educated past elementary school— none, as far as I knew, from my town. So even though the school was in a predominantly Maasai area, most of the girls and teachers were non-Maasai. FGM is practiced in about thirty of over forty Kenyan ethnic groups. Many groups who practice it do so at lower rates than among the Maasai. So for Kenyan women, it is hardly a universal practice. For the first time in my life, I kept company with girls who would not get the cut.

Some girls were curious, asking the Maasai girls who had been through the cut but were not yet married to show them their scars. They pulled at our towels in the showers, wanting to compare us. I held on to my towel extra tightly and tried to avoid those girls.

Even that teasing had a good side. It showed me that there was another way, that getting the cut was not the natural thing I had always been taught it was. That maybe I could find a way not to get it and still find a place in the world.

Without the long walk to and from school, without the constant labor, I had time to study. I slept better in a bed and without bruises on my body. I stopped falling asleep at my desk. I still had to work hard, and I took in laundry and earned money in the fields, but the workload was never unreasonable. I became a good student, and my teachers noticed.

As much as a person can prepare for something as terrible as female genital mutilation, the girls are ready.

I had an English teacher, Miss Caroline, who was my favorite. She was a tall, slim, light-skinned woman with beautiful long hair. She always had a smile on her face, though she was not afraid to smack our hands if we misbehaved.

She was also Kamba, one of the larger ethnic groups in Kenya.

Unlike the Maasai, the Kamba people do not practice FGM.

Miss Caroline told us that her door was always open, and since I did not have any adult women to talk to, I took her up on the offer. The first time I went to her office, I stood outside the open door. Would I be bothering her? Would I make her think less of me? I took a deep breath and, head down, walked slowly into the room.

“Is it okay to talk?” I asked.

“Always, Nice, always,” she said, smiling.

The words came out in a rush. I talked about how much I missed my sister. How I missed my grandfather. Classes were challenging at my new school, much more challenging than the ones at the day school I had attended before, and I told her I was worried that I would never catch up. I was worried, I said, that I would not make my grandfather proud.

She nodded and listened, saying a word or two to encourage me, but mostly she sat quietly.

She did not even have to offer advice. When I was done speaking, my chest felt lighter. I think I might have smiled.

Then I froze. I realized that I had been talking for almost an hour. What had I done? Was she going to judge me? Was she going to think I was weak?

“Nice,” she said, leaning toward me, “I am so glad we got to talk.

I hope you come again.”

I smiled. Of course I would.

“What would you like to do when you grow up, Nice?” she asked me one day.

That was the first time an adult had ever asked me that question.

I did not have an answer.

The school was full of working women. Many, including Miss Caroline, did not have husbands. They seemed happy. Maybe, I thought, I could do something with my life.

Did I? Could I avoid the cut? The thought excited me, but it was frightening too.

I loved our English class. The language was infuriating—why do “caught” and “cot” look nothing alike and “tough” and “dough” look so similar?—but I could lose myself in the challenge.

After class, Miss Caroline handed me books. They were dog-eared, hand-me-down books for toddlers, but to me, they were precious. As I carefully sounded out the words (or got frustrated realizing that spelling often has no relationship to the sounds that make up the words), I was discovering a new world.

“You work hard,” Miss Caroline said when I returned each book and asked for another. “Hard enough to continue your education. Think about it.”

I did think. Could I finish boarding school? Could I go to college?

After class one day, she asked me to stay. “Nice,” she said, “we need to talk.”

She didn’t have her usual wide smile. Had I done something wrong? Had I failed a test?

“I have taught Maasai girls before,” she said.

I nodded.

“Not one has finished school. They go home. They get circumcised. Maybe they come back for a month or two, but they always leave. I try to talk to them while they are still young. I let them know there is another way. Before they drop out and start having babies. Is that what you want, Nice?”

Of course not. I wanted to stay in school.

I was younger than most girls who got the cut. Usually, a Maasai woman watches her daughter. When she starts to grow tall, when her breasts start to bud, she knows it is time for the cut. The mother goes to the girl’s father, and he arranges the ceremony.

The ceremony usually happens just before a girl enters puberty. The girls are still young, but they have weeks with their mothers, preparing for what is going to happen, gathering strength from her stories. As much as a person can prepare for something as terrible as female genital mutilation, the girls are ready.

No one had spoken to Soila and me about getting the cut, so I thought I had time. But eventually, it would happen.

“I have to get the cut,” I said quietly.

“Does that mean dropping out of school? Think about it.”

I knew that my parents had wanted me to get the cut, but I also knew they valued education. They would never want me to drop out of school. Did one thing make the other impossible, or was that an outdated tradition? I had never pieced it together, but maybe my teacher was right.

“Do you really have to get the cut?” she asked me.

Did I? Could I avoid the cut? The thought excited me, but it was frightening too. Shouldn’t I want to marry and have children? Was there something wrong with me?

“I have time,” I said. “The cut is years away.”

“Whatever you decide,” she said, “you can always come to me.”

__________________________________________

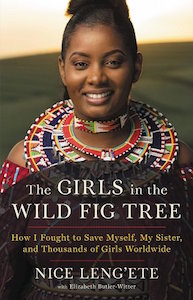

Excerpted from THE GIRLS IN THE WILD FIG TREE by Nice Leng’ete. Copyright © 2021 by Nice Leng’ete. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company. All rights reserved.

Nice Leng'ete

Kenyan human rights activist Nice Leng’ete is from Kimana, Kenya. When she was eight years old, she defied cultural convention and fled from female genital cutting. Nice managed to become the first woman in Masai history to be bestowed with the Black Talking Stick, known as “esiere.” The stick is a symbol of leadership and allows Nice to engage in conversations with men and the elders, a right usually denied to Masai girls. Nice advocates to end female genital mutilation and replace it with alternative rites of passage. Through her work with Amref Health Africa, she has helped save an estimated 15,000 girls from the cut and forced childhood marriages. Nice created Nice Place Foundation, a leadership training academy and rescue centre. The Foundation is a sanctuary for girls at risk for circumcision and early marriage, a place for them to realize their full potential.