Christina Lamb on the Remarkable Life and Boundless Determination of War Correspondent Virginia Cowles

“Cowles’s encounters with all the key players have led some to describe her as the Forrest Gump of journalism.”

One of my favorite Virginia Cowles anecdotes concerns Lloyd George reading her article on the Spanish Civil War in the Sunday Times and being so impressed that he quoted it in Parliament, before asking Winston Churchill’s son Randolph to bring the author to lunch in the country. The piece had no byline, and when this glamorous young American stepped out of the car, he was blindsided.

“The old man regarded me with surprise that almost bordered on resentment,” Cowles wrote afterwards. “I suppose it was a nasty shock to find that the eminent authority he had quoted was just a green young woman.”

In the end he recovered, showing her his chickens, pigs and cows—“sloshing through the fields like an ancient prophet with his green cloak and long white hair blowing in the wind”—and sending her home with a jar of honey and a dozen apples.

This is classic Cowles: self-deprecatory, while revealing her impressive list of contacts, bordering on name-dropping, as well as possessing an eye for the telling detail.

As a female war correspondent who grew up devouring the work of trailblazers such as Martha Gellhorn, Lee Miller and Clare Hollingworth, whose reporting of the Second World War paved the way for my generation, I have to admit it took a long while for their contemporary, Virginia Cowles, to come onto my radar, even though she had worked for my own paper. Reading this book after meeting her daughter, Harriet, I was blown away. First, by the image of Cowles as a twenty-six-year-old debutante from Boston arriving at the Spanish Civil War in hat, tailored suit, fur jacket and heels, with a typewriter and a suitcase containing three wool dresses. “I had no qualifications as a war correspondent except curiosity,” she writes.

Curiosity is, of course, important, as is determination, which she had in spades—she would go on to be one of the only reporters to cover the Civil War from both sides. What Cowles also had, as this book reveals, was an astonishing ability to paint a scene and transport the reader there. It’s hard to think of a more compelling account of the Nuremberg rallies than her description of “the huge burning urns at the top of the stadium, their orange flames leaping into the blackness… the steady beat of drums that sounded like the distant throb of tom-toms… a shimmering sea of swastikas,” and her own growing claustrophobia as she watches Hitler working people up into a frenzy of delirium.

Then there is the fact that she seemed to know everyone. A few days after that rally, she attends a tea party for Hitler. There, she witnesses his bizarre friendship with twenty-four-year-old Unity Mitford, who tells her over supper about Hitler’s love for gossip and his impersonations of Goering, Goebbels and Mussolini, claiming that if he was not Führer, he could have made a fortune in vaudeville. Breezily, Unity assures her he won’t go to war. “The Führer doesn’t want his new buildings bombed,” she says.

On returning angry from a doom-laden Czechoslovakia following the September 1938 Munich Conference, in which Britain and France allowed Germany to annex the country’s Sudetenland borderlands, believing this would avoid a major war, she is invited to dinner with one of its architects, Lord Chamberlain. Hitler is “beginning to lose his power,” he assures her.

Cowles’s encounters with all the key players have led some to describe her as the Forrest Gump of journalism. Another Sunday lunch is with Winston Churchill, who, after searching his pond for his lost goldfish, shows her his paintings and launches a diatribe against Chamberlain for failing to realize the threat Britain is facing. Then there is a series of lords and aristocrats who turn up conveniently with planes just when she needs them. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised: after all, Cowles had started off as a “society girl columnist” in New York, writing in Harper’s Bazaar about fashion, debs and the death of romance.

Indeed, her own story was as remarkable as the subjects she covered. It was the tragic premature death of her mother, Florence, from appendicitis in 1932, when Cowles was just twenty-two, that set her off on the road to foreign reporting. Florence had left an insurance policy worth $2,000, which Cowles persuaded her sister they should spend on travelling the world, in honor of their mother’s memory.

She pitched the idea of a travel column to Hearst Magazines, and over the next year wrote a series of pieces, stretching from Tokyo to Rome, where, of course, she gets an interview with Mussolini, just days after he has launched his invasion of Abyssinia. So nervous is she that she can’t eat lunch. “My knowledge of foreign affairs was negligible… I hadn’t the faintest idea how one went about an interview.” She needn’t have worried. When she enters the medieval Palazzo Venezia, guarded by Blackshirts greeting her with the Fascist salute, Il Duce lectures her about Italy’s right to have an empire.

She soon gets a crash course in foreign affairs and front-line journalism after persuading her editors to let her head to Spain, where volunteer soldiers were flocking from around the world to join the fight against Franco’s Fascist forces. Her first time under fire, while walking along Madrid’s Gran Via, captures the war exquisitely: “I heard a noise like the sound of cloth ripping… gentle at first, then it grew into a hiss; there was a split second of silence, followed by a bang as a shell hurtled into the white stone telephone building at the end of the street. Bricks and timber crashed to the ground and dust rose up in a billow… Everyone started running, scattering into vestibules and doorways, like pieces of paper blown by a sudden gust of wind.”

Though she may not have had the righteous anger of Gellhorn, she clearly cared, and like her compatriot she focused on the human cost of conflict.Most wars have their great journalist hotels, and in Madrid it was the Hotel Florida, which she memorably describes as peopled by “idealists and mercenaries; scoundrels and martyrs; adventurers and embusqués; fanatics, traitors and plain down-and-outs. They were like an odd assortment of beads strung together on a common thread of war.” Among the resident correspondents were Tom Delmer of the Daily Express, whose room became a gathering point, Beethoven’s Fifth blaring from his gramophone to drown out the artillery, and Ernest Hemingway, who would hold court in his second-floor room, with a young American bull-fighter as his sidekick. Cowles sounds unimpressed, describing him in his “filthy brown trousers and torn blue shirt.”

By all accounts it was mutual, Hemingway regarding this ingénue, with her gold bracelets and high heels, with disdain. Even so, they go for lunch, running into “a fastidious-looking man dressed from head to toe in dove grey… [with] bright marble-brown eyes” who turns out to be the grand executioner of Madrid. He joins them for a carafe of wine, and as they leave, Hemingway warns her, “Now remember, he’s mine,” later quoting him in a play.

She goes window-shopping with Hemingway’s lover, her fellow American Martha Gellhorn, staring at furs and perfumes, after which they drink afternoon cocktails in the Miami bar. I love her description of how, beneath the camaraderie and drinking, the correspondents “studied each other like crows.” Cowles was regarded as particularly suspect, because unlike most, who were partisan, sympathizing with either the Republicans or the Communists, she reported from both sides.

Though she may not have had the righteous anger of Gellhorn, she clearly cared, and like her compatriot she focused on the human cost of conflict. She quickly showed an ability to charm information from anyone and a journalist’s luck to be in the right place at the right time. At one point she gets lost driving out to one of the fronts where the International Brigades are fighting and finds herself at the divisional headquarters for the Russians who are training the Republicans, which was supposed to be secret. The Russian general is hostile but clearly captivated, sending his car to Madrid to bring her back and plying her with champagne and wild strawberries, as well as the principles of Marxism. He sends her off with a red rose.

If today there are almost as many women as men reporting from war zones, it is thanks to women like Cowles, who showed what is possible.After Spain, Cowles would jump at the sound of a car backfiring or a vacuum cleaner, but it didn’t put her off. Instead, she goes back and forth through a Europe on the verge of war, the lights going out in one country after another. She wears her courage lightly, yet takes incredible risks: to cover the destruction of Poland she zig-zags across the Channel in a boat for fourteen hours to escape the German U-boats. Eventually, she makes it to Romania, where she runs into her friend Lord Forbes, who in his own plane flies her to the border, where she finds a hotel full of dazed Polish refugees fleeing the German tanks and bombs. Among them are three children sitting on suitcases, waiting for parents who will never come.

From there she heads to Finland for the little-remembered Winter War. After their country was invaded by the Soviet Union in November 1939, the Finns stunned everyone with their bravery, small numbers of soldiers on skis “sliding like ghosts through the woods” and beating back the initial offensive. After female correspondents are blocked from the front, following an allegation of sexual harassment, she works her contacts and manages to get to the remote city of Rovaniemi, near the Arctic Circle, this time clad more adequately. She is taken to a spot where a few weeks previously the Finns had annihilated two Russian divisions. It is “the most ghastly spectacle I have ever seen,” four miles of roads and forests strewn with the bodies of men and horses, some “frozen as hard as petrified wood.” It was, however, all for nothing, the lack of international support forcing the Finns into a peace agreement that ceded more than 10 percent of their territory.

By June 1940, the German forces were moving on Paris. Desperate to be there for what she imagines will be a protracted French defense of their capital, she flies to Tours and takes what turns out to be the last train to Paris. She arrives to find everyone is leaving. Somehow she manages to find a taxi and gives a lift to a girl who turns out to be a prostitute, but discovers that the hotels are all closed and her friends all gone.

Eventually, she hooks up with Tom Healy from the Daily Mirror, who has a sports car, and together they drive along the Seine and south out of the city. They are met by astonishing scenes of “noise and confusion, of the thick smell of petrol, of the scraping of automobile gears, of shouts, wails, curses, tears… Anything that had four wheels and an engine was pressed into service, no matter what the state of decrepitude; there were taxi-cabs, ice-trucks, bakery vans, perfume wagons, sports roadsters and Paris buses, all of them packed with human beings. I even saw a hearse loaded with children.”

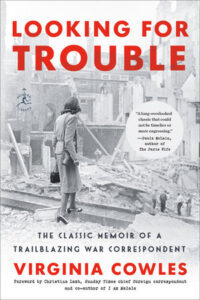

She ends up back in London, reporting on the Blitz and the Battle of Britain, writing from Dover: “You knew the fate of civilization was being decided fifteen thousand feet above your head in a world of sun, wind and sky.” She moved out of town to write Looking for Trouble, ostensibly a memoir of her journalistic exploits, but equally an exhortation for her own country to join the war.

Always fascinated by Britain, she would make it her home, and after the war married journalist and MP Aidan Crawley, with whom she had three children. She went on to write a play with Martha Gellhorn about women war reporters, as well as twelve other books on some of her rich acquaintances, such as the Astors and the Rothschilds, and a number of historical biographies.

If today there are almost as many women as men reporting from war zones, it is thanks to women like Cowles, who showed what is possible. It’s a mystery to me that she doesn’t receive the same recognition as Gellhorn.

Looking for Trouble was a bestseller when it was published in 1941, and I hope that its re-release will introduce her to a whole new generation.

____________________________________

From the foreword to Looking for Trouble by Virginia Cowles, introduction by Christina Lamb, published by Modern Library. Foreword copyright © 2022 by Christina Lamb.