Brooklyn's Earliest, Secret Enclaves of Queer Life

From Whitman to the Free Black Community of Weeksville

By the mid-1800s, Brooklyn was one of the leading manufacturers in the country for a wide range of products, from sugar, to rope, to white lead, to whiskey.

This new industrial waterfront created the conditions that allowed queer lives to flourish in Brooklyn. As America transitioned away from a primarily farming economy, the extended family—once the main economic unit in the country— began to lose importance. New urban jobs allowed (some) people in Brooklyn to carve out separate space for themselves, far from their parents or anyone who knew them. Victorian culture mandated strict separations between men and women, meaning that most of these jobs were either all-male or all-female. Huge numbers of immigrants, mostly unaccompanied men, came to New York to meet this demand for laborers, creating large working-class bachelor subcultures where heterosexual sex (outside of prostitution) could be hard to find. The trading routes that created these jobs didn’t just move goods, however; they also moved people and ideas—meaning that the average Brooklyn laborer had much greater exposure to other cultures (and their sexual mores) than did most other Americans. Many of these new Brooklyn residents were transient, living in the city only seasonally or for a few years at a time, enabling them to settle in these raucous neighborhoods with relative anonymity. Finally, since shipping and manufacturing were dirty endeavors, waterfront neighborhoods were often undesirable, inexpensive, and only lightly policed. One of the few drawbacks to Brooklyn cited by Mayor Hall in 1855 was that its police lacked the “qualifications and fitness for office.” Thus, Brooklyn’s waterfront offered the density, privacy, diversity, and economic possibility that would allow queer people to find one another in ever-increasing numbers (though these freedoms would not be enjoyed equally by all queer people). The waterfront was no monolith, however, and different parts of it offered different opportunities, to different communities, in different eras. But by the time Walt Whitman published Leaves of Grass, the areas that offered the most support to the earliest queer communities in Brooklyn were already established neighborhoods drawing new residents from around the world.

A visitor to Brooklyn in 1855 would step of the ferry onto Old Fulton Street, which roughly bisected the city. To the east was low-lying Vinegar Hill, a working-class, dockside neighborhood with a large Irish population. The area was a warren of poorly constructed, tightly packed row houses and dirty businesses, filled with the sharp smells of varnish being manufactured and iron being smelted. Bootlegging was a major business in Vinegar Hill, from small-scale home distilleries making poteen, or Irish moonshine, to industrial-size whiskey and rum operations. These illegal establishments were so prominent that when the federal government tried to clamp down on them for tax purposes in 1870, it had to flood the neighborhood with more than two thousand soldiers, in a series of pitched battles known as the Whiskey Wars.

Vinegar Hill was bordered to the south by Sands Street, an important thoroughfare that connected Old Fulton Street with the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which sat on the western edge of Vinegar Hill. The yard was the city’s most important military base and the largest navy yard in the country, a sprawling complex that was home to innumerable sailors. Inaugurated in 1801 by President John Adams, the yard was a center for early American shipbuilding, military education, and technological innovation. In 1815, the first steam-powered warship, the USS Fulton, was built here, and the Naval Lyceum (the precursor to the US Naval Academy) was founded here in 1833. By Whitman’s time, some six thousand men were employed in the Navy Yard’s nearly two-hundred-acre campus.

If a visitor continued east, a few miles farther out was Weeksville, a small town that was the only majority-black community in Brooklyn. By all accounts, Weeksville was a semirural enclave of “steep hills, deep valleys, and woodlands,” which was about ten minutes from the ferry via the Long Island Rail Road. Founded in 1838, by 1855 Weeksville had over five hundred residents (about 20 percent of the entire black population of Brooklyn at the time). It served as “the center of organized recreational activities for African-Americans from the entire region,” according to Judith Wellman, author of Brooklyn’s Promised Land: The Free Black Community of Weeksville, New York. Weeksville was “one of the two largest independent free Black communities in the United States,” a place where “people generally lived in safety, supported themselves financially, educated their children . . . and set up their own churches.” As one of the few majority-black areas in all of New York City, it served as an incubator for black political and religious organizing and a needed refuge in times of racial unrest and antiblack rioting. After a visitor passed Weeksville, the rest of eastern Brooklyn was lightly settled farmland, still crisscrossed with pastoral streams and woods, until one reached the newly incorporated town of Bushwick (formerly the Dutch town Boswjick).

If, on the other hand, a visitor disembarked from the ferry and followed Old Fulton Street to the south, they would find the land quickly rising beneath them to create high bluffs with panoramic Manhattan views. Just a few blocks into town they would encounter the Rome brothers’ print shop, one of the bustling businesses where the working waterfront edged into the more residential neighborhood of Brooklyn Heights. A few blocks farther south, wealthy families were already building the Greek Revival–style town houses that earned the Heights the label “America’s first suburb.” The area on the other side of Old Fulton Street, opposite Brooklyn Heights, would eventually be downtown Brooklyn, the city’s civic center.

For as long as these waterfront areas were economically successful (or until about the early 1950s), they enabled working-class people to create enclaves of queer life.

Farther south still, the city gave way to the industrial basin of Red Hook and the Gowanus Creek, an as-of-yet-unimportant inlet of the New York City harbor. Nearby were the gentle hills, streams, and farmland that would one day be the neighborhoods of Park Slope and Sunset Park. Finally, a long carriage ride south from Fulton Ferry would bring you to the oceanfront resorts of Coney Island, which was primarily an escape for the middle class and the wealthy. Here, hotels dotted the sandy ocean shores, giving the impression of a distant seaside holiday just a few miles from the bustle of downtown Brooklyn.

For as long as these waterfront areas were economically successful (or until about the early 1950s), they enabled working-class people to create enclaves of queer life. These groupings were often small, sub rosa, isolated, and temporary, but they formed the nucleus for the later emergence of what we would recognize as gay communities. In the queer history of these areas, five waterfront jobs reoccur again and again: sailor, artist, sex worker, entertainer, and female factory worker. Each of these jobs had particular conditions that made them more available or desirable to queer people. Sailors have always been a symbol of escape from small towns, and their long voyages, marked by single-sex isolation and exposure to different cultures around the world, provided great opportunity for sexual and gender experimentation. Artists were often given leeway to be “eccentric,” and the Brooklyn waterfront drew them with its cheap rents (and—to be honest— with its cheap sailors). Sex workers (male, female, and transgender) had ready clients, and few observers, in the dockside alleys and waterfront brothels of Vinegar Hill and Red Hook. Freaks and entertainers, particularly those who were gender nonconforming, found lucrative (if often exploitative) work in the vaudeville theaters of downtown Brooklyn and the sideshows of Coney Island. Finally, in the lead-up to World War II, female factory workers broke gender stereotypes and provided lesbians with previously unimaginable freedoms.

Given the prevalence of these jobs in mid-nineteenth-century Brooklyn, it’s unlikely that Walt Whitman was the first person to develop a queer community there. However, unlike those in the other jobs listed above, artists are often given a greater level of respect—and place in our cultural memory—than their incomes would otherwise generally afford them. Also, at a time when few people were inclined or encouraged to record their innermost thoughts, artists such as Whitman were pushed to do so. Additionally, your average artist’s behavior was (somewhat) less policed than that of your average businessman, who had both customers and coworkers to worry about. In other words, artists had a slightly better chance of being able to live a queer life, a slightly better chance of recording that life, and a slightly better chance of having that record preserved. For all of these reasons, Whitman provides a good access point to the beginnings of queer life in Brooklyn.

One of the great things about Whitman is the tantalizing hints he left behind pointing to the existence of a subculture of working-class white men who loved other men. Many of these were laborers that he met while walking along the docks, or taking the ferry, or going for a bracing swim in the ocean. In his daybook, Whitman kept lists of these men, mostly single-line entries commenting on their looks, personalities, and family relationships. A typical snippet from one such catalog, written around the time of Leaves of Grass, reads:

Gus White (25) at Ferry with skeleton boat with Walt Baulsir—(5 ft 9 round—well built)

Timothy Meighan (30) Irish, oranges, Fulton & Concord James Dalton (Engine-Williamsburgh)

Charley Fisher (26) 5th av. (hurt, diseased, deprived)

Ike (5th av.) 28—fat, drinks, rode “Fashion” in the great race Jack (4th av) tall slender, had the French pox [syphilis]

This particular list goes on for over fifteen pages, with almost no women included (and those that are mentioned are never physically described). It’s impossible to know how many of these men were receptive to advances Whitman made, but some of the entries certainly suggest they were, such as this one: “David Wilson night of Oct 11, ’62, walking up from Middagh—slept with me— works in a blacksmith shop in Navy Yard.”

Foremost among the “new experiences” that Whitman would chaunt and yawp into the American literary canon was the urban life of a man who loved other men.

These were the “young men and the illiterate” whom Whitman was beloved by. They embodied his twin virtues of health and manly comradeship. Leaves of Grass was inspired by them, written for them, and often talked directly about them. Or as Whitman put it in “Song of Myself”:

The young mechanic is closest to me, he knows me well,

The woodman that takes his axe and jug with him shall take me with him all day, The farm-boy ploughing in the field feels good at the sound of my voice,

In vessels that sail my words sail, I go with fishermen and seamen and love them.

That love was not just platonic. Foremost among the “new experiences” that Whitman would chaunt and yawp into the American literary canon was the urban life of a man who loved other men, and who was able to bring together those similarly inclined. Men loving men was not something new, as Whitman was well aware from his studies in ancient Greek. But the idea that these men constituted a specific type of person, that they could define themselves by this love and carve out space to gather together as lovers of other men—what we would today call the idea of “being gay”—didn’t yet exist in Whitman’s world. The word homosexual wouldn’t even be coined until 1868.

Leaves of Grass was written at the height of the Victorian era, which lasted from approximately 1840 to 1900. Socially, this was a relatively conservative time, but one that saw huge advances in industry and urbanization. During his life, Whitman witnessed the invention of everything from the telephone, to the photograph, to the flushing indoor toilet, to ice cream. Advances in farming, manufacturing, communication, and transportation enabled a vast population flux into cities around the country. In 1840, barely 10 percent of Americans lived in urban places; by 1900 that number had skyrocketed to 40 percent.

According to Victorian morality, women and men inhabited complementary but separate worlds. Men were rational, active, and in the public eye; women were emotional, passive, and limited to the domestic sphere of family and home. Proper women were asexual and acted as a limiting force on the “animal instincts” of men. White Victorians saw all black men and women as inherently lesser; although New York State had abolished slavery by 1855, it was still the law of the land in many places. And even in free states such as New York, black people lived under tremendous constraints (legal and extralegal) on whom they could love, what jobs they could have, and where they could live. When Leaves of Grass was first printed, New York City’s entire black population was around twelve thousand people. Few whites—even those who opposed slavery, such as Whitman—believed in true racial equality.

Due to these divisions, New York was “an intensely homosocial city,” according to the epic city history Gotham—a place where white men “clubbed, ate, drank, rioted, whored, paraded, and politicked together, clustered together in boardinghouses and boards of directors, [and] even slept together.” Aside from time with your own family, interactions between men and women were limited (particularly among the middle and upper classes). People of color lived mostly in small, segregated, and remote neighborhoods such as Weeksville, far from the economic and social centers of town. For Whitman, this meant that he lived in rooming houses that were full of white men; worked in print shops and newsrooms that were entirely stafed by white men; ate lunch in cheap oyster houses where the majority of patrons were white men; and in the evenings did his drinking and reveling in saloons that rarely admitted women or people of color.

It almost goes without saying that in a world so divided by sex (the identity), that sex (the act) was treated as a dangerous mystery. Sex education was mostly limited to what a child might observe among livestock or glean from older children (as it still is in many places today). Although Victorians are often remembered solely as prudes, they spent huge amounts of time considering and classifying kinds of sex. Sexual attraction to a person of the same sex was considered a disorder of gender, closer to what we today think of as “being transgender” than “being gay.” Sexual acts between members of the same sex were stigmatized and lumped together with other nonprocreative forms of sex under the name sodomy, which could include anything from masturbation, to bestiality, to hetero or homosexual oral sex. Legally, however, sodomy charges (sometimes called the crime against nature) were primarily used in cases of sexual assault, and not against consensual sex acts. At the time of the 1880 census, only sixty-three people were imprisoned on sodomy charges in the entire country, and only five of those in New York. The idea that people had a fixed, inborn set of sexual desires that were permanent and could be used to classify humanity into groups was only just emerging among theorists in Europe. There was little agreed-upon language to even discuss those feelings.

Leaves of Grass was not only a proclamation, it was an invitation: a love letter set afloat in the world to see who understood it and answered its call.

As Ralph Waldo Emerson pointed out in his essay, the job of the poet is that of language-maker, the person who documents and names the new experiences of the times. What makes Whitman so memorable isn’t his private desires, but his realization that those desires were shared by others, and his attempt to create or memorialize words, rituals, and experiences that these men shared—something he certainly could not have done in isolation. In Leaves of Grass, Whitman called these men his “comrades” or “camerados.” Their affection for one another he dubbed “adhesiveness.” To symbolize that love, he chose the simple calamus plant, a sturdy river reed with long vertical leaves and a protruding, phallic flower cone. Whitman wrote forty-five “Calamus poems” celebrating the love between men. He explicitly urged others to use the plant as a queer love token in Calamus #4, writing:

And here what I now draw from the water, wading in the pond-side,

(O here I last saw him that tenderly loves me—and returns again, never to separate from me,

And this, O this shall henceforth be the token of comrades—this calamus-root shall,

Interchange it, youths, with each other! Let none render it back!)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

But what I drew from the water by the pond-side, that I reserve,

I will give of it—but only to them that love, as I myself am capable of loving.

Why did Whitman choose the calamus as his gift to “them that love, as I myself am capable of loving”? Calamus was wild in Brooklyn, appearing in the very places where Whitman met his camerados. It grew on the banks of the streams where young farmers brought their livestock to drink; it dotted the marshy coast where sailors hunted for duck in between stints at sea; and it lined the secluded watering holes where salt-crusted stevedores went to wash of the day’s labor. Its phallic shape was suggestive, but so were ears of corn, were it just a matter of form. But the calamus had an added bonus: its name was an allusion to the ancient Greek myth of a pair of young male lovers, Kalamos and Karpos, who died during a swimming competition. Whitman’s Calamus poems comprise some of his most sensual and personal poetry. Over the next hundred years, this inclination to find “them that love, as I myself am capable of loving,” was a consistent hallmark of early queer pioneers.

However, cruising the waterfront wasn’t the only way that Whitman met other men. Leaves of Grass was not only a proclamation, it was an invitation: a love letter set afloat in the world to see who understood it and answered its call. The third poem in the book—“In Cabin’d Ships at Sea”—explicitly says this in its last stanza:

Then falter not, O book! Fulfil your destiny! You, not a reminiscence of the land alone,

You too, as a lone bark, cleaving the ether—purpos’d I know not whither—yet ever full of faith,

Consort to every ship that sails—sail you!

Bear forth to them, folded, my love—(Dear mariners! For you I fold it here, in every leaf;)

Speed on, my Book! Spread your white sails, my little bark, athwart the imperious waves!

Chant on—sail on—bear o’er the boundless blue, from me, to every shore, This song for mariners and all their ships.

The ability to gather people to him with his words was one of the other qualities that Emerson enumerated a genius poet would possess, writing that “by truth and by his art . . . [he] will draw all men sooner or later.” This was certainly true for Whitman. In his lifetime, men such as Oscar Wilde and Edward Carpenter (an early English proponent of gay rights) flocked to Whitman’s door, asking questions about the poet’s sexuality, which he was loath to answer. Many later queer artists would be drawn to Brooklyn because of the city’s association with Whitman. Hart Crane, the 1920s poet whose foremost muse was the Brooklyn Bridge, addressed Whitman and his legacy of “adhesiveness” directly in his poem “Cape Hatteras,” writing, “O Walt!—Ascensions of thee hover in me now / Thou bringest tally, and a pact, new bound / Of living brotherhood!”

__________________________________

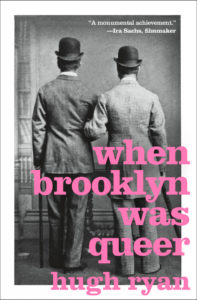

From When Brooklyn Was Queer by Hugh Ryan. Used with permission of St. Martin’s Press. Copyright © 2019 by Hugh Ryan.

Hugh Ryan

Hugh Ryan is a writer and curator, and most recently, the author of The Women's House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison, which won the Israel Fishman Stonewall Book Award from American Library Association. His first book, When Brooklyn Was Queer, won a 2020 New York City Book Award, was a New York Times Editors' Choice in 2019, and was a finalist for the Randy Shilts and Lambda Literary Awards. He was honored with the 2020 Allan Berube Prize from the American Historical Association.