Indelible performances like Bob Dylan’s at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965 and Jimi Hendrix’s at the close of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair in 1969 shattered all previous conceptions of what rock and roll could be and opened the door to new possibilities. Simultaneously iconoclastic and iconic, such moments have seared into collective memory, changed musical history, and reverberated across society, inspiring everything from fashion to calls for political action. These defining, pivotal moments make manifest rock’s potency as one of the most influential artistic movements of the twentieth century.

The instruments associated with these events—like Dylan’s and Hendrix’s Fender Stratocasters—endure as tangible evidence of these iconic yet ephemeral moments. Instruments are designed to create a sound, of course—they are the building blocks that make the music possible—but they also convey meaning. The fusion of the instrument, the musician, and the moment: that is the explosive critical mass of rock and roll. It is why singular performances and the instruments used to create them become mythical, imbued with extramusical significance. This is, after all, a musical form in which the onstage, theatrical destruction of instruments—from Pete Townshend to Kurt Cobain—is a recurrent statement of the music’s insurgent impulses. It is a form of music in revolution against itself, the explosive noise of destruction in rebellion against the inevitable rules and structure of artistic creation. That tension is central to rock and roll, and it epitomizes the role of instruments in the music.

Prince performing with his “Love Symbol” guitar during the Super Bowl XLI halftime show at Dolphin Stadium, Miami, February 4, 2007.

Prince performing with his “Love Symbol” guitar during the Super Bowl XLI halftime show at Dolphin Stadium, Miami, February 4, 2007.

The simultaneous valorization of an instrument and offhand dismissal of its importance is evident in the case of Woody Guthrie (1912-1967), one of the prerock figures who helped define what would eventually become the music’s purpose and intent. The strain of idealism that runs through rock and roll can be traced directly to him; he is, without question, as significant a symbolic figure as he is a musical one. Such songs as “Deportee,” “Do-Re-Mi,” and, most famously, “This Land Is Your Land” give voice to working people, immigrants, and the dispossessed—populations as much in the news now as they were back in the 1930s and 1940s, when Guthrie was helping to shape the very notion of what our country could be.

As both a person and a performer, Guthrie epitomized the freedom inherent to the American character. He sought to live untethered by conventional responsibilities, to travel the broad vistas of the country’s landscape, and to experience the great diversity of its people. He also embodied the conviction that such freedom should be available to everyone, to all the people in all the towns and villages he visited. Guthrie and his acoustic guitar became emblems of every person’s ability to sing out against injustice, using nothing more than his voice and a simple, portable instrument to give compelling expression to ardent beliefs. The slogan that famously adorned Guthrie’s guitar—“This Machine Kills Fascists”—proclaimed his faith that music could be at least as potent a weapon in the battle for liberty as a gun or any other means of destruction. With this deeply held worldview, Guthrie implied a larger inspirational movement: if one man could stand boldly against the enemies of freedom, what might a larger group achieve? In the great American tradition, Guthrie represents an individual voice articulating a collective message, one man speaking out for an uplifting national vision.

Hopping freight trains and hitting the road whenever the urge struck, Guthrie was not precious about his guitars, notwithstanding his belief in their power. He often picked up instruments and left them behind in the course of his sojourns—or gave them to needier musicians. But he was especially fond of guitars by Gibson (notably the Southern Jumbo) and Martin.

Woody Guthrie and his fascist-killing Gibson L-00, circa 1943

Woody Guthrie and his fascist-killing Gibson L-00, circa 1943

Bob Dylan (born 1941) is the primary inheritor of Guthrie’s stature, both musical and symbolic. When he came on the scene in the early 1960s, he was viewed as Guthrie’s second coming, and his acoustic guitar soon became as emblematic as Guthrie’s own. Dylan was quickly draped in Guthrie’s mantle as a socially conscious folksinger—and, like Guthrie, he wasn’t fussy about his instruments at first. He frequently lost and borrowed guitars but, again like Guthrie, eventually grew partial to Martins and Gibsons. Performing songs like “Masters of War” and “Blowin’ in the Wind” from a flatbed truck in Mississippi or at the 1963 March on Washington at which Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, Dylan and his acoustic guitar represented youthful idealism speaking out against the injustices of the time. Even Dylan’s harmonica, worn on a neck brace designed by Les Paul, took on symbolic weight. Played with the same lips that enunciated the singer’s righteous views, the harmonica became a sonic metaphor for his voice and his lyrics, delivering long, deftly articulated melodic lines that were like extensions of his verses. Dylan’s guitar and harmonica stated a clear message before he sang a word: if you had enough conviction, you didn’t need an accompanist—you could do the work of two musicians and carry your instruments wherever your message needed to be heard.

The image of Dylan with his acoustic guitar continues to resonate as a symbol of hope and bravado. To this day, the first wail of his harmonica in concert incites roars of approbation from his audience, those squealing tones proof that, no matter how many years have gone by and how many changes Dylan and the world around him have undergone, that young man of conviction is somehow very much present. When people describe Dylan as “the voice of a generation,” it is the image of him with his acoustic guitar they are thinking of, the angry young man on a high-minded mission.

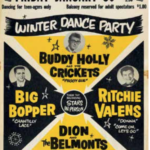

Posters (click for captions):

- Woodstock Music and Art Fair, August 15–17, 1969. The festival relocated from Wallkill to Bethel, N.Y., in response to local opposition.

- Monterey (Calif.) International Pop Festival, June 16–18, 1967

- The Beatles at Shea Stadium, New York, August 23, 1966

- Newport (R.I.) Folk Festival, July 22–25, 1965

- Winter Dance Party tour at Fort Dodge, Iowa, January 30, 1959. Four days later, three of the featured performers—Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper—died in a plane crash after a concert in Clear Lake, Iowa.

- Free concert at Altamont Speedway, Livermore, Calif., December 6, 1969, with the Rolling Stones headlining. Altamont, expected to be the Woodstock of the West Coast, instead descended into violence, including the stabbing death of a concertgoer.

After helping to enshrine the meaning of the acoustic guitar in his early career, Dylan dramatically dismantled his image at the Newport (Rhode Island) Folk Festival on July 25, 1965, the first of his many disruptive transformations. That night he took the stage not as a singular voice preaching social justice but as the front man of a roaring six-piece rock and roll band. The message he delivered to the folk faithful who gathered in Newport annually was not one they all wanted to hear. He was breaking free of that audience’s expectations and creating a sound that, rather than looking to the past, exploded with the insistent force of modernity.

Bob Dylan with his 1964 Fender Stratocaster in his first electric performance, at the Newport (R.I.) Folk Festival, July 25, 1965. Dylan’s controversial shift at the festival from acoustic to electric guitar is considered the birth of electric folk rock.

Bob Dylan with his 1964 Fender Stratocaster in his first electric performance, at the Newport (R.I.) Folk Festival, July 25, 1965. Dylan’s controversial shift at the festival from acoustic to electric guitar is considered the birth of electric folk rock.

The Fender Stratocaster guitar he strapped on for that show was as much a symbol of his boldness as the black leather jacket he was wearing. Many in the folk world had embraced the high-mindedness of the music they loved, deeming it morally superior to the commercial sounds of rock and roll, which they viewed as simplistic music for teenagers. Pete Seeger, a righteous emissary of the old guard, complained that the noise of electric instruments made it impossible to hear the lyrics. But in the wake of the excitement that had greeted the American debuts of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones the year before, Dylan realized that a smart young audience for rock and roll was taking shape, new listeners ready for new sounds. The deafening noise Seeger complained about delivered as powerful a message as any in Dylan’s lyrics.

The 1964 Fender Stratocaster Dylan played at Newport.

The 1964 Fender Stratocaster Dylan played at Newport.

At Newport, Dylan played just three songs with his electric band—when you’re inciting a revolution, you don’t need to play for hours—followed by a two-song solo encore, once again playing a

borrowed acoustic guitar and harmonica. When he closed his performance with an impassioned acoustic version of “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue,” his message could not have been clearer. The electric guitar represented the sound of his liberation and his future; the acoustic guitar, his past.

Indeed, by the mid-60s, the electric guitar had become the central instrument of rock and roll, overwhelming the honking, squalling saxophone that had vied for that position in the 1950s. The transition began slowly. The so-called king of rock and roll, Elvis Presley (1935–1977), played acoustic guitar, but it was more of a prop, an extension of his wardrobe, than an essential element of his sound—he had the incomparable Scotty Moore on electric guitar to take care of that. But just like the swiveling hips it rested on, Presley’s guitar read rebellion. Though it took a back seat to his vocals and his sexually provocative physical performance, the guitar reinforced the new generational figure Presley was helping to define: the rock and roll star. In time, though, the electric guitar seized the lead as the voice of rock and roll.

Elvis Presley played rhythm on this 1942 Martin D-18, one of his most important guitars, during his famed 1955 Sun Studio recordings, while Scotty Moore played electric guitar.

Elvis Presley played rhythm on this 1942 Martin D-18, one of his most important guitars, during his famed 1955 Sun Studio recordings, while Scotty Moore played electric guitar.

Presley onstage with his 1942 Martin D-18 at the Ellis Auditorium in Memphis, Tenn., February 6, 1955.

Presley onstage with his 1942 Martin D-18 at the Ellis Auditorium in Memphis, Tenn., February 6, 1955.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe (1915-1973) exerted a profound influence on the likes of Presley, Chuck Berry, and Johnny Cash and helped shape the uproarious sound of early rock and roll, though she has only recently begun to get the attention and recognition she deserves, including her 2018 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Combining the spiritual conviction of gospel music with the incipient energy of rock and roll, she sang up a holy storm and played her Gibson Les Paul Custom with both compelling rhythmic force and eloquently phrased lead lines. Her incendiary 1964 performance of the gospel standard “Didn’t It Rain” on The Blues and Gospel Train was a roaring milestone in her career—and in the history of British blues.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Brownie McGhee perform a blues number on Granada Television’s Blues and Gospel Train, recorded at the old Wilbraham Road railway station in Manchester, England, on May 7, 1964.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Brownie McGhee perform a blues number on Granada Television’s Blues and Gospel Train, recorded at the old Wilbraham Road railway station in Manchester, England, on May 7, 1964.

The show, recorded on May 7 in Manchester, England, for Granada TV, also featured Muddy Waters, the Reverend Gary Davis, and Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. It was set in an abandoned train station, where Tharpe was dropped o by a horse and carriage, a bit of stage business meant to evoke the American South. By all accounts, Tharpe’s performance was the show’s highlight. “When she strapped on her guitar, it was astounding,” recalled Johnnie Hamp, the show’s producer. The TV broadcast was viewed by millions, including such budding rock luminaries as Mick Jagger and Jimmy Page. It “influenced nearly everyone who saw it,” said CP Lee, a Manchester-based musician and cultural historian. “Young people saw it and thought, ‘Right, I need to form a blues band.’”

Elton John performing piano acrobatics during his U.S. debut at Doug Weston’s Troubadour in Los Angeles, a six-night run that began on August 25, 1970.

Elton John performing piano acrobatics during his U.S. debut at Doug Weston’s Troubadour in Los Angeles, a six-night run that began on August 25, 1970.

The piano, too, made its mark as a rock and roll instrument, with its own iconic moments. Unsurprisingly, the pianists who made an impact on rock and roll did so by exploding whatever associations the instrument may have had in the popular mind with polite parlor music, highbrow classical composers, and compulsory childhood lessons. Instead, they drew on the barrelhouse, honky-tonk, and boogie-woogie traditions of rockabilly, country, and rhythm and blues, and they created outsize characters that the piano’s large scale couldn’t dwarf onstage. However virtuosic their playing skills, they turned the piano into a percussion instrument, pummeling its keyboard as if trying to pound out any residual prissiness and classicism—delivering the message “Roll over, Beethoven, and tell Tchaikovsky the news” with pulverizing force. These excesses were not merely theatrical but also musical—another means of extending the sonic reach and daring that rock and roll represented.

The master in this field is Little Richard (born 1932), whose playing and singing distill the anarchy that drives rock and roll at its most untamed. Jerry Lee Lewis (born 1935) also rocked the piano as if its limitations needed to be physically annihilated. He would send his stool hurtling across the stage, as if to reject any insinuation that he would accept the passivity of remaining seated while he played. He would then hammer the keyboard with the heel of his shoe, the power of his hands and fingers—and elbows—inadequate to the punishing task he had set for himself. It is rumored that he once ignited his piano as he ended his set, appropriately, with “Great Balls of Fire.” Apparently furious that Chuck Berry had been chosen to close the show, Lewis wanted to make sure Berry knew what he was up against as piano battled guitar for rock primacy. Billy Joel (born 1949), who may have defined the category of the pianist/entertainer with his ballad “Piano Man,” never went to the extremes of Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis but has been known to send his piano stool flying, bounce his backside on the keyboard, and climb on top of his piano and leap off.

But the piano’s truly iconic moment was the American debut of Elton John (born 1947) at the Troubadour in Los Angeles in 1970. His six-night stand at the legendary club, beginning on August 25, quite simply made his career. His self-named second album (his first to be released in the United States), out barely a month, drew a critical mass of curious musicians, industry movers and shakers, and rabid fans whose unrestrained response to the shows propelled John into the stratosphere. John would eventually come to favor nine-foot Yamaha grand pianos, but at the Troubadour he played the club’s modest house piano. There was nothing modest about the performances, however, leading the Los Angeles Times accurately to declare that John was going to be “one of rock’s biggest and most important stars.” John later described his antic approach to performance as a counterforce against his large, static instrument: “You’re kind of [stuck] at a nine-foot plank and you’ve got to do something about it. So my thing was to leap on the piano, do handstands and wear clothes that would draw attention to me because that’s the focus of two and a half hours.”

More than most pianists, guitarists can readily command the stage, the greatest of them

conjuring some of rock’s most mesmerizing moments. History was in the making just about any time Jimi Hendrix (1942-1970) performed. For a master like him, the bigger the stage, the more significant the moment, the greater the heights to which he would rise. At the Monterey International Pop Festival in June 1967, the launch of the Summer of Love, Hendrix delivered one of the most legendary moments in the history of rock and roll. As his band blasted through its version of “Wild Thing,” he set his hand- painted Fender Stratocaster ablaze in a kind of ecstatic ritual, an effort to outdo the Who’s Pete Townshend, who had just smashed his Fender Stratocaster on the same stage.

Hendrix’s pyrotechnics were equally powerful when they were merely metaphorical. As the closing act at the Woodstock Festival in August 1969, Hendrix articulated one of the definitive instrumental statements of our time with his monumental version of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Hendrix was not given to overt political commentary, but his anguished, violent, transcendent rendition of the national anthem said more than words ever could. The Vietnam War was raging at its height that summer, and Hendrix channeled all the pain, suffering, and anger of that conflict through the roar of his white Fender Stratocaster. His performance of that song at the festival, a high point of counterculture idealism, gave poetic meaning to the concept of a Woodstock Nation: a new country shaped by the values of peace and justice standing in opposition to the brutal American war machine. That Hendrix was African American—and identified strongly with his Native American heritage as well—and had served in the military lent his performance even greater depth, weaving all the frustrations and hopes of the civil rights movement into his sonic vision of a nation riven apart and desperately hoping to come together once again.

__________________________________

Excerpted from “Iconic Moments” by Antony DeCurtis in Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll. Copyright © 2019 by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Reprinted by permission.

Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll accompanies an exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, on view through October 1, 2019. The book is available for purchase at The Met Store and Yale University Press.