Timing is everything.

It was my great good fortune to come out as a gay man in 1970, the year after the Stonewall Riots began the gay liberation movement. Like every gay man or lesbian my age, and everyone else on the widening continuum of the sexual other, I was given an extraordinary gift: I am alive at the best time to be gay since Aristotle.

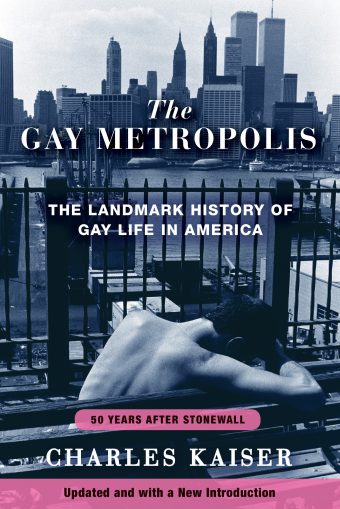

This new edition of The Gay Metropolis is a celebration of this astounding era. It’s also an expanded history, now spanning eight decades of our culture, instead of the original six. It remains an homage to a tiny number of extraordinary people—the pioneers who had the power, the wisdom and the vision to launch a movement which, at its birth, was wholly implausible, and its allies non-existent. In many of the great metropolises of the world, after just five decades, it has nearly dismantled twenty centuries of prejudice.

World War II was the roaring engine that made all the modern liberation movements possible. It did this in several ways. First it gave women, blacks, gays, and lesbians vital new paths toward self-esteem, by becoming everything from factory riveters to fighter pilots. Black soldiers proved they were the equals of everyone; women left the hearth to thrive in the jobs their husbands had vacated; and gay men and lesbians who had thought they were uniquely afflicted discovered a vast new gay world beyond Kansas. After the war, gay veterans often resettled together, revitalizing big-city neighborhoods that would become the nuclei of our movement twenty-five years later.

There was also the crucial effect of the Nazis’ crimes against the Jews. They were so gigantic, then reenacted so graphically at Nuremberg, that they produced an unprecedented revolt not only against anti-Semitism, but, gradually, against almost every other form of bigotry.

President Harry Truman’s decision to integrate the armed forces was the first big postwar victory of the black Civil Rights movement. This was the opening volley in a much broader battle for equality. The bravery of African-Americans was crucial: their example inspired all the rest of us.

Twenty years after the war ended, the Civil Rights movement finally became a real American success story—an ennobling moment for the nation. The imperfect triumphs of this great crusade melded with all the other explosions of the 60s, upending centuries of certainties. This made both the gay movement and the women’s movement possible.

At the beginning of the 1970s, the novelist Merle Miller caused a sensation when he came out on the cover of the New York Times Magazine. No one had done that before.For gay people in their twenties in New York and San Francisco, the 1970s was our decade of literal wild abandon, with sex in the bedrooms, the back rooms, the Continental Baths, the basement of the Anvil and the bushes of the Ramble. Our in-your-face promiscuity was proof of our liberation. When the lights went out in 1977, in the second great New York Blackout, the darkness shrouded looting on the Upper West Side and sparked huge fires in Brooklyn and mayhem all over the South Bronx. Not in Greenwich Village. In minutes gay men emptied the bars, turning Christopher Street into a naked, carnal conga line stretching from Seventh Avenue to the Hudson: Fellini Satyricon, undulating in the darkness.

Just a decade after Stonewall, our joy was halted, buried under unspeakable loss. The AIDS epidemic took the lives of half the gay men of my generation. It was numbing, and yet, simultaneously, transforming. Faced with casualty rates reminiscent of the Battle of Argonne, we fought back with a surge of activism. We were engulfed, but not extinguished. We revolutionized our status. Lesbian caregivers bonded with gay victims. And then, somehow, Larry Kramer figured out how to harvest hope from all the trauma. Looking over the edge of the abyss, he used it to galvanize successive generations of young activists, first with the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and then, even more dramatically, with ACT UP.

His visceral fury prevailed: You shall not ignore us.

As David France explained in his great book, How to Survive a Plague, these zealots for life transformed the way new drugs were introduced. They worked with scientists so effectively that AIDS became a manageable disease instead of a death sentence, just fifteen years after the New York Times reported the first cases. The response of the federal government under Reagan and the first George Bush was shamefully slow—murderously so—because most of the victims were gay, including the most self-hating gay Republican of them all, Roy Cohn. But in the second decade of the epidemic, gay activists stimulated head-spinning scientific progress.

Thanks to these indefatigable fighters, millions of us managed to reach an era when being HIV-positive is no more of a physical burden than diabetes, at least for those fortunate enough to receive the best medications. By 2018, almost everyone with prompt access to the newest generation of protease inhibitors was not only “undetectable,” but also “untransmittable” to their partners—meaning they could no longer transmit the virus to anyone, even during condomless sex. Another new pill marketed as PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) proved equally effective at preventing people from being infected in the first place.

*

No matter your sexual persuasion, it may be hard to imagine just how invisible and despised homosexuals had been for centuries—even millennia. Even straight members of my generation are often shocked when I remind them of a detail from the dark years, before the words “gay” and “liberation” had ever appeared together. “How could that have happened?” is a question I’ve heard often.

In 1965, Frank Kameny, Jack Nichols, Barbara Gittings, Paul Kuntzler and half a dozen other brave hearts put on suits and ties and Peck & Peck dresses to form the first gay picket line outside the White House. These were the first gay activists of the sixties, unknown to anyone except each other. When the public saw their signs demanding justice for fifteen million American homosexuals, they were flabbergasted. “People passed by in disbelief,” Kuntzler remembered fifty years later. “It was written on their faces. It had never happened before.”

At the beginning of the 1970s, the novelist Merle Miller caused a sensation when he came out on the cover of the New York Times Magazine. No one had done that before. Doctors told Miller that if they followed his example, “they would lose their patients; lawyers wrote that they would lose their practices; writers would lose their readers; a producer would not be able to raise money for his next musical.”

Millions of gay men and women were married to members of the opposite sex because they believed that was a necessary step. Their spouses were another kind of casualty.These fears were not outlandish. I felt them too. It was still the official position of the American Psychiatric Association that every homosexual required treatment for a curable disease. A decade later, at the onset of the AIDS epidemic, there still wasn’t a single openly gay reporter or editor at the New York Times. Even in gay-friendly San Francisco, a brilliant young man named Randy Shilts was the only “out” reporter at a daily newspaper.

There were, of course, millions of successful homosexuals everywhere: inside the army, the Navy, and the Air Force; in the House, Senate, and White House; in statehouses, courthouses, and city halls; in churches and synagogues; on movie sets and Broadway stages. But millions of these men and women were also married to members of the opposite sex because they believed that was a necessary step. Their spouses were another kind of casualty. And almost every gay person (married or not) remained deep inside a stifling closet.

For two decades the most successful politician in New York City was Ed Koch, a Manhattan congressman who became a very effective three-term mayor. With ego and intellect and the finest political antenna since La Guardia, he massaged the city back to life, after its brush with bankruptcy just before his inauguration in 1978. “A Mayor as Brash, Shrewd and Colorful as the City He Led,” the Times put it.

Koch was hated by gay activists who believed his hidden sexuality prevented him from responding forcefully to the AIDS epidemic. As the great gay political pioneer Ethan Geto has told me, Koch could have given his gay brothers vital succor when they needed it most, if he had found the courage to leave the closet at the height of the epidemic. But like every gay politician of his generation, he was certain that all of his success had only been possible because he had kept this secret.

Unlike most other closeted public officials his age, he actually had a long pro-gay record, which included his opposition to anti-sodomy laws in the ’60s; his introduction of a nondiscrimination bill in Congress in the ’70s; and an executive order banning discrimination against gay people by the city government, which was practically his first official act as mayor. Years after he left office, he told an interviewer, “Some of the voters think I’m gay, some of them don’t—and most of them don’t care.”

In private, he was a different person: a natural and seemingly unconflicted gay man. The first time we had dinner alone, it began this way. “Do your parents know that you’re gay?” he asked.

“They do,” I answered.

“Too late for me,” he replied. “Whenever I see two men holding hands on the street,” he also revealed, “I think to myself I’ve done something right.” Activists, of course, would be horrified that he took credit for that.

Some of my friends are uncomfortable with my decision to write about his secret, such as it is, in this new edition of The Gay Metropolis. He didn’t want me to, but I never promised him a posthumous silence. Like many early activists, I have always believed in speaking the whole truth about the dead; that has been an essential building block for our movement. It would have been impossible to suggest the breadth of our history if we had agreed to keep so much of it invisible. By retaining these confidences of our forebears, we could only make their shame our own.

This is how the writer John Birdsall explained his outing of the legendary chef James Beard in 2013. “What I’m doing is to sort of find the traces of those erased lines in his story and to fill them in again,” Birdsall said. “Beard didn’t feel like he was able to live in an authentic way, and so I feel like I’m kind of perhaps allowing him to do that, posthumously.”

I feel exactly the same way about my friend Ed.

*

My life and the lives of millions of others have been fueled by these changes for good, especially the possibility to be completely open about who you are. They gave us the glittering prize that was almost always out of reach for our gay ancestors: personal authenticity.

New York city council speaker Corey Johnson personified all of the progress new attitudes have made possible. His career as a proud, openly gay man started a couple of days after his eighteenth birthday, in April 2000, when he came out on the front page of the New York Times as the gay co-captain of the Masconomet High School football team in Topsfield, Massachusetts. The great Times sportswriter Robert Lipsyte called Johnson “a rare find” for gay activists trying to shatter stereotypes: “a bright, warm quick study. . . .For athletes, whose socialization often includes the use of homophobia by manipulative coaches, he is a liberating symbol.”

Thanks to all the efforts of earlier activists, Johnson also had something that wasn’t there thirty years earlier: a gay infrastructure online.Lipsyte’s article is one of the most moving coming-out pieces ever written. “Someday I want to get beyond being that gay football captain,” Johnson told the Times reporter. “But for now I need to get out there and show these machismo athletes who run high schools that you don’t have to do drama or be a drum major to be gay. It could be someone who looks just like them.”

When, as a teenager, he first began to understand his true nature, Johnson felt the usual misgivings about being different. He had heard his uncle’s homophobic rants during the Super Bowl. But he was also part of the first generation with a whole new electronic universe to diminish loneliness. He had the Internet. Almost immediately he found his way to Planetout.com, where he could chat online with other gay kids—even other gay football players.

Thanks to all the efforts of earlier activists, he also had something that wasn’t there thirty years earlier: a gay infrastructure. At school he joined the Gay Straight Alliance, but that didn’t strike his classmates as suspicious, because he was already known as a champion of kids who were being bullied. In the spring of 1999 the group’s faculty adviser took the group to a regional conference of the Gay Lesbian and Straight Education Network. At the end of the session, Johnson raised his hand and said he was a football player, and he wanted to come out.

GLSEN’s Northeast coordinator, Jeff Perrotti, immediately recognized that this was a revolutionary moment: “A football captain is an icon. And one coming out would raise the expectations of what was possible. It would give hope.” Johnson’s story on the front page of the Times indeed gave gay kids and gay athletes hope, all across the country. It also soothed the fears of many of their parents.

In 2004 he found out he was HIV-positive. He felt shame, fear and anxiety, and he “didn’t think it could get any worse.” Almost immediately, it did: a couple of weeks later he lost his job and his health insurance. But this time, his life was saved because he was a New Yorker. The city that had once failed to provide enough hospital beds for all the young men dying of AIDS had been transformed over two decades. Because of Larry Kramer and his armies of activists—and a handful of straight allies, like Mathilde Krim at AMFAR—New York had become one of the best places on earth to get treatment for this virus.

Johnson’s doctor sent him to the Apicha Community Health Center in Manhattan’s Chinatown. “I remember walking from Chelsea to Chinatown nervous and scared,” he said, “and they sat me down with this incredible woman named Shefali, who became my caseworker. She was vibrant and loving and reassuring and with zero judgment, just compassion. She found me a doctor and she got me enrolled in ADAP [the AIDS Drugs Assistance Program].”

“For days and months and even years,” he continued to live with that “shame and fear and anxiety.” To blunt his depression, he self-medicated with drugs and drink. After five years he got sober. In 2012 he announced his candidacy for the City Council—and also announced he was HIV positive. He was running in the district once represented by Tom Duane, one of the first politicians anywhere to announce that he was HIV-positive in 1991. In 2013, Johnson was elected with 86 percent of the vote. Four years later, he was reelected, and, in January 2018, he was sworn in as speaker of the City Council, making him the second most powerful politician in New York City government.

This was an extraordinary arc: the most rapid political ascent in New York in my lifetime. At the beginning of 2019, he met the expectations of his supporters by announcing that he was ready to run for Mayor. A few months after becoming speaker he received the Larry Kramer Activism Award from the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, in a ceremony in the grand ballroom of the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. “Today I do not live with shame,” said Johnson. “For years,” he continued,

it ate me alive. Today I try to use the position I have . . . to hopefully lessen the stigma surrounding HIV/AIDS. I do it on the shoulders of all the brave men and women who came before me. The ones who put their lives and bodies on the line which, in the end, when I found out I was positive, is why I had access to lifesaving medication. It’s important for people who are in the place I was in 14 years ago to hear my story and know that there is life—a full, happy, wonderful life—after diagnosis. I am grateful every day and take nothing for granted.

He did not forget to remind his fancy audience of others who were less fortunate. “People are dying of HIV/AIDS in 2018,” he said. “Today,

HIV has become a disease of poverty. The people who are getting infected in 2018—a lot of the time, they don’t look like me. They don’t look like a lot of the people in this room. For the most part, they’re black and they’re brown, and they’re very poor. In a lot of cases, they’re black women. They don’t look like me, but I know how they feel. The same way I felt 14 years ago when I was walking to that clinic in Chinatown. They’re scared and they’re anxious, and they think they’re going to die of this disease. The truth is, without the right help, they probably will. So yes, we have come far. But we have far to go.

He also remembered to thank all the people who had gotten him to this remarkable place, where he lived as a proudly public gay man, the opposite of Ed Koch, the gay mayor who had dominated the city’s political landscape a generation earlier. “To the warriors who risked it all—those of you here in this room, not here, dead or alive—your work was there waiting for me when I needed it,” he acknowledged. “I know what happened; I know why I am here. I will never forget and I will always be grateful. I work in the East Wing of City Hall in an office with a photo of Larry Kramer and a Silence Equals Death poster as an openly-gay, HIV-positive man—and no one bats an eye. I am accepted.”

I believe that the waves of history are still crashing toward righteousness. Part of my optimism is grounded in demographics. Since World War II, every new generation has been more accepting of difference than the one before it.Of course, this good news is only part of the story. In many places across America, and many more around the world, the hatred against gay people remains as powerful as ever. The election of Donald Trump presented American democracy with its greatest challenge since we prevailed in World War II. We have a president whose ghastly example has given every bigot in America permission to behave as badly as they ever have. (In Brazil, president Jair Bolsonaro is an even more virulent version of our own ghastly leader.) Johanna Eager of the Human Rights Campaign told the Times that since Trump’s election, she had heard of “some of the most horrible hateful situations in schools that I have not experienced in the past almost 30 years.”

Faced with an administration so broadly contemptuous of decency, it’s difficult to specify which of its actions have damaged the country the most. But two of its most hateful policies were aimed squarely at transgender people.

First, the president announced that he would kick every transgender soldier, sailor, and airman out of the armed forces for no reason whatsoever, except for the hateful prejudices of his supporters. That was quickly followed by another heinous proposal. A memo leaked from inside the Department of Health and Human Services advocated a new policy that would write transgender people out of existence, at least in the eyes of Washington bureaucrats. The report said “government agencies needed to adopt an explicit and uniform definition of gender determined on a biological basis that is clear, grounded in science, objective and administrable.” In a huge step backward, “gender would be defined as male or female, unchangeable, and determined by the genitals that a person is born with. Any dispute about one’s sex would have to be clarified using genetic testing.”

With ideas like this bubbling up from the Trump administration, many naturally began to worry that the progress of the last fifty years was now in jeopardy. As Barack Obama is fond of pointing out, every two steps toward justice are often followed by one step backward.

But I believe that the waves of history are still crashing toward righteousness. Part of my optimism is grounded in demographics. Since World War II, every new generation has been more accepting of difference than the one before it. Even Obama pointed out that one reason he changed his position on marriage equality was his acquaintance with the gay parents of some of his children’s school friends—and the bafflement of his own daughters at the idea that gay parents would be treated any differently from straight ones.

At Dalton, one of Manhattan’s most prestigious private high schools, Wolf Hertzberg told me he witnessed this scene in his senior year in 2016:

At a school assembly, ten LGBT faculty members formed a wide semicircle around the microphone—there was an element of ceremony to it—and waited, standing, while one by one each teacher came to the mic to read their piece. Each of them recounted their experience of being an LGBT person both in their personal lives and in the school community. Every single teacher received thunderous applause and wild cheers from the students, and was warmly applauded by their colleagues onstage. The whole thing was incredibly moving. I actually think back on that hour as the highlight of high school. It was one of the great privileges of my life to have witnessed it.

Even as the Trump presidency threatened everyone’s faith in progress, there was no regression toward prejudice on the artistic side of the country. After the success of Brokeback Mountain early in the new century, there was a flood of new gay-themed movies and television shows—everything from Milk, a great filmed biography of the San Francisco supervisor who was assassinated after becoming one of that city’s first openly gay elected officials, to Moonlight, the breakout hit about three stages in the life of a young African-American in Miami, which was nominated for eight Oscars and won four of them, including best picture.

Tremendous battles for justice still lie ahead. But at the end of the second year of the Trump presidency, there was dramatic new evidence that decent Americans are still in the majority.Twenty-first-century culture continues to push America in a hopeful direction. The last generation of haters is dying off, and a new generation is poised to transform America. The younger you are, the less likely you will share the sexual prejudices of your elders. In Weston, Connecticut, Natalie Ponte was grooming her four-year-old son Milo to be a future freedom fighter by reading him an LGBTQ-themed children’s book called A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo. The Times reported that Ponte had written on Facebook that the experience was transformative. “We are pretty open and progressive and this kid still had reservations at the beginning about two boy bunnies getting married,” Ms. Ponte declared. But “[a]fter reading this book twice he was ready to run for office on a gay rights platform.”

Tremendous battles for justice still lie ahead. But at the end of the second year of the Trump presidency, there was dramatic new evidence that decent Americans are still in the majority. It took a couple of weeks after the election of 2018 for all the good news to trickle in. By the middle of November, it was clear that the voters had sent a tremendous new wave of black, brown, gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender candidates into office.

In January, a lesbian and a bisexual were sworn in as members of the United States Senate and eight LGBTQ candidates took their seats in the House, record numbers for both chambers. Across the country 150 others were elected, including a new gay governor of Colorado. In Iowa, the charismatic Zach Wahls became the first candidate with two moms elected to the state senate. Seven years earlier, he had captured the imagination of the Internet with a remarkable speech before the Iowa legislature. “In my 19 years, not once have I ever been confronted by an individual who realized independently that I was raised by a gay couple,” he said. “And you know why? Because the sexual orientation of my parents has had zero affect on the content of my character.”

The new year also welcomed the first plausible, openly gay candidate for president, Pete Buttigieg, the thirty-seven-year old mayor of South Bend, Indiana, who had come out during his second mayoral campaign—and then got reelected with more than 80 percent of the vote. The Rhodes Scholar and Afghan War veteran was an instant hit in his first national TV appearances on Morning Joe and The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, where Colbert noted that the fact that Buttigieg was gay was “only the third thing” you learned about him.

More than ever, I believe in the words of Bobby Kennedy, which he delivered in South Africa on its Day of Affirmation in 1966: “The answer,” he declared, “is to rely on youth—not a time of life but a state of mind, a temper of the will, a quality of imagination, a predominance of courage over timidity. A young monk began the Protestant Reformation, a young general extended an empire from Macedonia to the borders of the earth, and a young woman reclaimed the territory of France . . . [It was] a thirty-two-year-old Thomas Jefferson who proclaimed that ‘all men are created equal.’”

I am confident that a formidable new generation of Americans will find the courage, the power and the wisdom to proclaim the equality of everyone.

__________________________________

Charles Kaiser’s The Gay Metropolis is out now from Grove .