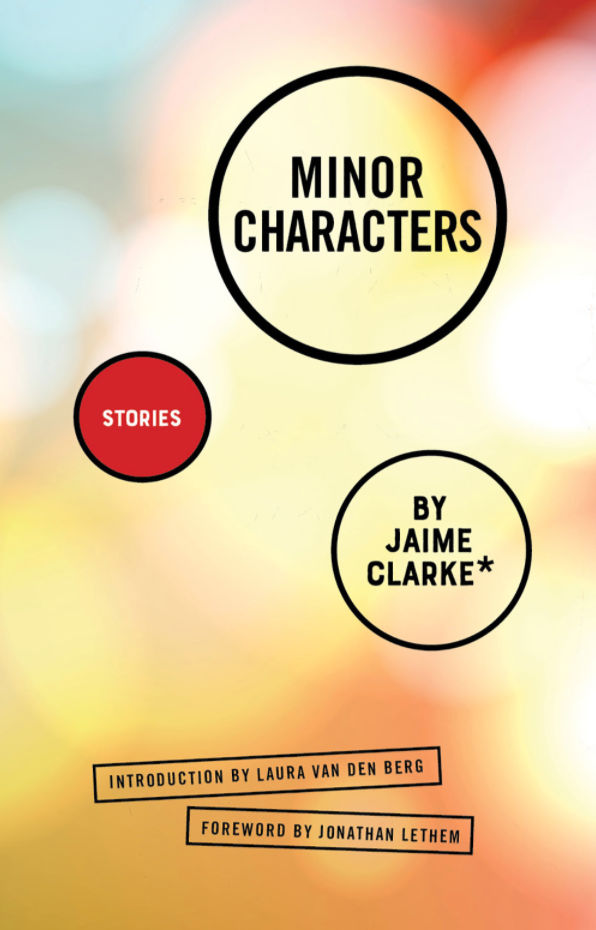

All novels are necessarily concerned with their protagonists, but what of the minor characters that fill out a novel’s landscape? We can never know them as well as we should or like. The same is true for the trilogy of novels by Jaime Clarke: Vernon Downs, World Gone Water, and Garden Lakes. Minor Characters brings together Clarke’s previously published short stories featuring the supporting characters in his trilogy, as well as stories by some of today’s most talented contemporary writers, who have chosen characters from the trilogy and contributed a story.

Featuring original stories by Mona Awad, Christopher Boucher, Kenneth Calhoun, Nina de Gramont, Ben Greenman, Annie Hartnett, Owen King, Neil LaBute, J. Robert Lennon, Lauren Mechling, Shelly Oria, Stacey Richter, Joseph Salvatore, Andrea Seigel, and Daniel Torday. With an introduction by Laura van den berg, and a foreword by Jonathan Lethem: “Clarke has done more, even, than Vonnegut in setting his characters free: he’s flipped foreground and background, and at the same time invited others in to browse, and revise, and interfere with, and extend, his fictional who’s who.”

__________________________________

A Way to Beat Mortality

By Shelly Oria

If you want to meet girls who are real hungry for it, the psych ward is where you want to go. I say this to my buddy Pete, and Pete says, “That the new bar down on Fifth?” I need to stop wasting my calls on him is what I need to do. “Focus, Petey,” I tell him. “Where am I calling you from?” “Oh,” he says. “Cool.”

The conversation is going nowhere, so I can’t even tell him about Cheeky, which was the whole point of the call. Because what was I going to do, bring it up in group? “Fatty over here and me got something we want to share”? Or whisper to my roommates after lights-out, “Cheeky’s got a wild side like you wouldn’t believe, like no other girl I ever seen”? Say, “Touching her feel like you rolling your whole hot body in snow”? Course not. We all know each other here. That kind of talk would be disrespectful. And if I learned one thing from my relationship with Talie, from her death, from coming so close to death myself that I held it in my mouth and it tasted like rust, like failure, like the end of air—if I learned anything from all that, it’s that respect matters. Had Talie and I treated each other with respect, had we respected ourselves enough to respect each other, she’d still be alive. Some things are simple.

Pete can’t focus most of the time and it’s not his fault; he’s got a thing where the left part of his brain checks out if he smokes even half a joint. And what’s he going to do, quit smoking? He needs his pot the way I need the hospital. Petey and me, we got in trouble selling a building that couldn’t be bought. We had no idea we were doing anything wrong; we didn’t mean the illegalities that happened. Turns out in real estate, good intentions don’t matter. In a year or two or three, when the investigators decide they’ve concluded their investigating, we may be able to breathe right again, or we may be facing a jury of our peers. Every time we talk, I say to Petey, “You get yourself some help like I did and you won’t have to smoke till you numb.” If his head’s straight when I say it, he gives me a hard time. “Daley, my man, we both know what help you really there for.” He thinks the hospital is my backup plan to avoid jail. Strategizing is what he calls it. “You just strategizing, D.” He’s not wrong, but he’s not right, either.

Cracking a joke about a hidden gun would likely be a bad idea.I show up to group in the afternoon fresh from my call with Pete, and Cheeky’s chair is empty. Technically, it’s just another chair like any other chair; seats aren’t assigned in group, and this is something we’re told once a week at least, asked to repeat back—it seems important, maybe because it’s bad to indulge the OCDs, maybe for some other reason. In reality we all know which chair is whose, and this is one way in which everyone’s respectful. So I don’t need to look around; I know right away Cheeky’s not in the room. I sit down, and soon as we get started, I say I want to share. What I share is a story Petey just told me on the phone about a girl we know: she got a dog-sitting gig and the dog died. I make this my story that happened in my formative years. I tear up a little describing the dog’s eyes going out, touching the flap of his ear for the last time. Stepping out of the vet’s cold office, calling my aunt to tell her Donut’s gone. And sure, I’m lying, and some people in the room even know it, I bet. But there’s a world in which every bit of my story is true, and most of the time that world is where I live. When I cry, it’s because I loved that dog. It’s because I fucked up.

I often call Pete right before group. “Buddy, give me material for a preempt,” I tell him, and he just talks then, talks about anything at all. There’s usually something in his words that I can use. I try to preempt with a share if I can, so no one will ask about Talie. These people love to ask about her, about how she died, even though I know they know everything. Painted into a corner, I’ll say, “Look it up.” This happens in group and also in my one-on-ones. They say things like, “It might be helpful to talk it through.” “Look it up” is maybe my way of saying “Fuck off” without cursing, which we’re not supposed to do, or maybe it’s my way of reminding everyone that I’m a little bit famous. “What’s the difference?” Cheeky asked when I said all this to her last week. “You’re just saying the same thing twice. Isn’t the whole point of fame to keep people at a distance, have everyone assume you want them to fuck off?”

Cheeky loses her sympathies when I complain about this place. She says it’s my delusions that make her impatient—“delusions” is a big word around here—that no matter what anyone asks me, I hear it as a question about my past. But I think she just gets jealous hearing me talk about Talie. I don’t say that, though, because I’m not an idiot. What I say instead is, “I wish you acknowledged my reality.” And to that Cheeky always shrugs, which I suppose is fair: she made the same point our very first conversation, months ago, and back then I responded with gratitude. She cornered me after my first or second group and said, “New guy, if you listen better, you’ll see most of the time no one’s attacking you.” I looked at her for long seconds, and she looked right back at me. The truth is I felt a shift, the beginning of a stretch, which made no sense—this girl did not look like someone my body would respond to, let’s say—and I was thinking I might be having a reaction to one of the medications. I said, “Thank you,” because it seemed like a good way to end the exchange.

The reason people around here love talking about other people’s delusions is that it’s sort of foolproof; if you accuse someone of being delusional about something, they can’t argue, because arguing would make them look delusional. That way you’re both keeping the heat off of yourself and supposedly making a valid point, being helpful to a fellow patient. My tactic with this is to accept the accusation; I’ll say something like, “You’re probably right. I struggle with delusions quite a bit.” Then I’ll just go on talking. It usually works.

So is Cheeky right, am I just imagining that everyone’s fixated on my past? Maybe. But I can tell you this: nine times out of ten, if I don’t preempt, I’ll get asked about the mess I made after Talie’s death, what people like to call a “shooting.” And the problem with this type of conversation is you let it start, it’s going to continue. That’s just how it goes with anything that’s ever been in the news: people want to touch it. As if talking about a shooting makes them survivors, as if proximity to violence could make them famous, as if fame is a way to beat mortality. Fame, at best, is temporary distraction from sadness.

People who don’t pay close attention conflate Talie’s death and the shooting, and I’m not good at keeping cool when that happens. Talie didn’t die in a shooting; Talie died in a Dumpster. This isn’t a dignified truth, but it’s the truth nonetheless. Talie died because she had the kind of friends that get you killed. And the kind of boyfriend, me, who lets death find you. A boyfriend who doesn’t say, “Stop hanging with Holly.” Who doesn’t say, “I swear to God, you fuck around on me one more time . . .” Who sleeps tight, doesn’t wake up with a knowing in his chest that something on the south side of town is wrong, because definitely if he did wake up with that type of tightness, he’d listen to it, act on it, wouldn’t fall back asleep. He’d go out into the night, into the almost morning, find his girl, and save her life.

“So we’re all obsessed with your past and also don’t care enough to remember the details,” Cheeky has said to me several times. She can sound clever, and a big part of her cleverness is she knows how to twist words around. “No,” I say every time. “Some people are nosy, and others don’t use their ears when I talk.” The thing about this place is you end up having the same conversations many times. We repeat our words because there are more hours to every day here than there should be. “No one around here thinks your ex died in a shooting,” Cheeky says, and usually what I say back is, “Please don’t say ‘shooting.’”

The main thing to know about the shooting is that it wasn’t a real shooting: no one got hurt. Look it up and you’ll see “no casualties,” but what does that tell you? It suggests maybe no one died but some were injured. It distorts the truth, because lies sell papers. And the thing about a lot of the people here, they’re the kind of people who read the paper. Also they are not critical thinkers. You explain to them about the types of distortions the papers are filled with, they say, “Call it what you want, but why’d you show up at that party with a gun?” They ask, but they don’t believe there’s an answer.

That party was a day or a month or a week after Talie’s funeral. I don’t know the specifics. A man hugging the floor, wasted with sorrow, high but lower than he’d ever been: what’s the difference to him between hours and decades, a week and a day, a lifetime? “I was grieving, is all,” I said once about that party, the gun, “grieving and angry.” My therapist nodded and closed his eyes. “And you didn’t have tools,” he said. “That gun was your tool.” Tools are what we’re learning: how to have them, how to use them. No store sells these types of tools, but anyone can buy them, we’re told, by showing up and working hard.

I want to have tools, I do. But I’m in no rush.

“This what you missed group for?” I ask Cheeky, meaning the mashed potatoes she’s moving from side to side on her plate. You dating a fat girl, you know where to look when she’s missing; nine times out of ten, checking the cafeteria will not be a waste of your time. Cheeky looks up. “What’d I miss?” “Nothing,” I say, “I told a story.” “Yeah,” she says, and pushes her plate away like I just killed her appetite. She shakes her head, a tiny movement, light as a thought. “Didn’t need to watch the Dale show today,” she says. She gets up to leave like clearing the plasticware is no thing we do. “Baby,” I say, “baby.” She likes it when I call her that, but she looks at me now like I offered her a taste of poison. “Don’t, Dale,” she says. Then her back is moving away from me.

This feeling is nothing new: I had it with Talie, had it before Talie, had it every time I put my thing in someone for more than two, three nights. You hold a woman tight enough, sooner or later she’ll be asking you questions. What I do now is I grab some stationery—Think Pads, they call them around here, and they’re everywhere—and start compiling a list. Ten, fifteen minutes later I am standing at Cheeky’s doorway holding some guesses. Cheeky is in bed reading a book. I have no doubt that she sees me, but she won’t look up. Instead she pretends to go on reading, or, knowing her, she may actually be reading. That’s what I love about her: she gives fewer fucks than maybe anyone I’ve ever known. I glance at my yellow pages. “This morning,” I say, “I brushed my teeth instead of waiting for you to go first. It was inconsiderate.” Cheeky’s eyes are still on her book. I scan her face, but she’s giving me nothing. Probably this first guess isn’t right and I should move on to the next, but how can I know for sure? She’s so . . . subtle. I think of Talie, the shit she’d have given me on the spot for this kind of move. I mean, you wake up with a woman for the first time and the bed is tight and the bathroom narrow, you don’t fucking claim space. You offer up the sink, you offer up the toilet. What was I thinking? Cheeky squints. Her forehead is lines and lines. “What?” she says. So I move on to number two. “Let me preface by saying I very much hope it’s not true,” I say. She says, “Okay . . . ?” “Are you maybe just wishing we stayed friends and never slept together?” I ask. Cheeky is still squinting. “Last night was fun,” she says, and then adds, “The physical part.” “Okay,” I say, “good. Good.” I look at my yellow pad. “Are you reading from a list?” Cheeky asks. “No,” I say. Now we are both looking at the yellow pad. “It’s not like that,” I say. “Okay,” she says. “I just,” I say, “I wrote down some possibilities for why you might be mad.” Something softens in her face when I say this, something opens up just a tiny bit. She sits up, puts her book on the pillow, taps the mattress with light fingers. I walk over, sit by her side. Our bodies are close now, and it takes all my willpower not to kiss her, but I know that would be the wrong move. We look at each other, and then she looks down at the floor. “Tell me,” I whisper. She looks back up, right into me, through me. “Do you really not know?” she asks. We both know the answer to this question. She shakes her head, but it’s such a small motion, the motion of a woman who wishes she were more surprised than she is. “For months you pursued me,” she says. I want to say, “We pursued each other,” but I know that’s the wrong thing to say, and once I let it stay in my mouth for a second, two, three, I can also tell that it’s untrue. She’s right. I have been pursuing her, and for a good while what she did in response was try to convince me to unpursue her. “I just wanted to be friends,” she says, and I nod. I hold her hand the way a dear friend would. “If you’re not . . . ,” she says. “If you don’t like . . . ,” Her words circle each other and me, forming a knot. I squeeze her hand, but so gentle it’s basically like I did nothing. “If I don’t like what?” I ask. “If I’m not your type,” Cheeky says, and her voice sounds different, sharper, “then . . . why? Why go after me?” We look at each other and I try to think fast, but generally speaking, thinking fast in these types of situations isn’t a strength of mine. I probably look like some animal in the wild, realizing that sound in the distance was the click of a rifle. I never said that she wasn’t my type, only mentioned that in the past she wouldn’t have been. It was a positive statement. Cheeky gives up on my eyes now, looks out the window. The windows here are so small. She lingers and lingers and at some point makes a face that’s almost a smile, so I wonder, I have to, what she’s seeing. Finally she says, “Let me tell you something as a friend.” “Yes,” I say, “of course.” There is no other thing I can say in this moment. Some things are simple: I care more than she does, so she has more power than I do. As long as she’s willing to talk, I will be here listening. “Fuck someone or don’t,” Cheeky says, “but if you do, then make no apologies.” I narrow my eyes at her. “I don’t understand,” I say, though for the last few seconds a part of me has been replaying our whole conversation from last night, and I’m hearing it for the first time. “You don’t need to understand,” Cheeky says, “just don’t ever tell a woman that you feel proud of yourself for fucking her.”

I’m moving fast after that, changing clothes, passing through hallways and doorways, signing a piece of paper at the front desk, something titled Voluntary Patient Temporary Leave, and Reviva says, “You okay, Dale? Maybe discuss with your doctor first?” and I say, “I’m cool, Reviva, I’m cool,” and she smiles at me like she believes in me, or maybe I’m so desperate for someone to believe in me that I’m willing Front Desk Reviva’s smile with my imagination. She says, “You haven’t filled out this part,” her finger pointing at a question on the form, and I say, “I won’t be gone very long,” and she says, “You need to be more specific,” and I chuckle like this is a joke we always tell, turn around to leave because this question feels suffocating, but Reviva’s face is saying, Answer my question or I’m not buzzing you out, so I say, “Four, maybe five hours,” and then I turn my back to her and then the main door, a heaviness I didn’t expect against my muscles, and for a quick moment it seems my upper body isn’t up to the task and I think, Maybe this is a mistake? Then I’m out.

The outside world is quiet, and I know it has quieted down just for me. I’m not being sentimental. It’s just what happens, the soundtrack of silence piercing through the air. I also know it won’t last; these gestures between Universe and Man, they are always brief. I’m not wrong, of course: a moment later I look around and everything is too much. The world has never been this beautiful, has never been this ugly, has never been this boundless. It is spilling, spilling all over. I see every detail all at once, and the thing is that the resolution is off. My eyes want to shut but I force them to stay open, then force them to imagine cubes, rectangles, sharp lines dividing the landscape. I can breathe again now, and what I do next is that I say hi. I say it out loud. I say it to the skies, to a tree, to the concrete under my feet, and the way that I say it is a flirt. I say hi like there’s a girl in front of my face that no one else can see. Hey, you.

Thirty minutes later Petey opens the door, saying, “What the . . . ?” I hug him and try to explain about the world. I say I felt attacked by the air but I fought back and maybe I won. I say something about pixels. “Don’t they ever let you go outside?” Petey asks. His question makes my body go small. It reduces my spiritual moment to exactly what you’d expect from any type of inmate. “There’s a backyard-type place,” I say, “but it doesn’t feel like it’s even outdoors at all.” Pete nods. He looks different, maybe bigger or maybe just pastier, and also his eyes seem to have moved a bit forward, no longer sinking into their sockets like tired bodies collapsing into a couch. He definitely hasn’t smoked today, maybe hasn’t smoked in some time. I wonder how I didn’t notice this change on the phone. He gives my shoulder a squeeze. “It’s good to see you, Dale,” he says.

In Petey’s living room, over a beer that goes to my head like I’m pubescent, I talk about Cheeky. The room is as stripped as it’s always been: tall white walls, no furniture except the worn-out sofa we’re sitting on, not even a coffee table for our beer bottles. But looking around, I do notice one new thing, a strange thing: a small plant on the windowsill. If I didn’t know better, I’d think a woman got Petey this plant, but he’d have told me if he was dating. I try to explain why in one sharp moment I had to leave the psych ward. I say “psych ward” when I talk to Pete, but it’s not an accurate name for the place that’s been my home in the last few months; no name feels accurate. Cheeky always says “the institute,” which I can’t bring myself to say. When I stop talking, Petey is looking at me like he’s a detective working a case and I’m one of the suspects. I know that look; it means he’s trying to gauge if I can take what he has to say. He’s probably had that look for some time, but I kept my eyes on the floor or the plant the whole time I was talking. Now I’m looking straight at him, but he still seems unsure, so I have to verbalize. “Hit me,” I say. He nods. Then he says, “You’re an asshole.” This makes me laugh even though I know Pete isn’t joking. “I’m serious,” he says. I say, “How am I an asshole?” Pete says, “Dale, crawl outside your own ass for one minute and think.” I look at him, then I look away like I’m thinking, then I shake my head, quick gestures, the kind where if you do them too long, people think it’s a seizure. I suppose I’m trying to communicate something like Fuck if I know! without using the actual words, which for some reason I can’t locate. “Pete, I know the moment she was talking about, okay? I’m not an idiot. I just don’t get why it was so wrong to say what I said.” I can’t read Pete’s eyes in this moment, but I know I don’t like what I’m seeing. Still, I say the thing I didn’t dare say to Cheeky earlier, not because it’s a lie—it isn’t—but because I feared her response in a way that I don’t with Petey, in a way that you never do with blood. “I gave her a fucking compliment,” I say, “someone else would have said thank you.” Petey chuckles. “You’re fucked in the head, D.,” he says. I say, “Well, then it’s good I’m in the loony bin,” and we laugh. It’s a nice moment. Petey’s laughter is open and deep. I look at him and I see that he loves me the same whether I’m an asshole or a saint. This thought makes me tear up. I close and open my eyes a couple of times to dry up the tears without touching my face. “I care about this girl, Petey,” I say. I start to explain something about Talie, but I stop myself. Instead I say, “I haven’t felt this way in a long time.” Petey nods and takes a swig. Then he nods again. “Then you gotta show her you get it,” he says, “none of this compliment shit.” “Okay,” I say. The problem with showing Cheeky I get it is that I don’t really get it, and Petey can see this problem on my face. “Thinking you’re awesome for finding someone attractive is one of those things,” he says, “like a logic loop?” I stare at him. “The fact you’re celebrating this proves there’s nothing to celebrate,” he says. “But there is!” I say. Pete shakes his head. “Think of it this way, Daley,” he says. “If this girl said to you, ‘You know, I never imagined I could be attracted to a dude with such a tiny dick, but I’ve really grown as a person, so now I don’t mind,’ would you feel . . . complimented?” I say I don’t think it’s the same at all. I say it’s a ridiculous example, considering my girth. And then I say thank you. I say I get it now. “Do your thing,” Petey says, because he can tell I’m suddenly itching to head back. “Glad I could help.”

On my way out I say, “So, what, you into greenery now?” I point with my chin toward the plant. “Oh, that?” Pete says. “My sister got it for me.” “Mel’s talking to you!?” I say. Pete chuckles. “Guess she decided to believe the whole thing wasn’t our fault,” he says, “or maybe once her douchebag was out of the picture, she figured better to lose money than lose money and your brother.” I know it’s my turn to laugh now, but I can’t laugh. “She forgave you,” I say, “Mel forgave you.” “Yeah,” he says. “I suppose she did.” I look at Petey. “This makes me want to cry,” I say. “Don’t cry,” he says. “It feels like we’re going to be okay,” I say, like there’s not gonna be a trial. “I really don’t think this proves that,” he says. “I’m so happy I came here today,” I say. I can see now that we’re both starting a new chapter. I give him a hug. Going down the stairs, I shout to him, “There’s still hope for us, Petey!”

Entering the institution is much easier than exiting was, much less dramatic. I walk in like I went out for groceries and the store was closed. “Hey, Reviva,” I say. She looks up. Her hair is a funny color, something between purple and blue, and I wonder how I never noticed before. “Did you go to the salon while I was gone?” I ask her. I’m half joking, half thinking maybe that’s what happened. Reviva looks at me with concern, so I give a quick laugh. She smiles at me and my quirky sense of humor. “Sign here, sweetie,” she says. She looks me up and down with kind eyes. “Any new acquisitions for safekeeping, sweetheart?” There’s a gray plastic box to her left where any contraband should go. Cracking a joke about a hidden gun would likely be a bad idea. It’s possible that for the rest of my life I’ll never be able to mention the word “gun” without putting people on edge, which is unfortunate, considering all the work I’ve done on myself, all the progress I’ve made. “Nope,” I say to Reviva, “nothing new.” “Good,” she says, “because you know if that thing starts beeping, it beeps for days.” She nods at the metal detector as if I’d be confused otherwise. I shake my head. “Welcome back,” she says.

I wait for the elevator, and when it doesn’t come, I remember that it’s not coming; it’s been out of order for days. The stairs to the fourth floor are a mountain, and right now, it turns out, I am a careful climber. I see myself like you would see a movie—this happens sometimes, and generally speaking, it’s not a good sign. I am still me, but I also see me. I look like a man who’s lost his gumption. I can tell: each step is costing me confidence, taking a toll of spirit. The man who left Pete’s place an hour ago was going to run to Cheeky’s room so fast he’d feel the strain in his muscles. He knew how it would all play out: she would notice the change right away—something in the man’s eyes, something in his shoulders—and she would hug him. But as she hugged him, her arms would be soft, cautious, because she wouldn’t be ready to forgive him, not yet. But then the man—because he felt something for her that wasn’t bigger or stronger, precisely, than what he felt for Talie, but different, more centered, the feeling of getting back on the hiking trail after a long roundabout through the woods—he would find the right words. Or really, the words would find him. This would happen with such ease, it would be hard to believe there was ever any hardship. He would keep it simple, the man. He would say something like: “I’m so sorry. I was a jerk. What I said had nothing to do with you and everything to do with my bullshit. You are gorgeous and I could not be more attracted to you.” When he was done saying these simple words, he would see their effect taking shape, and that shape would be the shape of the woman he loved opening up. She would take his hand, then the rest of him. They would move out of the ward eventually, of course. They would gain custody of her daughter—she has a daughter, he remembers now, whom she hardly ever mentions, but he figures that has to be important, the custody part, because what mother wants to leave the care of her child to strangers? So they would get custody. And sure, they would fight on occasion, disagree on some stuff involving finances and sometimes the laundry. Nothing is perfect. But this man and this woman, theirs would be a happy ending.

This confident man must have died on the way over and somehow I didn’t notice. Because the man I’m watching now climbing up the stairs—I mean, are you seeing what I’m seeing? The slow rhythm of his body, the bad posture? This man is going to fuck everything up, same as he did before; if he’s lucky, this time at least no one will die. When he arrives upstairs, he will exude hesitation. He’ll speak nonsense. And Cheeky, here’s what she’ll say: “I love you, Dale. But you have so much growing to do. And if I’m going to be somebody’s mama, it should be my baby girl back home, not a six-foot-tall man.” Hearing her words, the man will feel himself start to shrink: a loss of mass, a shortening of the bones, not by an ax, not by any violence. Through the physical power of memory, his body will morph back into its old form, its true form. The man—you can see this, right?—he is in fact a child. And in this moment he’ll wear the body of a child. The woman talking to him, she is enormous. Her size is her strength as much as his smallness is his weakness. What can either of them do with this truth?

The woman will see what her words have done, and maybe some part of her will wish that she’d stayed silent. She will take the child’s hand and squeeze it—gentle first, then hard. The child will move their hands toward her thigh and lean into her, waiting only for her invitation. But what kind of woman lets herself open to a child? What kind of woman allows her body to lead such a small body into herself—even if it would be just this one time, this one last time? She shakes her head. “No,” the woman says. “No, Dale. No.”

So much air is leaving my lungs when I hear this word, and at the same time new air enters, waves and waves of oxygen. I’m at the top of the stairs now, I am back inside my body, I am riding the oxygen all the way up until there is no more up ahead. Fuck all that, I think. This thought blasts like music, and for a second I think I cursed out loud. I’m a child? Me? I let out a laugh. I’ve lost the love of my life to a senseless death. I’ve expressed my anguish with a weapon and managed to hurt no one. I’ve avoided jail more than once, collected garbage at the side of the road while humming a tune. I’ve made fortunes in real estate, lost fortunes in real estate. Even at my lowest I still got my clothes dry-cleaned. I’ve broken the law, yes. Some people paid money and got no property in return, good people like Pete’s sister Mel. Even her douchebag was a good man, if I’m being honest, not someone who deserved a swindle. So yes, for my most recent mistake, I may lose my freedom. A part of me thinks that kind of payday would be just fine, offer relief. I’d make good on my moral debt with time served and be absolved, reborn. Another part of me says, Hey, Dale, if you’re your own enemy, who you think will be your champion? Every day I get out of bed and talk to both voices. I show up to group. I do the work. So say what you will about me, but I’ve lived a full life. I am a grown-ass man. And if Cheeky can’t see it, well, that must be all the sugar in her bloodstream making her thoughts a little loopy. And to that I say, her fucking loss.

___________________________________

From the collection Minor Characters, available for pre-order from Roundabout Press.