20 Literary Adaptations Disavowed by Their Original Authors

White-washing, Misquoting, Miscasting, and Other Sins of Hollywood

Filmmakers love to use novels as source material for films, and writers love to have their work adapted for the big screen. Why not? For filmmakers, literary adaptations come with a built-in fan base, along with (usually) a well-crafted story populated by ready-made, compelling characters. For writers, film adaptations come with money, prestige, and—hopefully—with more attention for the book, which often translates into more copies sold. Plus, sometimes you get to meet famous people. (That said, not every book should actually be made into a movie.) But sometimes Hollywood can be more trouble than it’s worth. Just ask these twenty authors, who all hated the film adaptations of their literary works—for reasons ranging from the understandable to the, well, let’s say enigmatic. I mean, artists, am I right?

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975)

Based on: Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962)

In the 1960s, Kirk Douglas bought the rights to Kesey’s cult novel and turned it into a Broadway play, casting himself as McMurphy. He wanted to turn the play into a film, too, but couldn’t get any traction until his son, Michael Douglas, took the reins. Michael found director director Miloš Forman and wrote a first pass at a screenplay—but originally, they wanted Kesey to be involved. As he described it:

My producing partner, Saul Zaentz—the owner of Fantasy Records and a voracious reader—felt an affinity with Kesey. After Larry and I made a first attempt, Saul asked Kesey to write a screenplay and promised him a piece of the action. But like a lot of novelists trying to adapt their own material, it didn’t work out. We fell out with him after that. It was our only longstanding, painful issue. We got in to a financial dispute—it was silly, but maybe it was his way of defending his ego.

According to director Miloš Forman’s website, Kesey’s main problem was that the film wouldn’t be told from Chief Bromden’s perspective. In the end, as the legend goes, Kesey never saw the movie—though he did come across it one day while he was channel-surfing. His response? He promptly switched to the next station.

Earthsea (2004)

Earthsea (2004)

Based on: Ursula K. Le Guin, Earthsea cycle (1968-2001)

Le Guin hated the Sci-Fi Channel’s adaptation of her books, and she had quite a lot to say on the subject, but the biggest problem was that the miniseries completely whitewashed the original text. Early on, she was consulted (somewhat) but when she raised objections, they told her that shooting had already begun. “I had been cut out of the process,” she wrote at Slate.

And just as quickly, race, which had been a crucial element, had been cut out of my stories. In the miniseries, Danny Glover is the only man of color among the main characters (although there are a few others among the spear-carriers). A far cry from the Earthsea I envisioned. When I looked over the script, I realized the producers had no understanding of what the books are about and no interest in finding out. All they intended was to use the name Earthsea, and some of the scenes from the books, in a generic McMagic movie with a meaningless plot based on sex and violence.

Most of the characters in my fantasy and far-future science fiction books are not white. They’re mixed; they’re rainbow. In my first big science fiction novel, The Left Hand of Darkness, the only person from Earth is a black man, and everybody else in the book is Inuit (or Tibetan) brown. In the two fantasy novels the miniseries is “based on,” everybody is brown or copper-red or black, except the Kargish people in the East and their descendants in the Archipelago, who are white, with fair or dark hair. The central character Tenar, a Karg, is a white brunette. Ged, an Archipelagan, is red-brown. His friend, Vetch, is black. In the miniseries, Tenar is played by Smallville‘s Kristin Kreuk, the only person in the miniseries who looks at all Asian. Ged and Vetch are white.

My color scheme was conscious and deliberate from the start. I didn’t see why everybody in science fiction had to be a honky named Bob or Joe or Bill. I didn’t see why everybody in heroic fantasy had to be white (and why all the leading women had “violet eyes”). It didn’t even make sense. Whites are a minority on Earth now—why wouldn’t they still be either a minority, or just swallowed up in the larger colored gene pool, in the future?

“I live in a racially bigoted country,” she wrote in Locus. “From the start, I saw my Earthsea as a deliberate refusal to go along with the prejudice that sees white as the norm, and the fantasy tradition that accepts the prejudice. . . I want to say that I am very sorry for the actors. They all tried really hard. I’m not sorry for myself, or for my books. We’re doing fine, thanks. But I am sorry for people who tuned in to the show thinking they were going to see something by me, or about Earthsea. I will try to be more careful in future, and not let either myself or my readers be fooled.”

She was also very irritated when the director, in an interview, claimed that he had been “very, very honest to the books,” and explained that “The final moments of the film culminate in the union of all that and represent two different belief systems in this world, and that’s what Ursula intended to make a statement about. The only thing that saves this Earthsea universe is the union of those two beliefs.” By no means did she intend to make such a statement. “Had “Miss Le Guin” been honestly asked to be involved in the planning of the film,” Le Guin wrote, “she might have discussed with the film-makers what the books are about. . . I wonder if the people who made the film of The Lord of the Rings had ended it with Frodo putting on the Ring and ruling happily ever after, and then claimed that that was what Tolkien “intended…” would people think they’d been “very, very honest to the books”?”

Myra Breckinridge (1970)

Myra Breckinridge (1970)

Based on: Gore Vidal, Myra Breckinridge (1968)

“Myra Breckinridge,” Vidal said, “is in many ways considered the worst film ever made—for which I often get credit, though I had nothing to do with it.” In a 1977 interview with critic Hollis Alpert, Vidal blames him, saying that the film adaptation of his controversial and bestselling novel was “not just a bad movie, it was an awful joke.”

I have you, Mr. Alpert, to thank for that. You once reviewed a film called Joanna, made by an English pop singer named Michael Sarne. This film was like fifty-two Salem commercials run back-to-back—people running in slow motion through Green Park, girls with long hair, and lots of plummy dialogue. Anyway, you must have suffered a sudden lapse, because your judgements are usually impeccable. Richard Zanuck and David Brown, who were then running Twentieth Century-Fox, suddenly asked me to see Joanna, and I knew something was up. I looked at what I thought was one of the ten worst films. The next thing I knew they said, “Well, he’s directing Myra Breckinridge, and he will also write the script.” I said, “What has he done to justify giving him a major film to direct, a movie about Hollywood, a town he has yet to visit?” They said, “Joanna is a great flick.” I said, “It’s a terrible picture.” They said, “Just look at what the critics say.” And there was the Hollis Alpert review. Seared on my memory is that review. I said, “What about the other reviewers?” They said, “What difference do they make? He’s the best.” Anyway, Michael Sarne never worked in films after Myra Breckinridge. I believe he is working as a waiter in a pub in London where they put on shows in the afternoon. This is proof that there is a God and, in nature, perfect symmetry.

To be fair, Vidal also tells Alpert that he hasn’t even liked any of the movies made from his screenplays, never mind his novels, which never quite lived up to what he had in mind. There’s just no satisfying some people.

Mary Poppins (1964)

Mary Poppins (1964)

Based on: P. L. Travers’s Mary Poppins (1934)

When the credits rolled at the 1964 world premiere of Walt Disney’s Mary Poppins, twelve hundred people gave the film a five-minute standing ovation. Everyone loved it—except P. L. Travers, who sat right through that ovation, weeping. “Anyone,” wrote Caitlin Flanagan in the New Yorker, “could have been forgiven for assuming that her tears were the product either of artistic delight or of financial ecstasy (she owned five per cent of the gross; the movie made her rich). Neither was the case. The picture, she thought, had done a strange kind of violence to her work.

The première was the first Travers had seen of the movie—she did not initially receive an invitation, but had embarrassed a Disney executive into extending one—and it was a shock. Afterward, as Richard Sherman recalled, she tracked down Disney at the after-party, which was held in a giant white tent in the parking lot adjoining the Chinese Theatre. “Well,” she said loudly. “The first thing that has to go is the animation sequence.” Disney looked at her coolly. “Pamela,” he replied, “the ship has sailed.” And then he strode past her, toward a throng of well-wishers, and left her alone, an aging woman in a satin gown and evening gloves, who had travelled more than five thousand miles to attend a party where she was not wanted.

Biographer Valerie Lawson wrote that it took Travers a while to begin really speaking out against the film, however much she disliked it. According to Lawson, Travers “told a contributor to The New York Times that the movie went against the grain of the books, that it was merely a colorful extravaganza, as far from true magic as it was possible to be.” She said the character of Bert ruined the film—and she also said he couldn’t quote her. In 1968, she wrote: “All that smiling, just like Iago. And it was so untrue—all fantasy and no magic.”

In 2003, there was a film about the development of Mary Poppins called Saving Mr. Banks, starring Emma Thompson as P. L. Travers and Tom Hanks as Walt Disney. It got some good reviews, but—though I haven’t seen it—it sounds like it’s kind of a problematic mess, erasing Travers’s queerness (and whole personality), and making a case for Disney as the hero (which he, um, really doesn’t seem to have been).

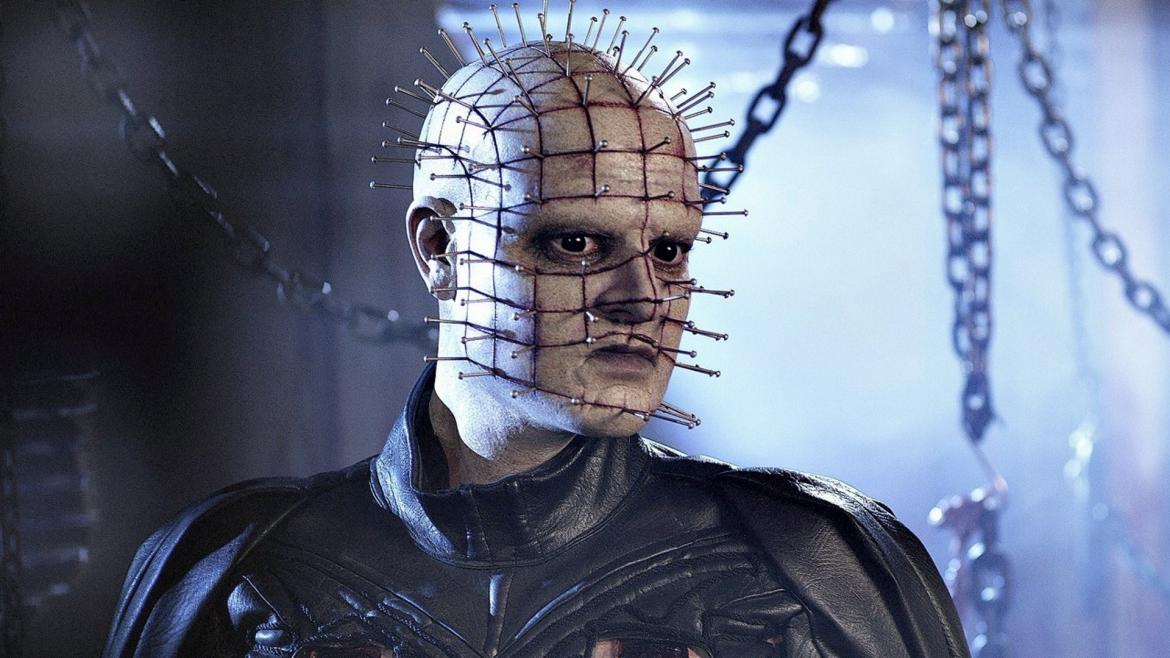

Hellraiser: Revelations (2011)

Hellraiser: Revelations (2011)

Based on: Clive Barker’s The Hellbound Heart (1986)

The fact that Clive Barker’s 1986 horror novella The Hellbound Heart has spawned ten (10) movies is, frankly, astounding. Barker himself wrote and directed the first movie, to glowing reviews in the UK and fairly soggy ones in America—but it has since become a horror classic on both sides of the pond. The many spin-offs have had varying levels of success, but the ninth one (the second to last—the tenth just came out this month) was apparently very, very bad.

It was so bad that on Twitter, Barker wrote this: “Hello, my friends. I want to put on record that the flic out there using the word Hellraiser IS NO FUCKIN’ CHILD OF MINE! I have NOTHING to do with the fuckin’ thing. If they claim its from the mind of Clive Barker, it’s a lie. It’s not even from my butt-hole.”

Fair enough.

A Wrinkle in Time (2003)

A Wrinkle in Time (2003)

Based on: Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time (1962)

We’re all very excited for the 2018 adaptation of Madeleine L’Engle’s wonderful children’s classic, but most of us have conveniently forgotten that there was already a 2003 version—originally produced as a two-part miniseries but eventually aired as a made-for-tv film. L’Engle was 85 at the time, and expressed her feelings in an interview with Newsweek:

So you’ve seen the movie?

I’ve glimpsed it.

And did it meet expectations?

Oh, yes. I expected it to be bad, and it is.

I expect the new one to do much better justice to her story.

My Foolish Heart (1949)

My Foolish Heart (1949)

Based on: J. D. Salinger’s “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut” (1948)

This is the only authorized adaptation of any of Salinger’s works—and what a work they chose: a short story that’s nearly all dialogue and really isn’t enough fodder for a film. Perhaps that’s why they had to pad it up so much. “To say that Hollywood took liberties with “Uncle Wiggily” when devising My Foolish Heart would be an understatement,” biographer Kenneth Slawenski wrote in J. D. Salinger: A Life. “A story crafted by Salinger as an exposé of suburban society and a call to personal examination was twisted by Hollywood into a love story that oozed sentimentality.” In Salinger, David Shields and Shane Salerno’s “oral biography” of Salinger, A. Scott Berg reports that “Salinger’s response to My Foolish Heart was extremely violent,” and Jean Miller says:

I remember his spouting off about Hollywood. I think he had just seen My Foolish Heart and was fit to be tied. He was furious. And that pretty much took up that evening because he was furious. He didn’t understand how intelligent people—of course he’d decided that once you hit the California border there wasn’t a brain left—but how anybody could take his story and make such sentimental has out of it. He felt it had nothing to do with this story, which of course had such a different message. It was trash, and he didn’t want anything to do with it.

Berg confirms: “I think he was probably embarrassed and humiliated by the movie.” But in a letter excerpted in Salinger, the novelist writes to Paul Fitzgerald (August 26, 1949):

If you’re interested in movies—and I hope you’re not—an old story of mine, called UNCLE WIGGLY IN CONNECTICUT is being released pretty soon under the title of MY FOOLISH HEART. Two brothers named Epstein bought the story and wrote a screenplay out of it. I haven’t seen it, but from what I’ve heard they’ve loused it up nicely. My own fault. Money’s the root of you-know-what.

However, while popular legend would have it that it was Salinger’s disgust with My Foolish Heart that caused him to refuse any more dealings with Hollywood, both Salerno and Slawenski assure us this is a myth. “In actuality, while Salinger seemingly was working to keep the world away,” Salerno writes, “he was eagerly engaged in a secret film collaboration with television writer and producer Peter Tewskbury.” Tewskbury wanted to adapt “For Esmé—with Love and Squalor.” Salinger agreed, under one condition: that he be able to cast the role of Esmé personally. Tewskbury accepted, and began working on the script, sending drafts back to Salinger (apparently Salinger kept undoing any changes Tewskbury made, returning the drafts so they were as originally written), but when he finally met the writer’s choice for Esmé, a friend’s thirteen-year-old daughter, he balked. “She’s too old,” he told his wife Cielle. “She is past that delicate moment that makes the miracle of Esmé. And if I cast this young woman in the role, I would be destroying the beauty of Salinger’s work, and I won’t do that.” He called it off.

Charlotte’s Web (1973)

Charlotte’s Web (1973)

Based on: E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web (1952)

There’s a reason it took twenty years to adapt E. B. White’s beloved children’s book—he was nervous about what Hollywood would do to it. “Anybody who can’t accept the miracle of the web,” he reportedly wrote to his agent, “shouldn’t try to film it.” In 1967, he entered negotiations with a production team, John and Faith Hubley, and wrote to his lawyer:

I want the chance to edit the script wherever anything turns up that is a gross departure or a gross violation. I also would like to be protected against the insertion of wholly new material—songs, jokes, capers, episodes. I don’t anticipate trouble of this sort; the Hubleys have already expressed to me in a letter (as well as verbally) their desire to produce a faithful adaptation, and I believe them to be sincere in this. . . I will give you an example of what I call a “gross” violation. In my book, Charlotte dies. If, in the screenplay, she should turn up alive at the end of the story in the interests of a happier ending, I would consider this a gross violation, and I would regard my disapproval as reasonable.

That deal fell through, but eventually Hanna-Barbera bought the rights—I assume without giving White any of the editorial oversight he wanted, though Charlotte does, of course, die.

“The movie of Charlotte’s Web is about what I expected it to be,” he wrote to a friend after the film’s release. “The story is interrupted every few minutes so that somebody can sing a jolly song. I don’t care much for jolly songs. The Blue Hill Fair, which I tried to report faithfully in the book, has become a Disney World, with 76 trombones. But that’s what you get for getting embroiled in Hollywood.”

In 1977, White’s wife wrote to Gene Deitch, a director who had been attached earlier in the adaptation process but had nothing to do with the Hanna-Barbera movie: “We have never ceased to regret that your version of Charlotte’s Web never got made. The Hanna-Barbera version has never pleased either of us. . . a travesty.” In 1978, White himself wrote to Deitch to say that “the whole episode, the attempt to make a film of Charlotte’s Web, is one of my nightmares. The only good thing to come out of it for me was that I learned never to try anything like that again.”

Solaris (1972, 2002)

Solaris (1972, 2002)

Based on: Stanisław Lem’s Solaris (1961)

Stanisław Lem didn’t particularly care for either of the mainstream adaptations of his wonderful science fiction novel (about astronauts who discover a planet with a sentient sea—read it!). Of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 attempt, Lem wrote:

I have fundamental reservations to this adaptation. First of all I would have liked to see the planet Solaris which the director unfortunately denied me as the film was to be a cinematically subdued work. And secondly—as I told Tarkovsky during one of our quarrels—he didn’t make Solaris at all, he made Crime and Punishment. What we get in the film is only how this abominable Kelvin has driven poor Harey to suicide and then he has pangs of conscience which are amplified by her appearance; a strange and incomprehensible appearance. This phenomenalistics [sic] of Harey’s subsequent appearances was for me an exemplification of certain concept which can be derived almost from Kant himself. Because there exists the Ding an sich, the Unreachable, the Thing-in-Itself, the Other Side which cannot be penetrated. But in my prose this was made apparent and orchestrated completely differently . . . I have to make it clear, however, that I haven’t seen the whole film except for 20 minutes of the second part although I know the screenplay very well because Russians have a custom of making an extra copy for the author.

And what was just totally awful, Tarkovsky introduced Kelvin’s parents into the film, and even some Auntie of his. But above all the mother—because mother is mat’, and mat’ is Rossiya, Rodina, Zemlya. [Russia, Motherland, Earth] This has made me already quite mad. At this moment we were like two horses pulling the carriage in opposite directions.

. . .

The whole sphere of cognitive and epistemological considerations was extremely important in my book and it was tightly coupled to the solaristic literature and to the essence of solaristics as such. Unfortunately, the film has been robbed of those qualities rather thoroughly. Only in small bits and through the tracking camera shots we discover the fates of those present at the station but these fates should not be any existential anecdote either but a grand question concerning man’s position in Cosmos, etc.

My Kelvin decides to stay on the planet without any hope whatsoever while Tarkovsky created an image where some kind of an island appears, and on that island a hut. And when I hear about the hut and the island I’m beside myself with irritation. . . This is just some emotional sauce into which Tarkovsky has submerged his heroes, not to mention that he has completely amputated the scientific landscape and in its place introduced so much of the weirdness I cannot stand.

But at least he had some say with Tarkovsky—unlike when the film was remade in America. When Steven Soderbergh remade the film in 2002, he made it clear that he was aiming not to re-do Tarkovsky’s job but to create an entirely new adaptation of Lem’s novel. “Well, I’m a big fan of Tarkovsky,” he said in an interview. “I think he’s an actual poet, which is very rare in the cinema. The fact that he had such an impact with only seven features, I think is a testament to his genius. I really loved the film. I didn’t feel his film could be improved upon. I really just had a very different interpretation of the Stanisław Lem book, which has a lot of ideas in it, enough I think to generate a couple more films.”

So what did Lem think about this “very different interpretation”? “Some reviewers, like the one from the New York Times, claim the film was a “love story,” he wrote,

a romance set in outer space. I have not seen the film and I am not familiar with the script, hence I cannot say anything about the movie itself except for what the reviews reflect, albeit unclearly—like a distorted picture of one’s face in ripply water. However, to my best knowledge, the book was not dedicated to erotic problems of people in outer space.

. . .

The book ends in a romantic‑tragic way; the girl herself wished to be annihilated, not wanting to be an instrument with the help of which the one she truly loves is being studied by some unknown power. Her annihilation takes place unbeknownst to Kelvin—with the help of one of Space Stations’ residents. The Soderbergh movie supposedly has a different, more optimistic finale. If this were the case this would signify a concession to the stereotypes of American thinking regarding science fiction. It seems that these deep, concrete ruts of thinking cannot be avoided: either there is a happy ending or a space catastrophe. This may have been the reason for the touch of disappointment in some of the critics’ reviews—they expected the girl created by the ocean to turn into a fury, a witch or a sorceress who would devour the main character, while worms and other filth would crawl out of her intestines.

. . .

Summing up, as Solaris‘s author I shall allow myself to repeat that I only wanted to create a vision of a human encounter with something that certainly exists, in a mighty manner perhaps, but cannot be reduced to human concepts, ideas or images. This is why the book was entitled Solaris and not Love in Outer Space.

This one gets extra points for all the fun he makes of American movies (and movie reviewers).

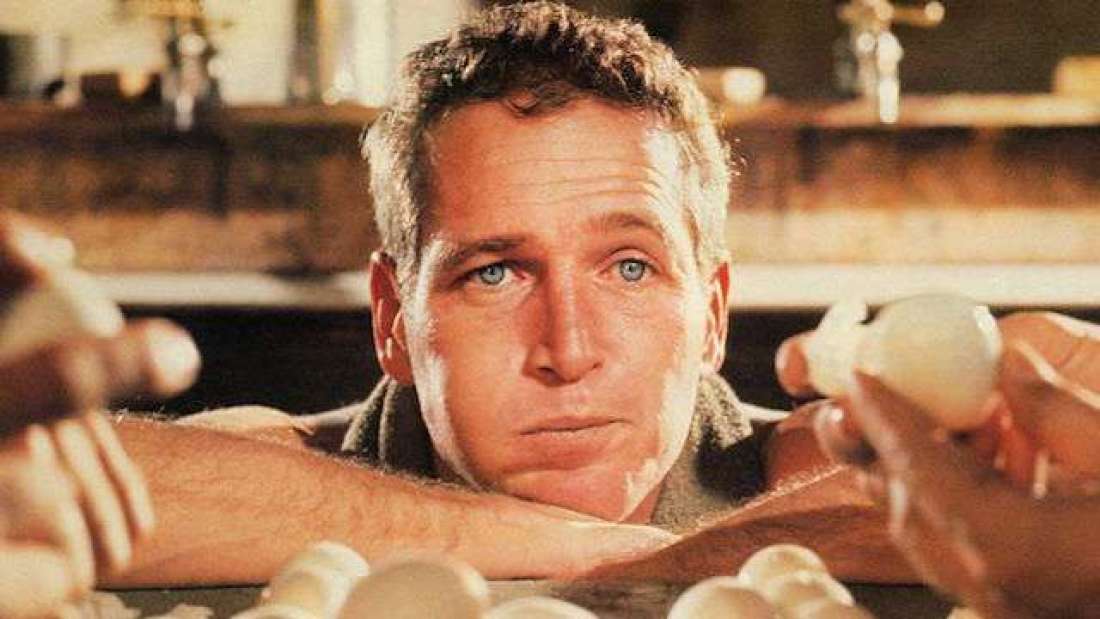

Cool Hand Luke (1976)

Cool Hand Luke (1976)

Based on: Donn Pearce’s Cool Hand Luke (1965)

It’s a little known fact that the classic Paul Newman flick Cool Hand Luke is based on a novel—and an even littler-known fact that the author of that novel, ex-burgular, safecracker, and counterfeiter Donn Pearce, who spent two years on a Florida chain gang and wrote the book about his experiences, didn’t like it much.

“They did a lousy job and I disliked it intensely,” he told the Telegraph. What about Paul Newman, they asked him, whom just about everybody loves? “Not me,” Pearce said. “The guy was so cute looking. He was too scrawny. He wouldn’t have lasted five minutes on the road.”

Pearce also co-wrote the screenplay for the movie, and even got a small part. “[Newman and I] spoke a bit on set, but not much,” he said. “He even asked me to dinner, then cancelled when his PR people realised that he didn’t need to be seen eating with an ex-con. I didn’t like the guy. I didn’t like that whole Hollywood crowd, I was never made welcome.”

Pearce also hates the movie’s most famous line (ranked, in fact, by the American Film Institute as the 11th greatest movie quote of all time): “What we got here is failure to communicate.” A prison warden like that, Pearce told the Telegraph, would never use the word “communicate.”

The Last Man on Earth (1964)

The Last Man on Earth (1964)

Based on: Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend (1954)

Everything started well enough: in 1958 Hammer Films approached Matheson to write a script for a film adaptation of I Am Legend. He did so, calling it Night Creatures, but then, as he explained in an interview,

I was told that the censor wouldn’t pass it because it was too horrible. I didn’t believe it at first but, later, I was convinced that this was true. . . Val Guest was going to direct it. When it was brought to the United States, I was told that Fritz Lang was going to direct it. Unhappily, this did not eventuate. I believe that my script for Hammer was faithful to the book. I never choose to do otherwise. If a book is interesting enough to buy for a movie, why not present it as is instead of constantly changing it?

By the time the movie was finished, it had been rewritten so much that Matheson took his name off the project—he is credited as “Logan Swanson.”

“I was disappointed in The Last Man on Earth,” Matheson said in another interview, “even though they more or less followed my story. I think Vincent Price, whom I love in every one of his pictures that I wrote, was miscast. I also felt the direction was kind of poor. I just didn’t care for it.” (Elsewhere he has wished for Harrison Ford in the main role.) He didn’t care for the second attempt at adapting I Am Legend, either. “The Omega Man was so removed from my book that it didn’t even bother me!” he said. “I was told at one time that Charlton Heston had managed to interest Sam Peckinpah in directing. That could have really been something special.” Ironically, The Last Man on Earth is widely considered to be the most faithful adaptation of the three (three!) made. But Matheson was still unsatisfied. “I don’t think a faithful adaptation will ever be made,” he said. “It can be but it won’t.”

I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997)

I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997)

Based on: Lois Duncan’s I Know What You Did Last Summer (1973)

I know what you didn’t do last summer: realize that this classic ’90s slasher was based on a novel. In a Q&A included in the back of a 2010 edition of the book, Duncan explained that she had nothing to do with the production of the movie—”They kept me as far away as possible,” she said. “I think they were afraid of how I might react if I realized what my little masterpiece was going to turn into.”—and called the finished product a “shock.”

I went to the theater bought my ticket and popcorn, and found a seat. Then onto the screen came an insane fisherman carrying an ice hook. He wasn’t in my book. I thought, You know, this is a big complex; maybe I’ve walked into the wrong theater. So I was preparing to leave and then, no, up from below rolled the words “I Know What You Did Last Summer,” and I thought, That is my book, but who is that man and what is he going to do with that ice hook? Well, I soon found out. He was going to decapitate my characters. Their heads were flying off, and their blood was spurting, and everybody was screaming, and I was screaming. I was so horrified I couldn’t even open my popcorn.

“I had expected it to be my story,” she went on, “and it wasn’t. It was my characters and my plot gimmick, but then it went in all directions. Even the double-identity twist, which was the crux of the story, had been omitted.” But it was actually even worse than that: she had a real problem with the intensity of the “sensationalized violence,” and not because of any kind of authorial vanity. She explains that “several years ago my own teenage daughter, Kait, had been chased down in her car and shot to death, and I had seen, right in front of my eyes, what real violence is. To have people screaming and laughing about it did not go down well. . . if you’ve known it in real life, then seeing it portrayed like that on the screen is a travesty.”

American Psycho (2000)

American Psycho (2000)

Based on: Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991)

Bret Easton Ellis has said that he doesn’t think the iconic adaptation of American Psycho “really works as a film. The movie is fine, but I think that book is unadaptable because it’s about consciousness, and you can’t really shoot that sensibility.” Plus, he said, a film adaptations requires clarity about whether Patrick Bateman’s murders were all in his head or not—something the novel leaves ambiguous. “A movie automatically says, “It’s real.” Then, at the end, it tries to have it both ways by suggesting that it wasn’t,” Ellis said in another interview. “Which you could argue is interesting, but I think it basically confused a lot of people, and I think even Mary [Harron, the director] would admit that.”

Okay, so it’s an issue of craft. Fair enough, except that Ellis also has a well-documented problem with female directors—and American Psycho was directed by a woman, the aforementioned Mary Harron, whose work he, in that same interview, said he is only convinced by “to a degree”. “There’s something about the medium of film itself that I think requires the male gaze,” Ellis went on.

We’re watching, and we’re aroused by looking, whereas I don’t think women respond that way to films, just because of how they’re built. . . I think it’s a medium that really is built for the male gaze and a male sensibility. I mean, the best art is made under not an indifference to, but a neutrality [toward] the kind of emotionalism that I think can be a trap for women directors. But I have to get over it, you’re right, because so far this year, two of my favorite movies were made by women, Fish Tank and The Runaways. I’ve got to start rethinking that, although I have to say that a lot of the big studio movies I saw last year that were directed by women were far worse than the shitty big-budget studio movies that were directed by men.

So does he really think American Psycho is unadaptable, or does he just think it’s unadaptable by a woman?

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Based on: Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange (1962)

At first, according to Robert Hofler’s book Sexplosion, Anthony Burgess rather liked Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of A Clockwork Orange.

Watching the completed film, Burgess didn’t hold it against Kubrick when his wife, repulsed by its choreographed sex and violence, asked to leave the screening room after a mere ten minutes. Initially, he even managed to tell the press, “This is one of the great books that has been made into a great film.” Maybe he meant what he said. Or maybe he simply wanted to persuade Kubrick to direct his screenplay Napoleon Symphony.

But things went south when the film’s violence began to attract criticism, and Burgess felt that Kubrick had left him holding the bag. “I was not quite sure what I was defending,” Hofler quotes Burgess saying, “the book that had been called “a nasty little shock” or the film about which Kubrick remained silent. I realized, not for the first time, how little impact even a shocking book can make in comparison with a film. Kubrick’s achievement swallowed mine, whole, and yet I was responsible for what some called its malign influence on the young.”

In the end, according to Hofler, Burgess wound up hating the film. “Or Kubrick. Or both. A decade later when he adapted his novel for the stage, he made sure to include the following stage direction: “A man bearded like Stanley Kubrick comes on playing, in exquisite counterpoint, ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ on a trumpet. He is kicked off the stage.”

The Shining (1980)

The Shining (1980)

Based on: Stephen King’s The Shining (1977)

Just to pile on Stanley Kubrick (ah, he can take it): Stephen King notoriously hates his adaptation of The Shining. I don’t even know how King even has time to watch all of his adaptations, let along have opinions about them, but that’s really neither here nor there. King thought Kubrick’s version was “Too cold. No sense of emotional investment in the family whatsoever on his part,” as he told The Paris Review.

I felt that the treatment of Shelley Duvall as Wendy—I mean, talk about insulting to women. She’s basically a scream machine. There’s no sense of her involvement in the family dynamic at all. And Kubrick didn’t seem to have any idea that Jack Nicholson was playing the same motorcycle psycho that he played in all those biker films he did—Hells Angels on Wheels, The Wild Ride, The Rebel Rousers, and Easy Rider. The guy is crazy. So where is the tragedy if the guy shows up for his job interview and he’s already bonkers? No, I hated what Kubrick did with that.

King had written a screenplay for The Shining, but Kubrick didn’t use it—it became the basis for the 1997 miniseries. “I doubt Kubrick ever read it before making his film,” King said.

He knew what he wanted to do with the story, and he hired the novelist Diane Johnson to write a draft of the screenplay based on what he wanted to emphasize. Then he redid it himself. I was really disappointed.

It’s certainly beautiful to look at: gorgeous sets, all those Steadicam shots. I used to call it a Cadillac with no engine in it. You can’t do anything with it except admire it as sculpture. You’ve taken away its primary purpose, which is to tell a story. The basic difference that tells you all you need to know is the ending. Near the end of the novel, Jack Torrance tells his son that he loves him, and then he blows up with the hotel. It’s a very passionate climax. In Kubrick’s movie, he freezes to death.

Can’t argue with that.

Das Boot (1981)

Das Boot (1981)

Based on: Lothar-Günther Buchheim’s Das Boot (1973)

Buchheim, who had been part of a propaganda unit in WWII, taking photos of U-boats, wrote the novel that inspired this legendary film—and later, when several attempts at adaptation had failed, even wrote a script for it, though that script was rejected for its length (ha, ha). The novelist expressed displeasure with the final film, directed by Wolfgang Petersen, in a 1981 essay. Now bear with me, because I don’t speak German, and can’t find this translated in full in English anywhere. But according to Google translate—and I hope this is more than translation found-poetry— he says he was treated, as most authors are by producers, as a “disenfranchised fabric supplier.” He calls the American script a “nasty falsification of my novel.” “My film, which was not filmed,” he wrote, “should have had the breath and power of a Greek tragedy. What happened instead was a cheap, shallow American action flick.” (Another rough translation, with help from Wikipedia—but you get the idea.)

The NeverEnding Story (1984)

The NeverEnding Story (1984)

Based on: Michael Ende’s The Neverending Story (1979)

And now to pick on Wolfgang Petersen some more! He later adapted another famous German novel, Michael Ende’s elaborate fantasy The Neverending Story—and he spent $25 million to do it, which made it the most expensive German production up to that point. But at least one person did not find it very magical—or worth the money. Michael Ende called the movie “revolting,” and said “The makers of the film simply did not understand the book at all. They just wanted to make money.” He and Petersen had originally collaborated on the script, but according to Ende, it was changed without his approval. “I saw the final script five days before the premiere and only as a result of a judicial verdict in Munich,” he said. “I was horrified. They had changed the whole sense of the story. Fantastica reappears with no creative force from Bastian. For me this was the essence of the book.” But that wasn’t all. “The Sphinxes are quite one of the biggest embarrassments of the film,” he said. “They are full-bosomed strippers who sit there in the desert.” After seeing a preview, he called it “a humongous melodrama of kitsch, commerce, plush and plastic. . . a cross between E.T. and The Day After.” He took his name off the film and, according to his website, “requested that those scenes that contradicted the inner logic of the story should be cut from the final take.” Petersen did not do so. Ende took out an injunction against the production company, but lost. At that point, according to Ende’s website:

Ende was left physically and mentally drained by the wrangles over the production. In his view, the movie had been made according to purely commercial criteria, and he saw it as an attack on his integrity as a writer. The battle against the production company was a question of ‘honour’: “I would never have been able to look myself in the mirror if I lent my name to something like that. I’ve fought to the point of exhaustion. They tried to wear me down with dirty tricks, and I kicked up a fuss—but what good did it do?”

Michael Ende’s fury over the filming of The Neverending Story gradually abated. Although the disappointment remained, he looked on the episode from a more distanced perspective and took a cynical view of the legal battle. It was, he argued, entirely logical that he had failed to win the case: “According to the logic of the ruling: the original novel had undoubtedly been distorted, but since the film was aimed primarily at a younger audience, such distortions were irrelevant. Of course the truth of the matter was that sixty million dollars were at stake. The only voice of opposition came from a lone author who had evidently grown too big for his boots. After all, majority opinion deems a movie to be the pinnacle of a novelist’s success. Shouldn’t writers be grateful if directors want to film their books? In financial terms, losing the court case cost me far more than I gained from the rights. At the time I took the whole thing to heart, but these days I don’t let it get to me. I heard somewhere that Part II has been released at the cinema—I haven’t even watched the thing.”

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)

Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961)

Based on: Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958)

Famously, Truman Capote wanted Marilyn Monroe for the part of Holly Golightly in the film adaptation of his now-classic novella. As Capote explained: “I had seen her in a film and thought she would be perfect for the part. Holly had to have something touching about her . . . unfinished. Marilyn had that.” But although in a lot of ways she was perfect for the role, and though Capote claimed “she wanted it so badly that she worked up two whole scenes all by herself to play for me,” she was discouraged from accepting the part by her dramatic advisor and acting coach Paula Strasberg, who said “that she would not have her play a lady of the evening.” The role ended up going to Audrey Hepburn. “Paramount double-crossed me in every way and cast Audrey,” Capote said. But it wasn’t just the casting that bothered him. “The book was really rather bitter,” he told Playboy in 1968, “and Holly Golightly was real—a tough character, not an Audrey Hepburn type at all. The film became a mawkish valentine to New York City and Holly and, as a result, was thin and pretty, whereas it should have been rich and ugly. It bore as much resemblance to my work as the Rockettes do to Ulanova.”

The adaptation of In Cold Blood, by the way, is another story. “It’s as accurate a rendering of the book as I could have hoped,” Caote said,

with the single exception that if it were done the way I would really have liked, it would have had to be at least nine hours long. As it stands, it runs about two hours; but those two hours are verbatim from the book and brilliantly done. I cooperated fully with Richard Brooks, who directed the film and did the screenplay, and we never had the slightest disagreement. The actors who play Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, by the way, turn in remarkable performances. Even the physical resemblance is uncanny; when I first saw the boy selected to play Smith, it was as if Perry had come back from the grave.

At least Hollywood got one of his bestsellers right.

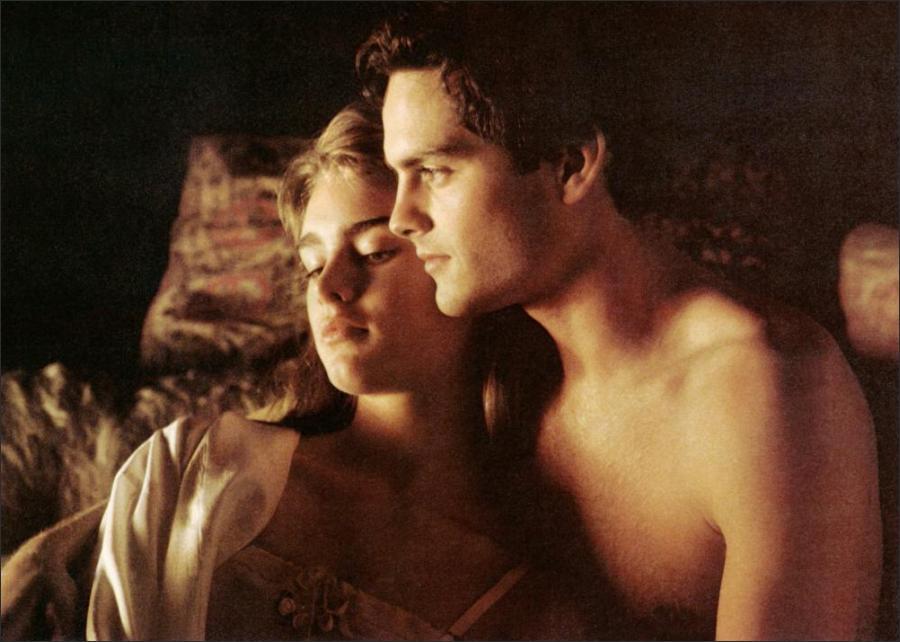

Endless Love (1981)

Endless Love (1981)

Based on: Scott Spencer’s Endless Love (1979)

Poor Scott Spencer—this happened to him twice. “Here’s what happens when Hollywood makes a really bad movie out of your novel,” Spencer wrote in The Paris Review. “You cringe, you pretend you don’t care, you laugh when they play the bad movie’s theme song at weddings you attend, and you wait for the whole thing to pass. And when it finally has, when your book has at last outlived the bad memories and associations of the first movie and it is making its leisurely literary way out in the world, without any connection to the bad movie, someone decides to make an even worse movie out of it.” That would be the 2014 remake, which Rotten Tomatoes dubbed “blander than the original Endless Love and even less faithful to the source material . . . clichéd and unintentionally silly.”

In The Hollywood Reporter Spencer called Franco Zeffirelli’s 1981 adaptation “botched—misquoted, as it were,” and in the Paris Review, wrote “I was frankly surprised that something so tepid and conventional could have been fashioned from my slightly unhinged novel about the glorious destructive violence of erotic obsession, but I’d been warned. Riding to the premiere with Zeffirelli, he reached across the expanse of his hired car and, patting my knee, said, “Scott, this movie is going to be like a knife in your heart.”” It’s safe to say Spencer agrees with Rotten Tomatoes’s assessment of the remake, in which he said his novel “seems as if it has been even more egregiously and ridiculously misunderstood.”

Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971)

Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971)

Based on: Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964)

As legend has it, this movie came to be because director Mel Stuart’s ten-year-old daughter loved Dahl’s book and asked her father to turn it into a film. Stuart, no fool, took his daughter’s advice and had Dahl himself write the screenplay. According to Dahl’s authorized biography, Storyteller, written by Donald Sturrock:

Roald eventually came to tolerate the film, acknowledging that there were “many good things” in it. But he never liked it. Even after it was acknowledged as a classic, he would dismiss it as “crummy.” He found the music trashy, attempting to cut the song “The Candyman” when the movie opened in the United Kingdom, and he loathed the director, Mel Stuart, who he felt had “no talent or flair whatsoever.” He also disliked many of the small changes to his script that had been made by David Seltzer, the young screenwriter Stuart had hired to do rewrites, believing that these had watered down “a good deal of the bite” in his own original draft. He had serious reservations about Gene Wilder’s performance as Wonka, which he thought “pretentious” and insufficiently “gay [in the old-fashioned sense of the word] and bouncy.” He regretted that the producers had chosen neither Spike Milligan nor Peter Sellers to play the role. At Roald’s request, Milligan had shaved off his beard to audition for the director, while Sellers had called Dahl personally “begging to play the part.” Both were rejected in favor of Wilder. Roald was so annoyed that, despite his own $300,000 writing fee, he considered disassociating himself entirely from the movie and “campaigning against it on TV and magazines in the US.” That was the high watermark of his rage. Eventually, as its popularity helped boost book sales, his disapproval mellowed, but he remained “enormously depressed” by the experience. It would prove his final foray into movies as a writer. From then on, as Murray Pollinger recalled, “he had no interest in working for the movies. He hated working for the movies, he hated people in the movies. Always.

Well, we already knew he wasn’t the nicest of fellows.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.