Mrs. Bobs did not know the first thing about me, for instance that I was a chalk-and-talker, recently suspended for hanging a troublesome student out of a classroom window. She did not know that I was sought by bailiffs, that I was a regular on Deasy’s Radio Quiz Show where my winnings were publicly announced each week. She did not know that I was a mess of carnal yearning and remorse, that my small weatherboard house was now legally a fire hazard, its floors and tables crammed with books and papers. A putative visitor would be compelled to travel crabwise down the hallway, between the illegal bookshelves, from front door to the sink. The kitchen table was a catastrophe, piled high with damp washing and academic quarterlies and musty pulp novels featuring Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte (“Bony”) of the Queensland Police Force.

Oh, a bookworm, she would later say.

I spent my entire life in Australia with the conviction that it was a mistake, that my correct place was elsewhere, located on a map with German names. I had lived with the expectation that something spectacular would happen to me, or would arrive, deus ex machina, and I was, in this sense, like a man crouched on a lonely platform ready to spring aboard a speeding train. I had run away from Adelaide when I should I have stayed home in the parsonage. I had married when I would have been happier single. I had fled my wife’s adultery, left the only job that ever suited me and come to Bacchus Marsh to teach the notorious second form. And still I waited for my salvation, like the pastor’s son I was, with an impatience that made my toes squirm inside my thirsty shoes. I had certainly been anticipating my new neighbours, although I could not have imagined anything like this.

The night before had been filled with awful portent. A horse float was driven past my bedroom window and two human figures then appeared. I rolled on my side, waiting for the horse to show its face but when the doors were opened nothing was revealed but kitchen chairs.

I drifted back to sleep and dreamed. In that other world I saw the doors of the float, now quilted and studded like a banquette. These swung slowly open and I saw a man and boy carry out a mattress. They staggered down the ramp, and I was slow to understand their unsteadiness was not caused by their burden but by laughter. I was sound asleep. I smiled as they danced out into the yard. They got just past the outhouse where they dropped their comic cargo beneath the walnut tree. It was only then I got the joke which was: the mattress was not a mattress. It was a huge fat snake, whiskery like a catfish, neatly folded up for travelling, wound round itself like a pastry snail. The man and boy uncoiled the serpent as if they were volunteer firefighters laying a canvas fire hose down the centre of Main Street.

Then the man charged ahead into the house holding the placid snake’s head beneath his arm. Although this man was not Mr. Deasy from the radio quiz show, he had a similar military moustache. The boy tottered helplessly behind him, holding what he could, until he collapsed onto the floor, rolling as if tickled.

For several years I had paid attention to my dreams and I judged this is a very positive specimen. I thought, while still asleep, that there was a time when snakes had feathers.

“I had lived with the expectation that something spectacular would happen to me, or would arrive, deus ex machina, and I was, in this sense, like a man crouched on a lonely platform ready to spring aboard a speeding train.”

I woke filled with light and happiness which was not ruined when I heard my complaining hens gathered outside my door. I was sorry they had been bred to be so stupid. I was sorry to keep the poor creatures waiting. I made it up to them, putting together a special treat, a pollard mix, bran, cod-liver oil, and added a good two bob’s worth of cow’s milk, stirring with my hand in the bucket. I washed. I opened the back door to find the rooster on the step. The hens must be fed first. The rooster knew that. It was his own principle, and he knew why I had to kick him across the yard. Sex is everywhere, most particularly when you have escaped it.

As I watched the chooks eat I became aware of the fuss next door, living children running through the previously abandoned house. I was in pyjamas. My feet were bare and the earth was cold. The horse float had disappeared. An extraordinary vehicle was now parked inside the cavernous open-sided shed.

I did not rush at my neighbours like a lunatic. I dressed as normal, in checked tweed gardening clothes and gumboots. I bumped the wheelbarrow off the front verandah and trundled out onto the street to collect whatever cow manure had been dropped by the beasts on their way to the sale yards. Back home, I cut a cauliflower. I collected what eggs my hens had laid for me. I took in my belt another notch. I washed the eggs and placed them in the remnants of my marriage, a chipped enamelled colander. I would not deliver this gift like a stranger, by walking down the driveway. Instead I used the vine-entangled gate in the side fence, a monument to the old friendship between a barber (whose estate owned my house) and the panelbeater who had become a landlord.

I was startled to confront a miniature boy and girl playing amongst the wild mint. They had found a fresh hen’s egg, evidence my chooks were in the habit of trespassing. Perhaps I spoke to them, perhaps not. I turned to the former panelbeater’s open-sided shed, a pavilion really, stretched across the back of the property. There, wrapped in shadow, was the vehicle: a two-tone Ford Customline. Of course I did not know the brand quite yet but it was so new and shiny that it contained an entire sky—towering white cumulus—in its bulbous fenders.

I could hear the voices of a man and woman, also the song of cooling metal.

“Hang on.”

“No, the other one.”

They might have been doing the dishes, she washing, he drying, at the kitchen sink.

I was drawn inevitably towards the automobile. I called first good morning and then coo-ee. Then I was inside the shed which had become the home of pigeons with alarming wings. Then came another awful noise, like a filing cabinet dragged across a concrete floor and there they were shooting out from under the Ford, the astonishing pair clad in faded coveralls, lying flat on mechanic’s trollies, icons with bright silver spanners in their hands.

Mister must have been five foot two and she even smaller. Missus’s hair was so tousled and curling she might have been, had not all the other evidence been so much to the contrary, a boy. Her husband’s complexion was smooth and glowing, he could have been a girl. Yet to talk of boys and girls is to miss the point. The new arrivals stared at me and I somehow understood that they, being visions, were not required to speak.

I am Willie Bachhuber, I said, for the war was less than ten years over, and it was best to get the German business finished with at once.

__________________________________

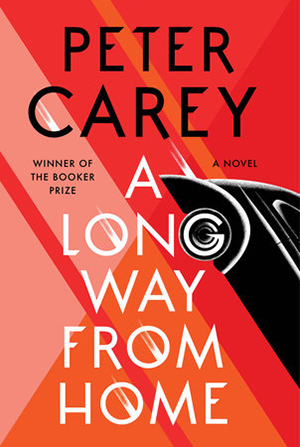

From A Long Way from Home. Used with permission of Knopf. Copyright © 2018 by Peter Carey.