11 Memoirs by 20th-Century American Radicals

Muckracking Journalists, Antiwar Activists, and More

With the Trump era now a week old and storm clouds gathering, many decent, salt-of-the-earth Americans not previously given to shows of popular unrest, never mind civil disobedience or outright violence, may find themselves newly curious about America’s radical past, in particular the radical left. For the big picture, there is always the work of the late and ever-insightful Howard Zinn, but then sometimes your curiosity craves a more intimate literature: the memoir. Perhaps you’re interested in personal transformations, or else wondering how you might hold up under the pressures of, say, a vast capitalist conspiracy, the fugitive life, or an FBI program dedicated to discrediting you and sowing discord amongst your colleagues.

The American Left—or the far left, as it’s often called these days—has not always been a marginal strand of our national discourse. Certainly it hasn’t been a docile one. In 1912, there were over 1,000 socialists holding public office in the US and at least 13 daily newspapers sympathetic to the cause. In the 1930s, trade unions were among the nation’s most powerful organizations. In the 60s, SDS strikes pulled over a million students out of classes, while civil rights marches energized a generation and changed the face of the body politic. The next decade, bombings and political violence were near daily events in some parts of the country.

Each movement produced its share of minutes and manifestoes. But then there are also the personal stories: the individual lives and journeys undergirding the cause.

For those who prefer their radical history first-hand, the 20th century provides in abundance, from the anarchist riots and unionist shutdowns of the early century to the interwar New York intellectuals, always flirting with offshoots of the Russian Revolution, to the new wave activists of the late 60s and early 70s, with the violence, infighting, despair, and a few strands of hope and inspiration that followed.

You may not like their brand of politics. Some may not go far enough for your current mood, others too far. Or perhaps the mistakes of their personal and public lives were too great to be forgiven. You may consider some of them misguided, overzealous, or criminal. Their stories—and their words—hold power all the same.

Here are eleven memoirs from 20th-century American radicals.

Revolution in Seattle, Harvey O’Connor

O’Connor was one the early century’s great muckraking, fire-breathing journalists. Revolution in Seattle, is his personal account of the 1919 general labor strike in Seattle. It was the first of its kind in the US: a great city brought to a halt while workers from all walks of life picketed, raged and organized. In the post-WWI period, there was, for a brief time, a genuine question whether the American capitalist system would continue unabated. O’Connor was one of the movement’s primary scribes: an investigative journalist, pamphleteer, and influential editor. Ultimately, he left Seattle and settled in New York as the head a leftist wire service, but he’s best remembered now for his chronicles of the robber barons and his first-hand accounts of the great anti-imperialist fights of the Pacific Northwest.

Assignment in Utopia, Eugene Lyons

Lyons makes for an odd fit. In later years he moved to the right and served as editor of that monument to conservative taste, Reader’s Digest. But as a young man, Lyons was part of the leftist intellectual set and was considered a sufficiently reliable fellow traveler that Soviet Russia gave him a warm welcome. He worked there in the late 1920s and early 30s as a correspondent for United Press. In 1930, he was the first American journalist granted an interview with Stalin. Assignment in Utopia is the story of his disillusionment with the Soviet experiment, especially the shame he felt at having turned a blind eye to Stalin’s atrocities. At times it’s heartbreaking to read Lyon’s recollections of what he and others invested in the revolution. Lyons soon turned to Trotskyism (Trotsky read Assignment in Utopia and called it “interesting, though not profound”). Eventually went so far over to the other side that he supported the activities of a newly formed radical group, the House Un-American Activities Committee. He remains one of the period’s most perplexing figures.

Revolutionary Suicide, Huey P. Newton

Originally released in 1973, Newton’s autobiography served as a chapbook for radicals during the Nixon era and beyond. Along with Bobby Seale, Newton was the co-founder of the Black Panther Party and served as Chief Ideologue. (He later took the title “Supreme Commander”; his leadership was part of what drove Assata Shakur and others from the movement.) Revolutionary Suicide is often read a manifesto, but Newton’s autobiographical details are vivid and just as powerful as the rhetoric: Oakland in the 1950s, during the Second Great Migration; the BPP’s early days at Merritt College; police brutality; the lock-up at Alameda County Jail. Brutal violence, criminal allegations, infighting and J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO would haunt Newton throughout his remaining years. His legacy seems to shift every decade, but Revolutionary Suicide remains an undeniably electric text.

Heart of the Rock, Adam Fortunate Eagle

In 1969, Adam Fortunate Eagle and Richard Oakes pulled off one of the most audacious political actions of the decade: the occupation of Alcatraz Island by a group called Indians of All Tribes. It lasted two years and while ultimately the island’s community began to unravel, the cause enjoyed tremendous support from the city’s working class and activist communities. Fortunate Eagle didn’t live on Alcatraz himself, but acted as the group’s organizer and spokesman. He’s a gifted storyteller, and besides laying out the many egregious injustices done to Indian nations, he has a way with an anecdote and a lively sense of humor. After finally cutting off power and electricity (and possibly contributing to a series of building fires), the government removed the occupiers from the island. But important policy concessions were won. The action served as a model for decades of Indian activism.

Fugitive Days, Bill Ayers & Flying Too Close to the Sun, Cathy Wilkerson

These two memoirs are best read together. Ayers and Wilkerson were members of the Weather Underground, the anti-war counterculture group famous for its white middle-class membership and a bombing campaign aimed at government buildings. Ayers is the group’s most visible alumnus (thanks in part to his connection to President Obama), and his memoir is a compelling tale of youth in earnest revolution, but some have criticized him for glamorizing the period. Wilkerson’s book offers a kind of counterpoint. Her family’s Greenwich Village townhouse was destroyed in 1970 when a basement cache of pipe bombs accidentally exploded. Wilkerson went underground for a decade before finally turning herself in to authorities and serving a year in prison. Her recollections of the movement are more somber and more critical than Ayers’, especially with regard to the role women were allowed to play. Almost 50 years on, the Weather Underground continues to fascinate, with no shortage of memoirs, histories and critical studies.

Assata: An Autobiography, Assata Shakur

Shakur’s life has been tumultuous beyond imagining: from a childhood in New York and Jim Crow North Carolina to her days with the Black Panthers and her eventual split to become one of the leaders of the Black Liberation Army, a militant offshoot formed in the days of COINTELPRO and infighting. Over the course of the 1970s, Shakur was charged with a number of bank robberies, assaults, and eventually the murder of a state trooper on the New Jersey Turnpike. Her autobiography includes a description of the conditions in which she was kept after the shootout, when she was denied proper treatment and kept chained to a bed beside a dead body. She was convicted (on what many consider dubious evidence) and sentenced to prison, but escaped two years later and fled to Cuba, where she still lives. The US government has labeled her a domestic terrorist and put a multi-million dollar bounty out for her capture. But her autobiography, whatever you think of the BLA’s tactics or Assata’s culpability, tells an eye-opening story.

The Making of a Chicano Militant, Jose Angel Gutierrez

The Chicano movement might not have the same pop cultural caché as other 60s activist causes, but it’s likely to be the force that most dramatically reshapes American society in the 21st century, and Gutierrez was there from the outset. He grew up in the post-WWII borderlands of Texas and witnessed the exploitation and disenfranchisement of the Mexican-American working class. After graduating from Texas A&M and doing a brief military stint, he went back to Cristal and helped found the Mexican American Youth Organization, then later headed up Raza Unida. Gutierrez is an eminent figure now, but his memoir comes alive recalling the early days and the communities that first came together to demand dignity, rights, and a place in American society.

To Dwell in Peace, Daniel Berrigan

Berrigan, who died last year at the age of 95, was a hardened anti-war activist, one of the country’s most wanted men, and a committed Jesuit priest. A member of the Cantonsville Nine (Catholic activists who doused draft cards with napalm), Berrigan went underground in the late 60s and became known as a spiritual guide for many in the radical community. He served time in federal prison but on release resumed civil disobedience. Later in life he turned to anti-nuclear activism and became an advocate for AIDS patients in New York City. To Dwell in Peace, first published in 1987, has become a key text for religious and spiritual radicals, as well as mainstream Catholics unwilling to cede the church to conservative ideologues.

Outlaw Woman, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

In the late 1950s, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, daughter of sharecroppers and IWW men, moved to San Francisco and began her long career in activism. A few years later, in Boston, she founded Cell 16, a militant feminist group, and No More Fun and Games, the journal that would serve as a hub for the rising women’s liberation movement. Dunbar-Ortiz and her group were key members of the New Left, but also served as critics of the imbalanced gender politics that marked many of the era’s radical groups. Outlaw Woman is a thoughtful and meditative story, respectful of the youthful energy that fueled the work, but capable also of quiet moments of startling self-reflection. Now in her late seventies, Dunbar-Ortiz is still active and writing.

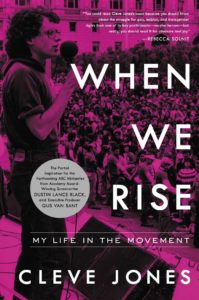

When We Rise, Cleve Jones

In December 2016, Cleve Jones, famed LGBT activist and the man behind the AIDS Memorial Quilt, released a new memoir spanning his life and work. He moved to San Francisco in the 1970s and soon found himself working for Harvey Milk. After Milk’s assassination, Jones and others re-dedicated themselves to the gay liberation movement, only to find it decimated by the start of an epidemic. Jones’ memories are thickly populated and a sense of community prevails throughout his story, from the political battles (and tragedies) of the Milk era to the hospital visits of the 1980s. But he’s also a brawler, unafraid to call out those within the movement who haven’t done enough, not to mention government officials and agencies whose neglect or hostility stood in the way of progress. His life and work are getting a new screen treatment next month (Emile Hirsch played him in the movie Milk), with an ABC miniseries developed by Gus Van Sant and Dustin Lance Black.