10 Slovak Women Writers We'd Love to Read in English

"Slovakia has yet to make a real mark on the English-speaking literary market"

With only ten books of fiction by Slovak authors published in English translation over the last 15 years, Slovakia has yet to make a real mark on the English-speaking literary market. On the bright side, half of these books are by women writers (although the same cannot be said of some dozen anthologies published over the same period, in which women are shamefully underrepresented). Nevertheless, this is just the tip of the iceberg of a vibrant literature, where women writers have gradually become a major force. The authors that we—a group of translators and literature scholars—have selected for this list represent a range of generations and their works reflect experiences past and present, from Slovakia and abroad, some originally written in languages other than Slovak.

We decided to start with a pioneering work from the 1960s by Jaroslava Blažková. Sadly, she passed away at the age of 83 on February 20, 2017, before this list was completed so, in a way, it has turned into a tribute to an author who inspired generations of women writers and whose life epitomizes the upheavals of the 20th century. After she fled to Canada following the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, Blažková was erased from Slovak literature and her books were banned. In a 1997 interview, she said: “Certain stages of life are irretrievable. 1989 came too late for me. When I received a letter from Bratislava asking how I envisaged my rehabilitation, I found it absurd. All I wanted was for my books to be reissued.” ASPEKT publishing house stepped up to the plate, reissuing several of her 1960s books as well as publishing two new ones, written after 2000.

Jaroslava Blažková, Nylonový mesiac (The Nylon Moon)

Slovenský spisovateľ, 1961

Jaroslava Blažková is often called the Slovak Françoise Sagan. Her writings include almost lyrical depictions, similar to Sagan’s, of the fragile and elusive, paradoxical nature of closeness and loneliness, the reluctunce of young women to submit to authority and settle into a mundane and humdrum marriage. Her novel The Nylon Moon tells the story of the exotic blonde Vanda and her brief relationship with the fickle and immature Andrej. It was turned into a feature film in 1968, shortly before the author left the country and before her works were banned.

Why translate it?

A novel of growing up in the 1960s, a time when the 20th century was also growing up and rebelling, The Nylon Moon highlights the absurdity of conservative, petty bourgeois conventions and expectations and is imbued with an intoxicating whiff of freedom, which at the time of publication stirred up controversy similar to that caused by the writing of Françoise Sagan.

–Aňa Ostrihoňová

Irena Brežná, Die beste aller Welten (The Best of All Worlds)

Ebersbach & Simon, 2008

This autobiographical novel depicts Slovakia in the early 1950s through the perspective of a young girl whose family has been persecuted as “class enemies” under Soviet-imposed ideology. Brežná expresses her criticism of the Communist regime with characteristically East Central European irony, referring obliquely to the different languages and cultural backgrounds of the characters, and she reveals the absurdity of the society through her protagonist’s genuinely naïve reactions to events. Although she emigrated to Switzerland in 1968, Brežná has only emerged as a major novelist over the past decade. She writes primarily in German, but has received several awards in Slovakia and was recently the subject of a documentary film.

Why translate it?

Like most of Brežná’s work, The Best of All Worlds was translated into Slovak (under the title Na slepačích krídlach / On Chicken Wings); it has also been published in Czech, French, and Belarusian. An excerpt from the already-completed English translation appeared in the online journal BODY, but it deserves to be published in full, so that a wider readership can experience her distinctive mix of empathy, humor, and barely concealed rage at political injustice in both the former Eastern bloc and the West.

–Charles Sabatos

Jana Bodnárová, Náhrdelník/Obojok (Necklace/Choker)

Trio, 2016

With her latest novel the poet and fiction writer Jana Bodnárová proves that the powerful storyline has not vanished from Slovak literature. The book’s present-day protagonist Sára revisits the time of World War II as she tries to decide what to do with the house in which her family had spent most of their lives. Composed of fragments from the life of a painter, Imrich, the novel depicts not just wartime and the postwar period but also the subtle distinction between the pleasant and choking sensations aroused by a necklace, showing how closely interlinked and interdependent they are.

Why translate it?

Fragments of Sara’s family history and those of her friends, inhabitants of a small town in northern Slovakia, reflect the history, paradoxes and paranoias of the 1950s, the tightening noose of the Cold War and the Iron Curtain, which was every bit as savage as the war they managed to survive.

–Aňa Ostrihoňová

Zuzana Cigánová, Špaky v tŕní (Cigarette Butts in the Brambles)

VSSS, 2012

Pipina is an ugly woman in a world where ugliness is worse than a death sentence. Alone with a baby, she lives amid the thousand cruelties of everyday life and her beautiful, cinematic dreams. She creates a rich inner world, and her razor-sharp observations leavened with a good dose of self-deprecating humor and inventive language produce a revealing narrative of contemporary society.

Why translate it?

You don’t have to be ugly to experience the everyday prejudices of the world around you. Cigánová pulls back the veil on people’s most private thoughts and presents them so matter-of-factly you won’t even notice they could be your own.

–Magdalena Mullek

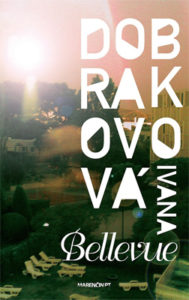

Ivana Dobrakovová, Bellevue

Marenčin PT, 2010

Blanka is a Slovak student who travels to the south of France for a summer job at a home for the disabled. As her initial idealism gives way to irritation and repulsion, and we gradually discover that her sometimes shocking, attitude is not caused by lack of empathy but is a symptom of her mental breakdown. Blanka struggles to hold on to her sanity without medication, turning to her fellow volunteers for help but finds herself as helpless as her former patients and ends up hospitalized. This gripping novel offers an unflinching portrayal of mental illness, still regarded as a taboo.

Why translate it?

Because of the skillful way the author shifts the registers and alternates between the narrative styles reflecting her narrator’s mounting paranoia and increasingly tenuous grip on reality, she is able to create a chilling yet ultimately compassionate portrayal of a frightening condition.

–Julia Sherwood

Irena Eliášová, Naše osada (Our Settlement)

KVK Liberec, 2009

Irena Eliášová is another writer of Slovak origin who does not write in Slovak; her native language is Romany and her works are mainly in Czech (though often with some dialogue in Slovak and Romany). While the episodic narrative is a fictionalized version of the author’s own childhood in a Slovak osada (Roma or “gypsy” settlement) in the early 1960s, it presents an affectionate but unsentimental view of Roma culture. Eliášová’s story reveals a minority deeply connected to its traditions, yet confronted with ideological and technological change under state socialism. However, the heart of the text is provided by the friendship between the endearing narrator Guzka and her best friend, a non-Roma Slovak boy, filtering social problems through the innocent perspective of childhood in a way similar to classics such as To Kill a Mockingbird.

Why translate it?

The Roma minority of former Czechoslovakia remains culturally marginalized, and there are very few literary depictions of contemporary Roma life, even fewer by authors of Roma origin themselves. Eliášová is little-known in the Czech Republic, where her books have been printed by obscure publishers in small print runs, and she is almost unknown in Slovakia. However, her vivid characterizations, her lively story-telling, and her unique insights into the vanishing traditions of Slovak Roma culture make her work a worthy candidate for translation into English and other European languages.

–Charles Sabatos

Zuska Kepplová, Buchty švabachom (Rolls in Blackletter)

KK Bagala, 2011

Petra, Anka, Mika, Natália, Juliana—Paris, London, Helsinki, Budapest—a series of stories about present-day nomads, young people who go out into the world in search of a better life, or maybe just a different one. While they have the freedom to study anywhere in the world and work in countries their parents could not even visit, the reality of that “freedom” is often nothing more than menial work, poor living conditions, and Tesco value products. Kepplová’s light touch makes this an easy read if you’re willing to discard all expectations and allow yourself to be carried along on their journeys towards their own ideas of freedom.

Why translate it?

A millennials’ odyssey—a search for self by the post-Cold-War generation, which has lived its entire life in the rapidly changing global economy—this book has been called a pocket Baedeker for the world of young Slovaks, but they could equally be Polish, Slovene, or any other Central European nationality.

–Magdalena Mullek

Monika Kompaníková, Piata loď (Boat Number Five)

KK Bagala, 2012

This short novel follows a young girl desperately and sometimes humorously fashioning a life for herself. Emotionally neglected by her immature, promiscuous mother and made to care for her witch-like, dying grandmother, 12-year-old Eva is left to fend for herself in the social vacuum of a post-communist concrete apartment block jungle in Bratislava. She spends her days roaming the streets and daydreaming in the only place where she feels safe—a small garden inherited from her grandfather. One day, on her way to the garden, she stops at a suburban railway station and impulsively abducts twin babies. Eva teeters on the edge of disaster, struggling to care for them, while discovering herself.

Why publish it?*

With a vivid and unapologetic eye Kompaníková captures the emptiness and ache of the post-communist environment. Even in a society where city neighborhoods were built as communities, socialist ideology not only “equalized” people, but also equally humiliated them. This book is about the aftermath of that experience and one girl’s quest for genuine human relationships.

–Janet Livingstone

* An extract of Boat Number Five appeared in Words without Borders and the complete book is available in Janet Livingstone’s English translation. Little Harbour, a film based on the novel, won a Crystal Bear at the 2017 Berlin Film Festival.

Vanda Rozenbergová, Slobodu bažantom (Freedom for Pheasants)

Slovart, 2015

The central theme of the 15 short stories in this collection is freedom. However, this is not freedom understood as a theatrical gesture, as Rozenbergová’s protagonists opt for an unflashy, maybe even eccentric, kind of revolt. Ordinary at first sight, these are unconventional adventurers rebelling against mortifying, preordained existence. Their compassion or solidarity with those who are weaker turns them into quiet avengers who take on animal abusers, domestic tyrants and cruel partners, helping their victims to find the strength to live a free and contented life.

Why translate it?

The stories’ plots are filled with small miracles and playful imaginings, all the while remaining plausible and convincing. Rozenbergová has the courage to let her characters engage with the world passionately, to embrace it and be a force for good. Even when they fail, her protagonists keep trying to win the affection of others and never lose hope of achieving something more. Freedom for Pheasants shows that Rozenbergová is one of the most original and promising figures on the contemporary Slovak literary scene.

–Ivana Taranenková

Veronika Šikulová, Miesta v sieti (Places in the Net)

Slovart, 2011

This strongly autobiographical novel is set mainly in Bernolákovo, a small country town in the south of present-day Slovakia (and home to Slovaks, Hungarians and Germans, known at various times as Cseklész, Čeklís and Landschütz) that has been claimed, in turn, by Hungary and Czechoslovakia. The three protagonists—grandmother Jolana, mother Alica and daughter Verona (Šikulová herself)—speak in turn, their monologues gradually revealing their family history and through it the 20th-century history of Central Europe. Places in the Net is a novel of reminiscences and memories, of personal and national tragedies, of joys, colors and scents, but above all a novel of three strong women, who somehow manage to find the courage and strength to keep going—regardless of what history and fate throw at them.

Why translate it? Šikulová’s writing smartly recreates her protagonists’ world, alternating their distinct voices, reflecting the characters’ social standing, education and personality. In addition to the wealth of historical and factual detail, the bilingual setting that permeates the monologues and the narration presents a formidable challenge to a translator. However, having translated the book into Hungarian I can affirm that this is a challenge a resourceful English translator would ultimately find rewarding, as the book provides original insights into this unique borderland area, as well as a chance to see it through Šikulová’s very personal, and feral yet tender, unequivocally feminine filter.

–Tünde Mészáros

Julia Sherwood

Julia Sherwood was born and grew up in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia (now the Slovak Republic). Since 2008, she has been working as a freelance translator from Slovak, Czech, Polish, Russian and German into English (with Peter Sherwood), as well as into Slovak. In addition to book-length publications, her work has appeared in Two Lines, BODY.Literature, The Missing Slate, Words Without Borders, OpenDemocracy, Eurozine, Aspen Review and salon.eu.sk. She is editor-at-large for Slovakia for Asymptote, the international online literary journal, and administers the group Slovak Literature in English Translation.