10 Little-Known Children’s Books by Famous Writers

Featuring at Least Two of the Best Titles Ever Written

This week, Duke University Press is reissuing James Baldwin’s children’s book, Little Man, Little Man. If you had no idea that James Baldwin ever wrote a children’s book, you’re not alone. In fact, quite a number of established literary writers have dabbled in kids lit. Most people know about the children’s books of writers like Ian Fleming (Chitty Chitty Bang Bang), Salman Rushdie (Haroun and the Sea of Stories), T.S. Eliot (Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats), Toni Morrison (The Book of Mean People, etc) and even Mark Twain (Advice to Little Girls). But others are more obscure, and in honor of the republication of James Baldwin’s only children’s book, here are a few of these, all of them children’s books (even if made into them after the fact) and all written by writers more famous for their grown-up fiction. Lots more can be found, by the way, at novelist Ariel S. Winter’s lovely but currently dormant blog We Too Were Children, Mr. Barrie. Check it out.

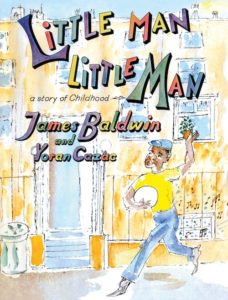

James Baldwin, Little Man, Little Man (1976)

James Baldwin, Little Man, Little Man (1976)

Newly available from Duke University Press is James Baldwin’s only children’s book, which as Alexandra Alter reports in the Times, “unfolds from the perspective of a curious, irrepressible 4-year-old boy named TJ, who loves music and playing ball, and navigates a neighborhood where gun violence, police brutality, alcoholism and drug addiction are looming threats—an outside world that even his warm home life with loving parents can’t shield him from.” The book was partially inspired by Baldwin’s nephew, Tejan Karefa-Smart, who used to pester his uncle to write about him.

“I must tell you, I was very frightened to try to write a children’s story or a story for children, because first of all, I think children object to being called children,” Baldwin told a group of children in 1979. “The one thing a child cannot bear is to be talked down to, to be patronized, to be talked to in baby talk. So what I tried to do was put myself inside the minds of the kids in my story, trying to remember what I myself was like when I was a kid, and the way I sounded, and the way TJ sounds.”

The watercolor images were created by Yoran Cazac, whom Baldwin met while living in the south of France, but who had never been to America. They are lovely and kinetic and very much worth a look—plus, you know, James Baldwin!

*

bell hooks, Happy to Be Nappy (1999)

bell hooks, Happy to Be Nappy (1999)

You may know her as a legendary author, feminist thinker, and social activist, but bell hooks also wrote a number of board books (yes, board books, the cutest kind of books!) for small children. These include the above Happy to be Nappy, and also Homemade Love, Grump Groan Growl, and others. Unsurprisingly, this one is an adorable ode to girls and their hair:

Happy to be nappy!

Happy with hair all short and strong.

Happy with locks that twist and curl.

Just all girl happy!

Happy to be nappy hair!

*

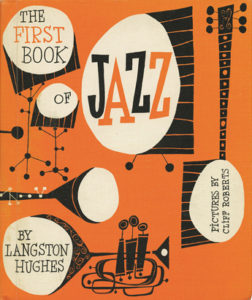

Langston Hughes, The First Book of Jazz (1955)

Langston Hughes, The First Book of Jazz (1955)

In 1955, Langston Hughes, arguably the most important poet of the Harlem Renaissance, published a jazz explainer book for children! It was the first children’s book to tackle the subject, and it’s a good one: a history of the art form—in sections with titles like “African Drums,” “Old New Orleans,” “Work Songs,” “Jubilees,” “The Blues,” “Ragtime,” and “Boogie-woogie”—and an explanation of the terms, from syncopation to riff. “A part of American music is jazz, born in the South,” Hughes writes. “Woven into it in the Deep South were the rhythms of African drums that today make jazz music different from any other music in the world. Nobody else ever made jazz before we did. Jazz is American music.” NB that The First Book of Jazz was actually the third children’s book written by Hughes. The first was The First Book of Negroes and the second was The First Book of Rhythms. You see the theme here.

*

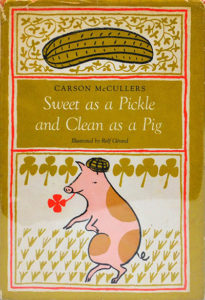

Carson McCullers, Sweet as a Pickle and Clean as a Pig (1964)

Carson McCullers, Sweet as a Pickle and Clean as a Pig (1964)

You can’t beat the title—or cover, for that matter—of Carson McCullers’s collection of poems for children. Unfortunately, the rest of it doesn’t seem to be as successful. “The book was not well received, and it’s not hard to see why,” Ariel S. Winter wrote. “The poems alternate between light nonsense verse in the vein of Mother Goose, and free verse observations and reminiscences tinged with melancholy. It’s hard to imagine what child would be drawn to such disparate work, especially since the poems are neither funny nor particularly rhythmic.” One poem, entitled “Song for a Sailor,” goes like this:

I’ve never seen the ocean,

I’ve never seen the sea,

But once I loved a sailor,

And that’s good enough for me.

Well, it’s almost right . . .

*

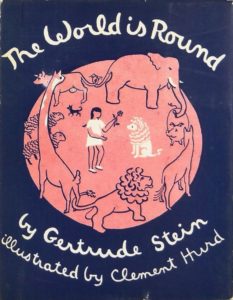

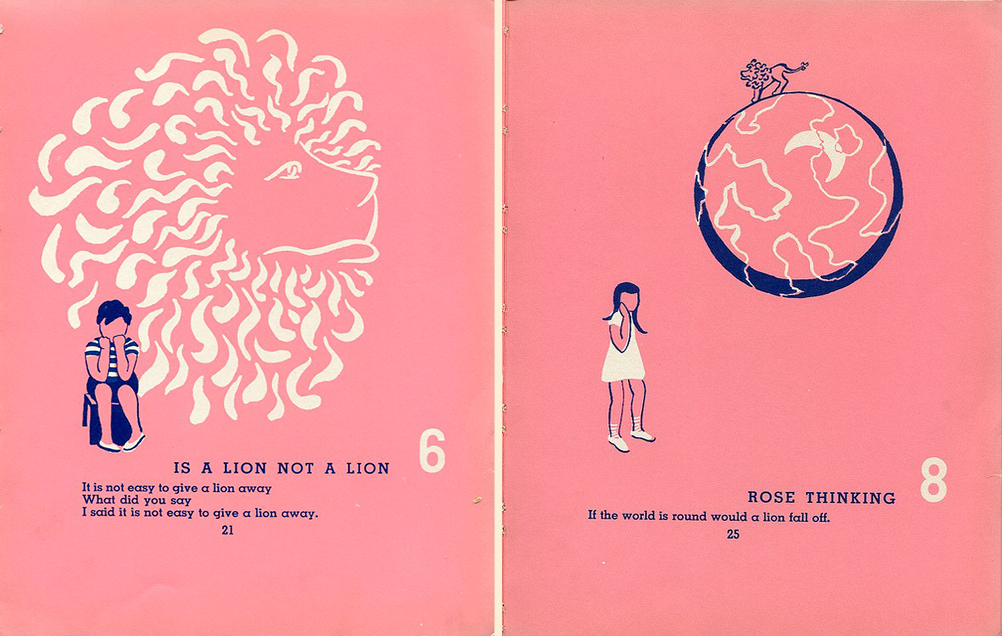

Gertrude Stein, The World is Round (1938)

Gertrude Stein, The World is Round (1938)

This book is exactly the children’s book I would expect Gertrude Stein to write: obscure and poignant and strange and delightful. It was published by Young Scott Books, after one of their new authors, Margaret Wise Brown (maybe you’ve heard of her), reached out to Stein, as well as Ernest Hemingway and John Steinbeck, asking them to write children’s books. The men declined, but Stein already had a manuscript and happily submitted it. After some struggle (over, you’ll be shocked to hear, whether it was accessible enough), it was accepted. However, according to Maria Popova, Stein had some demands. The pages had to be pink. The ink had to be blue. The illustrator had to be Francis Rose. She got two out of the three—the drawings, in the end, were created by Young Scott standby Clement Hurd, who also illustrated Goodnight Moon and The Runaway Bunny.

Here’s how the book begins:

Once upon a time the world was round and you could go on it around and around.

Everywhere there was somewhere and everywhere there were men women children dogs cows wild pigs little rabbits cats lizards and animals. That is the way it was. And everybody dogs cats sheep rabbits and lizards and children all wanted to tell everybody all about it and they wanted to tell all about themselves.

And then there was Rose.

Rose was her name and would she have been rose if her name had not been Rose. She used to think and then she used to think again.

Read more here.

*

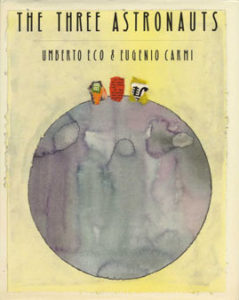

Umberto Eco, The Three Astronauts (1966)

Umberto Eco, The Three Astronauts (1966)

All told, Eco and Eugenio Carmi published three children’s books together; this is the second one, the middle child. In it, three astronauts from three different countries (the US, Russia, and China) send men to Mars. Topics covered include: Space exploration! World peace! Aliens! Tolerance! Everyone loving their moms! Great.

*

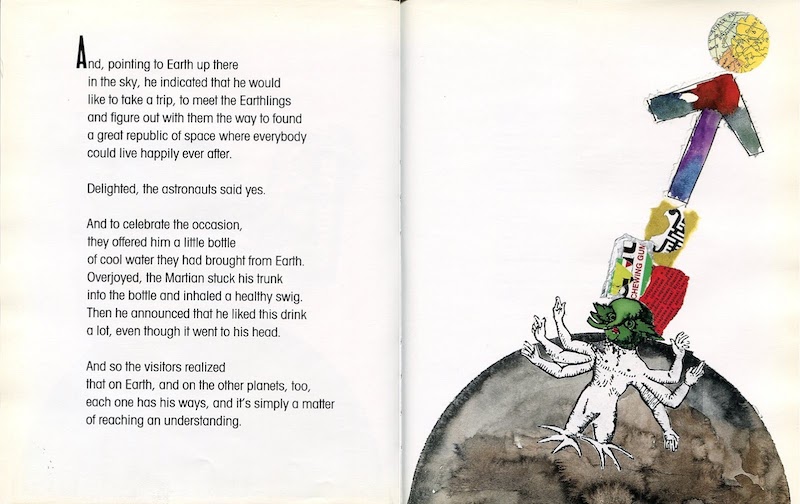

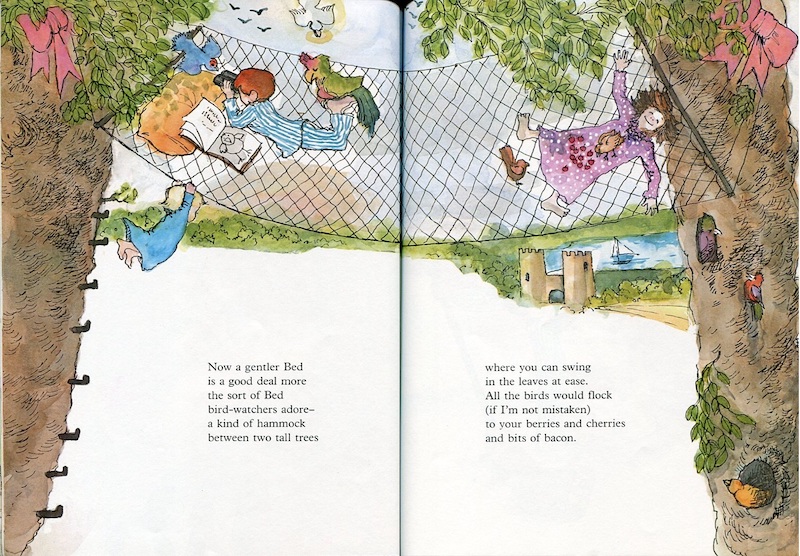

Sylvia Plath, The Bed Book (1976)

Sylvia Plath, The Bed Book (1976)

Here in the literary world, we love Sylvia Plath. We think about her all the time. We obsess over her doomed marriage. We argue over what she should wear on book covers. We purchase her personal effects. We constantly re-evaluate her life and personality. But, focused as we are on her tragedy, her heartbreak, her suicide, and, to be fair, her extremely good poems, we very rarely talk about the fact that she also wrote two children’s books: The It-Doesn’t-Matter-Suit (1966) and The Bed Book (published posthumously in 1976), as well as another story, “Mrs. Cherry’s Kitchen,” later collected with the first two. Though it was published second, The Bed Book was written first. As Ariel S. Winter points out in a blog post about the book, Plath wrote about its conception in her journal on May 3, 1959:

I wrote a book yesterday. Maybe I’ll write a postscript on top of this in the next month and say I’ve sold it. Yes, after half a year of procrastinating, bad feeling and paralysis, I got to it yesterday morning, having lines in my head here and there, and Wide-Awake Will and Stay-Uppity Sue very real, and bang. I chose ten beds out of the long list of too fancy and ingenious and abstract a list of beds, and once I’d begun I was away and didn’t stop till I typed out and mailed it (8 double-spaced pages only!) to the Atlantic Press. The Bed Book, by Sylvia Plath. Funny how doing it freed me. It was a bat, a bad-conscience bat brooding in my head . . . A ready-made good idea and an editor writing to say she couldn’t get the idea of it out of her head.

That editor was Emilie McLeod, of the Atlantic Monthly Press, who loved the book, but ultimately couldn’t get it past the publisher. It wouldn’t be published until 1976, both in the US, with illustrations by Emily Arnold McCully, and in the UK, with illustrations by Quentin Blake.

*

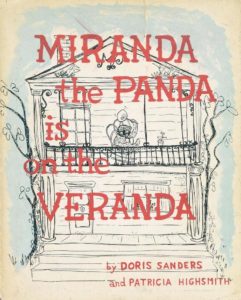

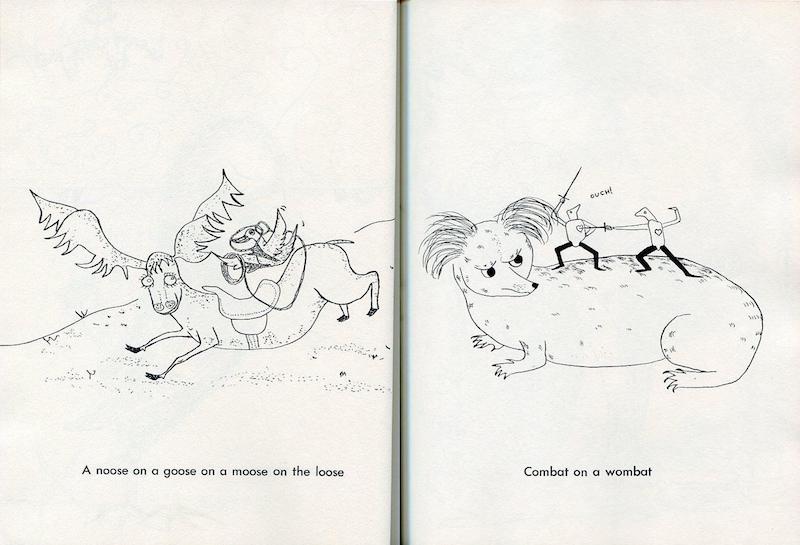

Patricia Highsmith, Miranda the Panda is on the Veranda (1958)

Patricia Highsmith, Miranda the Panda is on the Veranda (1958)

Here’s another really good title from an author I had no idea published any children’s books. In fact she produced only one, in 1958, with Doris Sanders, a copywriter with whom she was romantically involved. In a shocking twist (for this list at least) it was actually Sanders who wrote the copy—a series of short nonsense rhymes like one used for the title—and Highsmith who drew the illustrations.

*

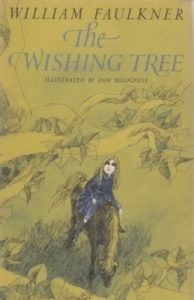

William Faulkner, The Wishing Tree (1927)

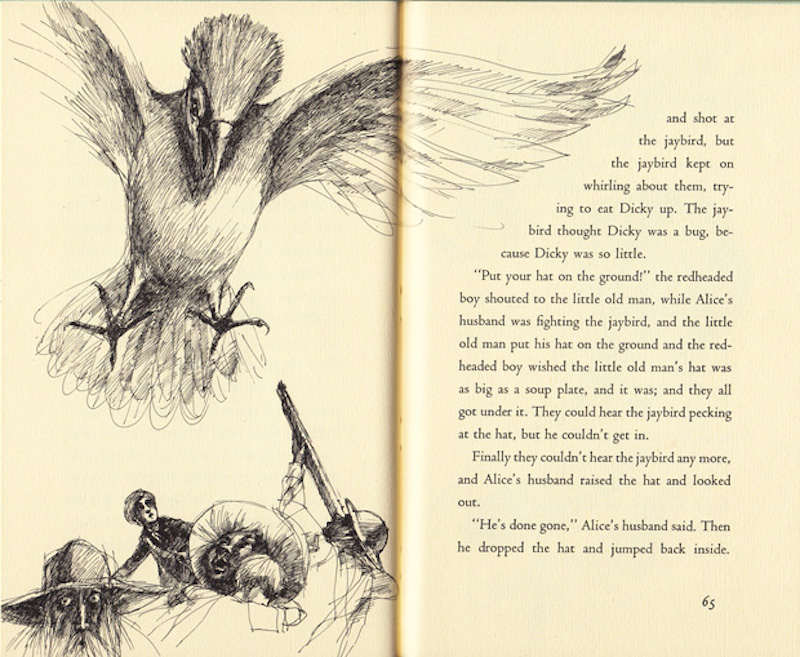

William Faulkner, The Wishing Tree (1927)

William Faulkner only wrote one children’s book—which Maria Popova calls “a sort of grimly whimsical morality tale, somewhere between Alice In Wonderland, Don Quixote, and To Kill a Mockingbird, about a girl who embarks upon a strange adventure on her birthday only to realize the importance of choosing one’s wishes with consideration and kindness”—and it was really only meant for one child: Victoria Franklin, the daughter of his childhood sweetheart Estelle Oldham. Estelle was still married to Victoria’s father, but Faulkner hoped she would cast him off and remarry him instead, which she did two years later—maybe in part because of this book, which Faulkner illustrated and lovingly bound himself. On the first page, he wrote:

For his dear friend

Victoria

on her eighth birthday

Bill he made

this Book

Anyone would marry such a gentleman! That said, as Popova points out, Faulkner made copies of the book for at least three more children. Not a problem until Victoria Franklin tried to publish hers—which she eventually did, with Random House, in 1964.

*

*

James Joyce, The Cat and the Devil (1964)

James Joyce, The Cat and the Devil (1964)

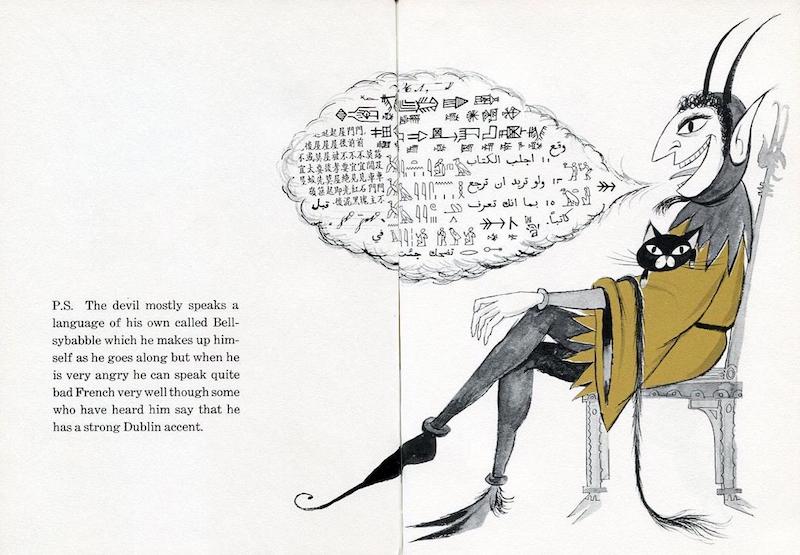

The Cat and the Devil began as a letter to Joyce’s grandson, Stephen Joyce. “I sent you a little cat filled with sweets a few days ago,” he wrote, “but perhaps you do not know the story about the cat of Beaugency.” He goes on to tell him about the time the Devil built a bridge across the Loire for the people of Beaugency, with the condition that the first soul to cross the bridge would belong to him forever—and how the Mayor tricked a cat into being the soul in question. The story was originally published in 1957 in a collection of Joyce’s letters, and was later titled and published as a children’s book in 1964, with illustrations by Richard Erdoes. Two more editions followed: one illustrated by Gerald Rose in 1965, and another illustrated by Roger Blachon in 1980. The James Joyce Centre points out that:

The Devil in the story sounds like Joyce himself, always reading newspapers, speaking his own language “Bellsybabble,” and also speaking bad French with a Dublin accent when he’s angry. As the Mayor, Joyce cast the actual Lord Mayor of Dublin at the time, Alfred Byrne (1882-1956). Byrne was Lord Mayor an astonishing nine times in a row from 1930 to 1939, and Joyce claimed that every time he opened the Irish Times there was a photograph of Alfie Byrne, adorned with his gold mayoral chain, in it.

It is a delight.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.