Separating Truth from Lies in the Face of Atrocity

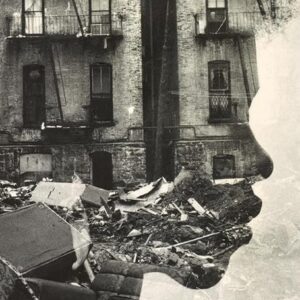

What, after all, is a truly verifiable or “authentic” image?

This essay appears in issue 99 of Brick.

On the night of October 21, 1967, my father, Lance Corporal Olaf Skibsrud, 21 years old and serving as a marine in Vietnam, witnessed the murder of a civilian woman at the hands of one of his superiors. Deeply troubled by the incident, he reported it to the company chaplain and an Article 32 investigation ensued, in which my father and a number of other witnesses were called to testify. The transcript of my father’s testimony, excerpted from the 500-page document produced during the investigation into the still-controversial events surrounding what became known as “the incident at Quảng Tri,” was forwarded to me in 2006 by my father, who had received it from historian Gary Kulik, then at work on his own account of the event.

A decorated veteran of the Vietnam War, Kulik had served as a medic in the same company as my father and had heard rumours of the Quảng Tri affair at the time it occurred. Later, he became aware of the version of events recorded by former marine Terry Whitmore in his 1971 memoir, Memphis-Nam-Sweden: The Story of a Black Deserter, in which Whitmore claimed that more than 300 civilians had died as a result of Operation Liberty II at Quảng Tri. Though Kulik had not been in the field at the time, Whitmore’s version of the incident seemed blatantly fabricated—one of many “false atrocity tales” that were becoming more and more common during and following the Vietnam War. These were stories that exaggerated—or even seemed to brag about—the horrors of veterans’ experiences, as if in answer to the civilian perception of an increasingly unpopular war.

Kulik concludes his book by saying:

The reason to expose false atrocity stories is so we can retain our outrage at true atrocity stories. Otherwise it’s all noise, feeding into the widespread belief that atrocities defined American conduct in Vietnam. The credulous belief in such stories dishonors the service of those soldiers who acted with honor, who did not kill Vietnamese villagers, and who were not party to covering up the killing of children.

But even as Kulik was attempting to lay to rest the false atrocity stories that emerged during and in the wake of the American conflict in Vietnam, a new generation of stories was emerging with an even murkier relationship to “truth” and “falsity,” categories Kulik was endeavoring to reinforce. Where atrocity tales from the Vietnam War and earlier wars could easily be deemed incredible due to a lack of documentation, in an era of social media, “fake news,” and a steady onslaught of information and images representing every imaginable “point of view,” it is documentation itself that has become incredible.

Journalists have long acknowledged the uncertain relationship between the presentation of “facts” and the facts themselves and, always wary of the possibility of their own implicit bias, have avoided drawing a hard line between “truth” and “falsity” in the stories they report. But with a sharp increase in “fake history” and “fake news” leading up to and following the 2016 U.S. general election, many journalists have begun to rethink their relationship to these categories and—as Charles Taylor puts it in a recent article published in the Boston Globe—to call “a lie a lie.”

However, on New Year’s Day 2017, Wall Street Journal editor-in-chief Gerard Baker warned against getting too comfortable with the word. “Lie implies much more than just saying something that’s false,” he said. “It implies a deliberate intent to mislead.” The term, he later wrote, “conveys a moral as well as factual judgment.” Instead of making such judgments, journalists should be presenting their readers “with the facts.”

The desire to sort “fact” from “fiction” and “truth” from “lies” may feel especially urgent today. But in an age of “fake news,” with a surplus of documentation and a collective history so heavily mediated that even while it is happening it often feels “fake,” how can we begin to reclaim these distinctions? It is not for nothing that we have developed an appreciation of the dangerous and essentializing nature of truth claims—or their summary dismissal—or that we have learned to recognize the inherent partiality of every form of representation and the ways in which even a seemingly “objective” medium like photography relies heavily upon, and sometimes exploits, the imagination. A critical approach to media in all of its forms and a resistance to believing something when we read, hear, or see it is prudent, even necessary today—and yet such circumspection can also obscure the very real issues that every form of media (just like every human being) subjectively and partially conveys.

When Kulik dismissed Whitmore’s account of Operation Liberty II as categorically false due to its subjective and undocumented nature, he did so by dismissing the complicated relationship atrocity tales have always had with the categories of truth and falsity—including the question of why, if the story was false, Whitmore chose to account for his experience that way. When atrocity tales are obscured or dismissed today due not to a dearth but instead to an excess of documentation, we risk swinging heavily in the opposite direction and dismissing the complicated relationship that subjective, always partial documentation has to the facts.

The case of the Abu Ghraib “hooded man” photograph from 2003 is one example of this contemporary tendency to focus on the inherent unreliability of subjective experience and its documentation while overlooking the broader reality of which this unreliability is a part. The photograph was circulated widely, causing a brief uproar among a public who was already ambivalent about U.S. involvement in Iraq and the “enhanced interrogation techniques” that were—now very apparently—being employed.

Then, in 2006, the New York Times published an article on the “hooded man” that featured an image of a former detainee at Abu Ghraib, Ali Shalal Qaissi, holding the infamous photograph. It soon came out that although Qaissi had also suffered abuse at Abu Ghraib he was not the man in the photograph. The article was quickly retracted, and very soon the established fact that Qaissi was not the iconic “hooded man”—that the published article was inaccurate on this point and that Qaissi had lied—began to eclipse what both Qaissi and the “hooded man” photograph clearly attested to: there were people being tortured at Abu Ghraib.

In his own New York Times article, published in 2007, “Will the Real Hooded Man Please Stand Up,” Errol Morris investigated the “central role that photography itself played in the mistaken identification, and the way that photography lends itself to those errors and may even engender them.” It may be, Morris suggested, that an emphasis on documentation over a more comprehensive and intimate (and thereby more complex) approach to the people we encounter, the issues we explore, and the stories we tell can lead us toward a veracity that has very little to do, in the end, with truth.

In 2006, my father was just as skeptical about Kulik’s project as Kulik was about Whitmore’s. “He wants the ‘facts,’” he told me after Kulik first contacted him by telephone. The irony in his voice was thick. Still, after some initial resistance, my father complied with Kulik’s request. He reported his own story dutifully, in the same spirit as he had in the initial investigation: “Well, sir, I’ve only answered the questions that have been asked to the best of my ability.”

Forty years later, my father’s account of the incident was more or less consistent not only with his original testimony of November 22, 1967, but also with the official U.S. record of civilian deaths; because of this, his story soon became the central axis upon which Kulik’s historical account of the operation turned. That this should be so is at the very least worthy of some reflection. Even one month after the incident in question, my father’s description of the events and confidence in his own reliability were tentative at best. He said then—and afterwards it was even more clear to him—that he had witnessed the incident in a state of emotional shock. No doubt based on what he saw as the provisional quality of his own memory and experience, he had wondered openly if the “facts” in this case had ever existed at all.

Errol Morris writes of the “hooded man” photograph: “Believing is seeing, not the other way around.” What we “see” is determined not by any accessible objective reality but by our most deeply held predispositions and expectations. An insistence on establishing the “authenticity” of the images and narratives presented to us often obscures the real issues: our deeply ingrained prejudices, ideals, and beliefs. “Facts,” according to Morris, are very much like photographs in that they allow us to think we know more than we really do. We can imagine a context that isn’t really there. . . . With the advent of photography, images were torn free from the world, snatched from the fabric of reality, and enshrined as separate entities. They became more like dreams. It is no wonder that we really don’t know how to deal with them.

A U.S. Marines spokesperson, Captain Kendra Hardesty, articulated the tentative and troubled relationship media images have with reality when, following the release of a video in January 2012 that depicted four U.S. Marines urinating on a dead man, she said, “While we have not yet verified the origin or authenticity of this video, the actions portrayed are not consistent with our core values and are not indicative of the character of the marines in our corps.”

By emphasizing the possible unreliability of the documents, Hardesty managed to direct the conversation past the (present, apparent) documented reality toward an (absent) rhetorical one. Rather than believe what we see, in other words, Hardesty asks us to put our faith in what we would like to see, what we would like to believe. She destabilizes the image by directing our attention to its essential and irremediable separation from the reality it represents. What, after all, is a truly verifiable or “authentic” image?

Errol Morris explores this question by comparing two available versions of Roger Fenton’s “Valley of the Shadow of Death” photograph taken in 1855 during the Crimean War: one depicting a stretch of road littered with cannonballs and the other depicting the same road cleared. Which photograph is original and authentic, Morris asks, and which one is posed? On second thought, “couldn’t you argue that every photograph is posed because every photograph excludes something?”

What we fail to see when we confront the 2012 urination video—or the hooded man photograph, or the smiling Sabrina Harman photographs, or the transcripts depicting the horrors of the Haditha massacre—is that what we see really is what we see. That these images—even if difficult, partial, “unofficial,” or limited in scope and point of view—reflect the reality in which we live: a reality that fundamentally includes ongoing problems of judgment and interpretation.

“And so,” Kulik concludes his War Stories, “a Vietnamese woman died that morning—shot in the back in front of her children. Mourn for her. She did not deserve to die in that way.” The confidence and definitiveness with which this conclusion is drawn—and with which Whitmore’s account of more than three hundred civilians having died that night is summarily dismissed—is based on the aligning testimonies of two men: Private First Class Ronald P. Toon and my father. “Whitmore lied,” Kulik resolutely declares.

He didn’t exaggerate. He lied. An exaggeration is when you claim that fifty Vietnamese were killed, when ten were, or twenty. He claimed that an entire village was wiped out—300 or so Vietnamese. He offered graphic depictions of those killings—killings that never happened.

It is worth noting that in his attempt to lay to rest one of many false atrocity tales from the Vietnam War era, Kulik relies on the testimony of a man who once suggested to me that if I truly wanted to understand the Vietnam War, I’d be “better off watching the movies. Brando in Apocalypse Now, for instance.”

In suggesting that I might learn more from what is, perhaps, the paramount false atrocity tale of the Vietnam War than I ever could from him, my father never intended that the film reflected his, or indeed anyone’s, direct personal experience, as I first fleetingly supposed. (I remember I laughed out loud, thinking he was joking.) He was suggesting instead that a quality of that experience—a profound sense of confusion and of horror; a sense, indeed, of the unreality of the experience—was, through the film, accurately conveyed. What had been evidently important to my father was not the “facts” that he had spent such a long time trying to forget but the sense of horror, pain, guilt, and confusion that he never would. Implicit also in his suggestion is the idea that our realities are always and necessarily constructed to a certain extent by “unreality”—by what we can hardly perceive, let alone express or understand.

And yet, if we become too comfortable with this idea, as perhaps we already have, we risk losing our collective capacity for outrage not only at false atrocity stories but at any “deliberate intent to mislead.” As Kulik has claimed regarding Whitmore’s account of Operation Liberty II, “the credulous belief” in false stories dishonours those who behave honourably and continue to believe in the difference between fact and fiction, truth and lies. But the problem of why such a vast number of false atrocity tales arose beginning with, and following, the Vietnam War is only partially solved by asking the questions “Which ones are true?” and “Which ones are false?” We need also to be asking, “What is it about these contemporary wars that encourage this form of storytelling?” and “Why do the soldiers who fight them want so badly to identify not as heroes but as victims?” Similarly, if we want to reclaim the difference between “truth” and “lies” in contemporary politics and journalism, we need to be considering not only the question of how we might begin to call “a lie a lie” but also the question of how, and why, we have arrived at a point where so many of us are willing to believe stories that are, as Baker puts it, “as far as the available evidence tells us, untruthful.”

Not only does the true-false distinction fail to address the complexities of our current media climate and therefore of contemporary atrocity tales, so often characterized by the vagaries and limitations of documentation itself, but it also fails to tell us anything about what lies behind the perpetuation of atrocity or the horror of that experience as it is variously expressed.

I first began corresponding with Kulik while writing my first novel, The Sentimentalists, a work of fiction that includes excerpts of my father’s real-life testimony and explores the uncertainty that arises whenever two very different approaches to “truth” and the historical record collide. I had received Kulik’s contact information from my father, and in 2009—one year after my father’s death and shortly before the publication of my novel—I decided to get in touch in order to discuss my father’s transcript.

At the time, Kulik was still at work on War Stories, and after a pleasant email exchange, he requested that I take a look at the profile he had written of my father, correcting any factual errors if I found any. There were a few, and I complied with his request. In return, I asked Kulik if he would be willing to read the Vietnam sections of my novel, again correcting any errors. My father had made me well aware of Kulik’s approach to Operation Liberty II, so I was careful to emphasize that my own project was literary rather than historical, that my motivation was not to reveal the facts but to explore the manner in which they intersected with fiction. Kulik agreed to read the excerpts in question, but after I provided them, our once cordial correspondence stopped abruptly. Kulik asked me not to contact him again, and not to ask why.

I can only imagine, now, that our particular senses of how and for what purpose historical events should be explored and treated were finally too dissimilar. And though I did not believe—though I certainly did not want to believe—that my project contributed to mere “noise” on the subject of Operation Liberty II, “the incident at Quảng Tri,” or the war in general, I was sufficiently bothered by Kulik’s response that a part of me feared this was the case. Where Kulik was interested in “facts,” I was interested in what I could best describe as the spaces between those facts—and that is a far less comfortable place to stand.

A year later, however, reading Kulik’s War Stories, a very different sort of understanding of the phrase “it’s all noise” occurred to me. I suddenly thought, That’s it. Noise. That’s exactly the material out of which our realities are constituted. It was for this reason that my father had cited Apocalypse Now as the most accurate record he could think of to express his experience, though in point of fact nothing about that movie resembled his experience at all.

What literature, history, politics, and, most essentially, language attempt—what is, in short, at the root of every human pursuit—is this same shared effort: to create form from chaos, meaning (and even sometimes music) from noise. We need to attend to—and believe in—the distinction between chaos and form, noise and meaning, but we also need to remember that no distinction is ever final or escapes the contingency of noise.

It is only when we are able to accept this fundamental connection between noise and meaning that we have any hope of moving past an impotent outrage at false stories toward a more far-sighted and thorough interrogation of what’s beneath, and beyond, those stories. It is only when we are able to accept that lies are also, and inevitably, a part of the truths we either accept or refuse that we have any hope of approaching the true horror of the conflicts that continue to be an integral part of our reality—whether we “see” them or not.

Johanna Skibsrud

Johanna Skibsrud is a novelist, poet and Assistant Professor of English at the University of Arizona. Her debut novel, The Sentimentalists, was awarded the 2010 Scotiabank Giller Prize, making her the youngest writer to win Canada’s most prestigious literary prize. The book was subsequently shortlisted for the Commonwealth Book Award and is currently translated into five languages. The New York Times Book Review describes her most recent novel, Quartet for the End of Time (2014) as a “haunting” exploration of “the complexity of human relationships and the myriad ways in which identity can be malleable.” Johanna is also the author of two collections of short fiction: This Will Be Difficult to Explain (2011; shortlisted for the Danuta Gleed Award) and Tiger, Tiger (2018), a children’s book, and three books of poetry. Her latest poetry collection, The Description of the World (2016), was the recipient of the 2017 Canadian Author’s Association for Poetry and the 2017 Fred Cogswell Award. Johanna’s poems and stories have been published in Zoetrope, Ecotone, and Glimmertrain, among numerous other journals. Her scholarly essays have appeared in, among other places, The Luminary, Excursions, Mosaic, TIES, and the Brock Review.