Writing Through the Silences of a Lost Family History

Jonathan Lichtenstein on Unearthing the WWII Past of His Father

I was a child. I was in Wales. I was in the clothes shop in Llanrindod. The shop-bell rang with a tinkle. A man entered—a farmer. He spoke to Johnny Jones, the shop’s owner. The farmer, dressed in Wellington-boots, plaid cap and an olive-green, waxed-cotton jacket seemed to answer a question I hadn’t heard. In a soft Welsh accent he said:

France. Me.

Were you?

Normandy.

I was too

Came to a farm. Kept pigs.

That right?

One of ours killed one of their boys. Wounded two.…..

Afterwards we lifted all three….. into the pigs’ pen.

Really? You did?

Pigs eat everything.

I know

Everyone knows.

The farmer paused and then started to shake, slowly at first, then more rapidly. He stepped forwards and leant upon the glass-fronted shop counter that acted as a showcase for striped ties, braces and dark leather belts. His body rippled like an eel. He made no sound at all.

Johnny, who was small and barrel-chested, and known to be exceptionally strong, stood, braced himself, lifted his knee, snapped his foot downwards and stood to attention. He saluted the convulsing farmer. A silence descended. The farmer shuddered for some time. Johnny remained motionless; his eyes unblinking. When the farmer calmed and stopped shaking he stood up straight. For a second or two the two men faced each other. The farmer saluted Johnny, turned and left the shop. Its bell tinkled as he left. I watched him through the shop’s large plate glass window as he crossed the street. I ruminated on the phrase, “pigs eat everything,” for months.

We stood together in the spot where he said goodbye to his mother.

As a child growing up in the 1960s, I was taught by teachers who had fought, by neighbors who had fought, by uncles who had fought. I was raised by a father who had escaped and by a mother who had been evacuated. In short, I was raised, like many of my generation, by a group of remarkable people—my parents and their contemporaries—who had fought in one way or another during WWII, but at great personal cost.

The trouble was, no one would talk about this personal cost. No one really knew what it was because no one could articulate it. It had no language. Instead there were victory parades and memorials and haunting marches and the Last Post. There was the British Legion and men and women on Armistice Day wearing suits decorated with medals—their military torsos, stiff and unyielding—iridescent pride and gleaming sorrow emanating from their faces as they marched in step past the town’s War Memorial.

The words that described their terrors, their quaking nightmares were not there for them. They weren’t anywhere. It was as though the idea of “victory” had stripped them of the words to illuminate their innermost secrets, their losses, griefs and difficulties, their violences and cruelties. Their madnesses. Their murderous guilts.

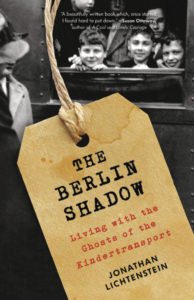

Now it is widely understood by psychologists that trauma endured by one generation comes rushing through to the next. In my book The Berlin Shadow I trace this transmission—how the trauma my father endured came to destabilize not just him but, to my great shame, as I had not suffered at all, mine too. Over many years I came to understand that I had been infused part of my father’s traumatic history. Why this happened I do not know. All I do know is that it became the dark ghost inside me, the lining of my heart, the stones of my kidneys. His unspoken pain surrounded me, then settled inside me—and despite my battles with it, it gripped me.

Five years ago, I took a road trip with my father from Wales to Berlin. My father, Hans, was the eldest son of a Jewish family. He escaped from Nazi Germany on one of the Kindertransports in 1939. The Kindertransports were a collective effort that took mainly unaccompanied Jewish children from Nazi Germany to the U.K. His mother managed to get him onto one of the last trains out of Berlin. He was 12. He traveled alone. He left his family behind. Some he saw again—most he didn’t. All his life he refused to talk about what had happened to him. He considered himself exceptionally lucky.

Our trip together followed his journey of escape in 1939, but in reverse. We drove from Wales, to Harwich, took the ferry to the Hook of Holland, went to Amsterdam and then stayed in Berlin.

In Berlin we found things that my father remembered, the house he grew up in, cafés he’d eaten in with his family, one of his father’s shops, the Tiergarten where he learned to ride a bike. We swum in a lake he had swum in as a child with his sister and his father and we visited the station platform he left Berlin from in 1939. We stood together in the spot where he said goodbye to his mother. Standing there together we both seemed to unfreeze slightly, to thaw a bit. No words were said but we understood that something was passing between us. We visited Berlin’s Jewish Museum and the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe. We made a trip to Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

My father had somehow communed with me and in so doing had allowed me to glimpse what had happened to him.

Memories came back to my father. They began to invade him so that in the hotel we were staying at, he screamed out at night. During the day he described what happened to him at school as his friends stopped speaking to him and inviting him to their parties, what happened to him during Kristallnacht when his father’s shops were destroyed, how his older sister left one day in February 1939—without warning, and where, he did not know. Despite the pain of his emerging memories, my father talked only of luck. “How lucky I have been,” he continually said. “Luck,” he kept repeating, “What luck”—his mantra throughout his life.

I knew that something powerful was happening during our trip though I could not articulate it. Writing about it meant I had to trace the impact of the traumatic event upon my father, to discover and then record what had happened to him and then I realized, with a sinking feeling, that I had to write about what had happened to me. I began to realize that I was writing about the way that trauma that happens to one person can pass down the generations, not as an abstract idea but as it actually happened. Things, I came to realize, had been secretly, and in silence, communicated to me. The word “commune” is one that became useful to me. My father had somehow communed with me and in so doing had allowed me to glimpse what had happened to him.

As I wrote about our journey together, I came to experience the language of our bodies. They were reacting to what was happening. The body has its own eloquence. I spent a long time describing what it felt like in these moments with my father, feelings of pressure, compression, heat, the sense of leaving my body, a clawing at my skin, immense stillness, a swirling of the mind, a feeling of strange inflammation in my both my hips and fingers.

Much of our trip together was spent in a kind of full-up silence. Writing about this silence—and about how one writes about that which is impossible to comprehend—became very important to me. It made me realize what we all know that fraught and full silences are impossible to describe yet contain profound meaning.

Tragedy is one of our oldest aesthetic forms—it’s ancient. I like to keep my work within its constraints as it is a suitable form for holding and containing inexpressible sorrows. It is a container where deepest feelings of catastrophe can be looked at safely. For this reason, tragedy is an optimistic structure. It illuminates the points where we can collectively learn, so that certain behaviors can be avoided in the future.

Until we went on the trip my father had suffered, for his whole life since the kindertransport, from vivid and disturbing nightmares. These involved him shouting out at night, moving around the bed, lashing out with his legs and arms. They also involved cleaning the house during the early hours of the morning, running taps, cleaning floors, polishing shoes. His nightmares consumed him. His physical restlessness marked him. It was impossible for him to rest even while sleeping. He was a tortured soul. After our trip to Berlin, he was able to sleep soundly for the first time. He relaxed. He died very peacefully nearly two years ago. It was night. I was with him. We were alone together. A gentle smile appeared upon his mouth. He wasn’t frightened at all.

__________________________________

The Berlin Shadow by Jonathan Lichtenstein is available via Little, Brown Spark.

Jonathan Lichtenstein

Jonathan Lichtenstein is Professor of Drama in the Department of Literature, Film, and Theatre Studies at the University of Essex. An award-winning playwright, Jonathan trained at Bretton Hall, and his work has been featured by the BBC and performed in theaters across the UK, as well as in Germany and off-Broadway. He lives in Wivenhoe, a village on the Essex Marshes, with his wife and three children.