Writing From Inside the Precarious Hunger of Childhood

Linda Rui Feng on the Stories and Books That Cracked Open the Possibilities of Storytelling

For a couple of years after undergrad, when I was adrift between job and school and sheepishly wondering if I might try my hand at writing, I became obsessed with an anthology edited by Lorrie Moore, titled I Know Some Things: Stories about Childhood by Contemporary Writers. It resonated with me in a way that began as a small hum but eventually agitated me into action, and only in retrospect do I recognize that it served as a kind of primer for me, or perhaps a yardstick. I read some of its stories so many times that the cadence of their sentences felt ingrained in my ear, such that to revisit them, as I do now, feels as comforting as wrapping a favorite sweater around me.

It was in this collection that I came across my first Alice Munro story (“The Turkey Season”), about a 14-year-old girl at her job as a turkey gutter. The protagonist has not yet entered the fray of adulthood and sexuality, yet her steely-eyed, no-nonsense observations about her co-workers deftly capture the messiness of all that she has not yet experienced.

This story was a small portal that eventually led me to one of my favorite books by Alice Munro, Runaway, a set of eight stories about young women progressively shedding their adolescent innocence, a metamorphosis that connects the stories so deftly that the collection almost feels like a set of linked stories.

What I love about Lorrie Moore’s anthology is that the stories don’t idealize childhood. They take us right up against the confrontation of children with darkness; they feature adults who threaten cruelty and violence toward others, but also to themselves, as in the unforgettable story “The Point” by Charles D’Ambrosio, in which an adolescent boy takes on a “priestly” role to walk drunken guests home from his house. It was also from this collection that I became entranced by the work of Charles Baxter, a master of subtext and distiller of the sublime from the ordinary.

The story “Gryphon” is taken from Baxter’s mesmerizing collection Through the Safety Net, and shows us how one boy’s outlook is changed, subtly yet irreversibly, by a substitute teacher whose two-day stint at his school ends with an ominous tarot card reading. Even on its own, “Gryphon” remains one of my all-time, desert-island favorite short stories, because I marvel at the way Baxter shows, step by infinitesimal step, the gradual yet inevitable transformation of the boy’s mindset.

Baxter himself calls the substitute teacher in the story “an ambassador from the land of imagination,” and says, “In the land of imagination, you think at first that it’ll all be peaches and cream: wonderful oddball facts and images and poetry—a big relief from the usual. But if you’re going to cast your vote for the imagination, you had better be ready for the darkness and craziness, because that’s going to be part of the imagination’s landscape, too.”

But even before I knew to seek out these writers’ larger bodies of work, before I even knew what I would write myself, I returned time and again to Lorrie Moore’s words in her short introduction to the anthology, in which she says: “As the most recently arrived to earthly life, children can seem in lingering possession of some heavenly lidless eye. Their appetite for observation is omnivorous and unsentimental, and their innocence, a kind of preternatural genius spent in the senses, spent in the hungry acquisition of knowing, is of natural interest to writers fashioning a record of human experience.”

I read some of its stories so many times that the cadence of their sentences felt ingrained in my ear.

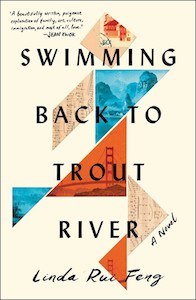

These words have stayed with me, and have been beckoning me ever since to join this endeavor of writing from inside that “hungry acquisition of knowing” which characterizes childhood. When I began my novel, Swimming Back to Trout River, the early story took shape in my head as a young girl’s determination to maintain her idyllic life and its ecology of relationships in her grandparents’ natal village in China, and to resist a momentous change thrust upon her: to emigrate to America to join her parents.

This single-minded determination to declare where she felt rootedness, to fight for what is near and dear rather than what is remote and abstract—this, too, feels to me like an essential, if also precarious, quality of being a child. I wanted to see the consequences of that resolve play out and reverberate in the rest of the novel: as the child asserts herself, it sends out ripples into the lives of her parents and ultimately unravel their own secrets and obsessions from their youths.

In the years my novel gradually went from living inside my head to finding its way onto the page, I began to understand that writing with the “heavenly lidless eye” necessitates a peeling back of the protective layers we encrust ourselves with over the years—a process that can be both liberating and fraught. I found other books written from inside childhood that cracked open for me possibilities of storytelling.

Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad is a novel that masterfully braids many point-of-view characters so that it emerges larger than the sum of its parts. Its most unforgettable chapter, “Great Rock and Roll Pauses,” is composed entirely of PowerPoint slides by a 12-year-old girl that illustrates the dynamics of her family which includes a brother with autism. I have rarely read anything that felt so astonishingly compelling.

The Road to San Giovanni by the fabulist writer Italo Calvino is a collection of essays he called “memory exercises,” and begins with an extended recollection of the enforced daily walk Calvino used to take with his agronomist father who wanted his son to follow his career path. With wending sentences that never seem to lose their momentum, Calvino the adult traces out the point from which his boyhood self saw his destiny diverge from that of his austere father. In these sentences that approximate a distillation from whatever memory-ether that follows us throughout life, the adult and younger selves often argued and jostled with each other right on the page. These works all made me ask myself: what power of dissent, if any, does a child wield in his or her powerlessness?

In my own novel, the ten-year-old Junie’s refusal to emigrate is a counterpoint to the immigration journeys undertaken by three adult characters—her father, mother, and an old friend of her father who is a talented musician. They each leave China at different times and for a different reason, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, encounter a different America.

As I was writing each strand of the narrative, it was always important for me to include something pivotal from each character’s early years, scenes that I felt would capture the combination of powerlessness and determination of having been a child.

In an interview, Edward P. Jones said, “I often say that one of the stories I’d like to write would have the beginning ‘We never get over having been a child,’ because that’s so much of where it all happens; it all begins there.” This is why stories written from inside childhood are worth going back to, again and again.

__________________________________

Swimming Back to Trout River is available from Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2021 by Linda Rui Feng.

Linda Rui Feng

Born in Shanghai, Linda Rui Feng has lived in San Francisco, New York, and Toronto. She is a graduate of Harvard and Columbia Universities and is currently a professor of Chinese cultural history at the University of Toronto. She has been twice awarded a MacDowell Fellowship for her fiction, and her prose and poetry have appeared in journals such as The Fiddlehead, Kenyon Review Online, Santa Monica Review, and Washington Square Review. Swimming Back to Trout River is her first novel. Visit LindaRuiFeng.com to learn more.