Writing Fiction About Fact: Using Historical Figures As Characters

On Michael Cunningham, George Saunders, and Other 'Literary Grave-Robbers'

Since the dawn of storytelling itself, authors have employed real life characters in their fictional work; think Shakespeare and any number of kings. The practice has ardent defenders and detractors. Many writers see opportunity, a way to use historical—or even modern—figures to draw readers into a story that they might otherwise overlook. Using real people allows novelists to anchor a reader in a very specific moment in time, to comment on their societal influence (or society’s influence on them), explore a mystery surrounding them, or consider a lesser-known, perhaps more human, side of an outsized public persona. Some critics find the idea wholly unnecessary when there are so many superb, compelling biographies. Writer and critic Jonathan Dee in a 1999 essay for Harper’s magazine went so far to deem it macabre: “literary grave-robbing,” he called it.

Detractors argue the practice is lazy. Writers of fiction are limited only by their creative power, they have the freedom to make up entire worlds. Thus, using a real life person in a novel seems like a failure of imagination. To an outsider, it may seem that using a real person as a character is letting history do much of the heavy lifting for you. After all, shouldn’t it be easier to make a person for whom we all have a common image jump off the page as opposed to an entirely made up person who has to live and breathe from scratch? Dee argues that “creating a character out of words and making him or her as vivid and memorable as a real person might be the hardest of the fundamental tricks a novelist has to perform.” If that’s true, would writing a real person into fiction make the writer somewhat of a . . . hack?

As someone who has written a historical figure into my own fiction (the formidable Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, no less), I can tell you the practice can be much more difficult than it appears. Creating a vivid version of historical figure is threading a very fine needle. You need to meet everyone’s agreed upon notions of this person while adding your own invigorating spark. They have to feel fresh but authentic, lived-in and in some way new. Often, figures that attract ongoing intrigue are shady, or we only know one side of them. As a reader, I find it thrilling when an author picks just the right figure, gives them real narrative purpose, and makes them come alive.

To that end, I wanted to celebrate some examples of the genre that have inspired me.

The Hours by Michael Cunningham

Cunningham, in his Pulitzer prizewinner, resurrects Virginia Woolf as one of three protagonists, only to drown her again in his prologue. But his portrait of Woolf is much more about living than dying. He lets us inside a beautiful, tortured mind, and crafts a story with sensitive and well-constructed insight into mental illness, expanding upon Woolf’s idea that sanity involves a certain element of impersonation. In creating two fictional women in two successive generations to stand alongside Woolf, he reveals the real tragedy may be that Woolf was simply ahead of her time. As a whole, we have become more forgiving of each other—and, in turn, ourselves.

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders

Given that Saunders has said he was inspired to write his story after hearing accounts of a grieving President Lincoln entering a crypt to hold his son Willie’s body, this could have come off as the most literal example of literary grave-robbing. Instead, it’s a heart-rending national ghost story and a beautiful meditation on loss and the human condition. Like the best books borrowing historical figures, Saunders not only gives us a fully-realized Abraham Lincoln, he opens our eyes to something surprising about our history and ourselves.

Leading Men by Christopher Castellani

Castellani’s novel opens with Tennessee Williams and his lover Frank Merlo attending a 1953 party thrown by Truman Capote in Portofino, Italy and, despite the high degree of difficulty, he pulls it off like a diver flawlessly entering the water with little splash. While the bulk of the story flashes forward and focuses on a fictional actress of Castellani’s creation, his interpretation of Tennessee Williams looms throughout. The brilliance in Castellani’s novel comes from his own ability to create tragic, Williams-esque heroes; even when Williams is missing from the action, his presence is felt in the writing.

A Piece of the World by Christina Baker Kline

Baker Kline paints a vivid portrait of Christina Olson, the subject of artist Andrew Wyeth’s haunting Christina’s World. Olson is not a celebrity or household name; she’s a historical footnote at best. When we meet her she’s a quiet, middle-aged woman, crippled by polio. Yet her image, twisted, reaching, crawling in the grass, has made an indelible impression on our culture. Wyeth said of his masterpiece, “The challenge to me was to do justice to her extraordinary conquest of a life which most people would consider hopeless.” Wyeth accomplishes that in a single image; Baker Kline breathes new life and creates a literary portrait to hang beside Wyeth’s. The beauty is, the book stands on its own.

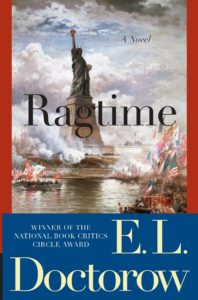

Ragtime by E.L. Doctrow

Ragtime is one of the great American novels beloved in part for the way it effortlessly weaves multiple historical figures into its sprawling plot, using them to comment on themes of fame and success at the dawn of the twentieth century. Harry Houdini shows up most prominently, reflecting on mortality and the afterlife. Financier JP Morgan and Henry Ford discuss automation and its effect on the American worker—something we still grapple with today. Anarchist Emma Goldman appears to challenge everyone’s ideas. Doctorow rejects absolutism for a more complex view of history. He alters details about his historical characters, even fabricating circumstances for them entirely. In doing so, he provides prescient commentary on the subjectivity of news and historical events.

We read to learn, to be entertained, transported, to have our eyes opened to something new. Drafting real life figures can be an effective tool in a writer’s arsenal in accomplishing those goals—so long as it is done with a healthy respect for the figure at hand.

Steven Rowley

Steven Rowley is the author of Lily and the Octopus and The Editor. His new novel, The Guncle, arrives May 25th from G.P. Putnam’s Sons.