I kept what became the epigraph of my novel—“pleasure disappoints, possibility never”—taped above my desk (the many desks, the many cities) throughout the writing process. It came from Kierkegaard’s Either/Or, in a section narrated by Johannes Climacus, the aesthete and pleasure seeker. A student of philosophy, I arrived at fiction through 19th-century existentialism, specifically Nietzsche and Kierkegaard, and ideas around freedom, despair, choice. Authenticity. These concepts served as the book’s initial buttresses as the story grew within it. Once it was strong enough to stand on its own, I stripped away the scaffolding.

The narrative guiding this novel, and what led to this particular epigraph, was born of a writing prompt from a French class (not even a writing course!), based on a poem by Baudelaire, roughly translated as “Be Drunk.” The poem commands readers:

You have to be always drunk. That’s all there is to it—it’s the only way. So as not to feel the horrible burden of time that breaks your back and bends you to the earth, you have to be continually drunk. But on what? Wine, poetry, virtue, as you wish. But be drunk.

The writing prompt: What intoxicates you? Many things, it seemed. As my list grew, I detected an underlying pattern that linked them: possibility. Indeed, with this book, it was possibility that allowed me to persist through freezing Iowa winters, long johns, endless grey sky, loneliness, through other people’s milestones so visible on Facebook while I languished in my apartment, the pages of this book taped to my walls as I sorted out its structure.

It was the possibility of success, not always entirely realistic, much of it guided by delusional optimism. Through this book was the possibility of mitigating pain. Of validation. Of asserting an existence.

Mine was an existence that needed asserting for reasons that lived on both a macro and micro level. First, the collective cultural, as a Palestinian. Being Palestinian means having your most basic rights repeatedly denied, including the right to statehood and self-determination. It means living in a state of perpetual resistance. Though I grew up in the diaspora, I feel no less implicated by that threat.

Instead, the disconnect makes attaining a sense of home and validating an existence that much more urgent. Once, in the text of a piece I’d written, the editor struck the word Palestine and wrote beside it, “Palestine doesn’t exist.” I felt pain and anger at this. Who was she to say? What does it mean to exist without external validation, I wondered. I rejected the change and ended up working with another editor.

Possibility is a safe space from which to love.

Then, on a micro level, as a bisexual woman in a household and culture where existing as such was unfathomable, and therefore unacceptable. To validate such a way of being in the world by locating it within a protagonist who bore these identity markers, with all of her flaws, and who demonstrated agency, problematic as her choices and behavioral patterns could be, felt both necessary and soothing. It felt truthful. More than likable, the heroine had to be authentic.

Authentic. What does it even mean? For Kierkegaard, it means becoming what one is. In the case of my protagonist, becoming who she is means existing just as she does, uncensored and unstifled. The character is messy. She embodies inter-lapping and intersecting qualities. But my refusal to tidy her by reconciling her many internal contradictions or over-steering her, allowed her the possibility of arriving someplace authentic.

Indeed, she is drunk with the possibility of becoming, of actualizing on the page. Along with it is the possibility of approval, of love. Initially, love’s possibility is privileged over its actuality, and that’s precisely the point. Possibility is a safe space from which to love.

It is perhaps the most detrimental and defining contradiction she embodies: wanting romantic love while remaining at a distance from it, thereby preventing it. She is her own greatest obstacle to getting what she wants. And while she never achieves the full approval that she longs for, at least not externally, but she at least needs it less.

For a character so wounded, parental relationships fraught, there was also the possibility of compassion. Of recognizing that for her parents, both immigrants, the wounds of an existence denied as Palestinians who had grown up under occupation cut that much deeper, as did the effects, which sometimes bore out in toxic ways. There was the possibility of processing a mother’s trauma in order to understand, and forgive. The possibility of transcending anger and arriving at parental love.

Above all, there was the possibility that by writing about an ache that transcended the Palestinian—that of wanting what you can’t have, of longing for things in the distance—I could subvert a dominant narrative of Arabs, of Muslims, of Palestine. I could break down a resistance to images that contradict those in the media: images of violence, oppression.

By transcending these limitations and misperceptions, by enacting messiness, there was the possibility of existing without apology or shame, of living a life un-redacted, with entitlement unto itself and no need for external validation.. “The easiest thing to lose is oneself.” Another of my favorite Kierkegaard quotes. Indeed, through the process of writing this book was the possibility of self-love.

_________________________________________

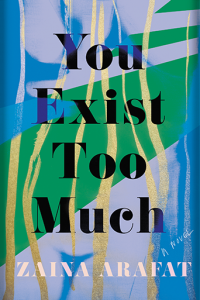

Zaina Arafat’s novel You Exist Too Much is available now.

Zaina Arafat

Zaina Arafat is a Palestinian American writer. Her stories and essays have appeared in publications including The New York Times, Granta, The Believer, Virginia Quarterly Review, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, BuzzFeed, VICE, and NPR. She holds an MA in international affairs from Columbia University and an MFA from the University of Iowa and is a recipient of the Arab Women/Migrants from the Middle East fellowship at Jack Jones Literary Arts. She grew up between the United States and the Middle East and currently lives in Brooklyn.