Women in Publishing 100 Years Ago: A Historical VIDA Count

Representation and Gender (Im)Balance in 1916

There was no suffrage for women 100 years ago, and there was certainly no VIDA Count—no one was checking to see if the major book reviewers of the day were reviewing books with any kind of equity. It wasn’t until 2009 that VIDA was founded to combat major imbalances in the coverage of male and female writers in top-tier literary journals with raw research and simple counting.

So I decided to look at the coverage that the New York Times Book Review (then called The Review of Books) gave to male and female authors, respectively, 100 years ago in 1916. I battled ProQuest and the Times Machine to look at every issue and marked down the gender of each author reviewed, googling the Lindsays, Ashleys, Danas, and Bernadottes just in case. I included illustrators, translators, and editors of compilations in my count to be as inclusive as possible. The reviews were uncredited, so I didn’t note the authors of those; I’m guessing it was disproportionately men writing the reviews. I did not look at the content of the essays unless they were a comprehensive review which listed the publisher and price of each title. A few pages were illegible, so a few reviews were lost.

Here is what I found:

There were 1,392 books reviewed in 1916.

1,085 of those books were by men.

304 were by women.

The gender of three of these writers was unclear. Two of them were anonymous, and the reviewer did not comment on their gender one way or the other. In a complimentary review of a book called Blind Sight by a writer named B.Y. Benedall on January 9th, the reviewer, instead of defaulting to Mr., writes, “Mr. or Miss or Mrs., as may chance to be.” And then refers to Benedall as “he” several times.

The only other time I noticed any kind of preciousness about titles was in a review of M. Macdermott Crawford’s Peeps Into the Psychic World, a relatively unusual title given that women mostly appeared in the Book Review‘s pages, and that I didn’t see another supernatural title the whole of the year. The review went out of the way to speculate on her marital status: “Miss—or is it Mrs.?” Very important to the quality of the book, I’m sure.

And I was a little offended on behalf of Katrina Trask, whose The Invisible Balance Sheet (which sounds like a well meaning Tumblr post) was reviewed on the front page with a lovely illustration identifying her as just… Mrs. Spencer Trask. Mrs. Humphrey Ward, one of few women to independently publish a book on the war, definitely preferred her husband’s name, as she used it to write screeds against women’s suffrage.

Writers of color were more difficult to find and categorize, but that’s mostly because The Review of Books had shamefully few of them. I noted only seven books by writers of color out of the thousand plus reviews.

Four of those books were relatively prominent: lengthy positive reviews for St. Nihal Singh’s The King’s Indian Allies and Yono Noguchi’s The Spirit of Japanese Art in the July 23rd issue. Sir Rabindranath Tagore was reviewed and even illustrated twice on the cover of the Book Review, including a rave review for his landmark The Home and the World, one of the few books of extant relevance I encountered.

But among those seven books by people of color, there was not a single work by a black writer, Nor did a single work by a woman of color appeared in the New York Times Book Review in this year. Every single female writer in the above count was white.

Obviously, the omission of these writers is not an indication that people of color did not publish any works of literary significance. Carter Woodson began publishing The Journal of African American History, then The Journal of Negro History, in January. Many future scribes of the Harlem Renaissance, including Sutton Griggs, William Pickens, Fenton Johnson, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, James Corrother, and John Edward Bruce, published works that went unnoticed by the Book Review.

A particularly interesting omission is Rachel, first known as “Blessed Are The Barren”, a drama written to protest lynching. Angelina Weld Grimke, an African American lesbian teacher, poet, and playwright, produced Rachel for the NAACP as a statement against lynching in response to the previous year’s genocidal blockbuster Birth Of A Nation (though it wasn’t published as a book until 1920…at which point the Review also declined to review it.) Another major work of dramatic art by a white lady that went ignored was Trifles by Susan Glaspell. It’s in a bunch of anthologies as a way to discuss sexism in literature; I have read at least eighty student papers about as a community college writing tutor.

The weekly review of the “Latest Works Of Fiction” was where a disproportionate amount of books by women could most consistently be found every week. Several women translated great works of Russian literature, but of course they weren’t the focus of the review. Science fiction by people not named H.G. Wells didn’t make much of an appearance. It’s not that women never wrote about other topics. A couple examples included a biological text titled “Man: An Adaptive Mechanism”, edited by Annette Austin. Orie Latham Hatcher of Bryn Mawr wrote a practical guide to producing Shakespeare. There were several female illustrators of books about nature, as well as books about the domestic arts: cooking, sewing, and gardening. Travel saw more equitable coverage of books by women. But overall, non-fiction was dominated by men.

World War One was a major focus of all news media in 1916, which extended to the Review, which published several lengthy reviews of recent war-related publications every week. Women weren’t totally shut out: Ellen Key’s War, Peace, and the Future had a lengthy review on October 22 edition, and there were a couple volumes on nursing, too. There were not lady generals, as a general rule. In most cases—and this is a qualitative rather than quantitative observation—column inches for non-fiction books went to men with Qualifications, in war and other fields.

This is a qualitative rather than quantitative claim: I observed many more non-fiction works written by men in a much range of topics: academia, military, religion, medicine, and politics. Oh, and also poetry. And I noted only two or three women with specific professional designations like those of the decorated military authors whose biographies would run five lines long in bold print, and I already mentioned Orie Latham Hatcher. There was also Emma Matteson, an instructor at the George Peabody College for Teachers and a technical high school, who wrote about the technical aspects of food. E.R. Thayer, the Art Director of the Decorative Designers, wrote a book called When Mother Lets Us Draw. Helen Marot was identified as a member of Local 12.646 in a book about the labor movement “in a manly fashion,” in case you forgot this was 1916.

Women who published often found success with a writing partner. Helen Gleason managed a coup: she had a book called Golden Lads about Manly War published, and reviewed on the front page of the supplement. Undoubtedly, having her husband Arthur helped escort the book into serious consideration, and the reviewer made sure to note immediately that she only wrote one article in the book about the Red Cross, but surely she helped her husband. In another case, two sisters, Jane and Mary Findlater, co-authored a book about family life in England called Content with Flies; a review of the book on December 10 cited these very simple lifehacks:

The cover of the New York Times Review of Books was as disproportionately dominated by men, with 102 works by men or male authors featured or pictured on their front page and only 24 women. But women still did succeed on that level. In reviewing her “Life and Gabriella,” the Review wrote that Ellen Glasgow “established a right to a place in the front line of contemporary novelists.” The next month saw a double-lady cover: May Sinclair’s The Belfry and Gertrude Atherton for Mrs. Balflame, a novel mostly forgotten except for the first line, “Mrs. Balflame made up her mind to commit murder,” which was dissed independent of author or title in this 2016 Electric Literature article. Margaret Deland was pictured on the front page of the review twice, once for an explicitly feminist novel called “The Rising Tide”. Mary Roberts Rinehart appeared twice for both fiction and non-fiction works, first appearing with full-on crazy eyes next to a horse for her book about National Glacier Park in June, and then wearing a fly hat as a part of a preview of new books of the season in the fall.

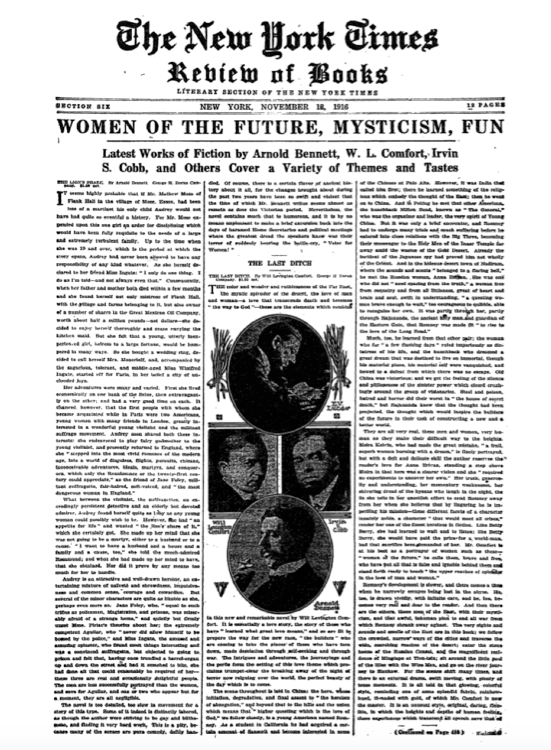

But despite these successes, women were shut out of the front page at about the same rate they were shut out of the other pages of the supplement. Sometimes this led to some hilarious irony, as with this cover that tantalizingly promised “Women of the Future, Mysticism, Fun” and gave us four boring looking dudes:

So many of the books I read were forgotten; it was a strong rebuke to my daydreams of my books getting raves in the Book review and then also being taught in classrooms 100 years later. Critical attention and long-lasting relevancy just don’t go together the way we think they will. Literature has a wild and weedy afterlife, and even a big serious literary hit can be as ephemeral as a tweet.

So many of the books I read were forgotten; it was a strong rebuke to my daydreams of my books getting raves in the Book review and then also being taught in classrooms 100 years later. Critical attention and long-lasting relevancy just don’t go together the way we think they will. Literature has a wild and weedy afterlife, and even a big serious literary hit can be as ephemeral as a tweet.

Roughly, one out of five books reviewed by the New York Times Review of Books in 1916 was authored by a woman. There were at least two women in each issue of the hallowed supplement, and on average more than five. This is, frankly, better than I expected. I’m also glad to see that the Book Review has cleared that low bar in every year since the VIDA Count started; while no more than 35% at most of books reviewed from 2009-2012 were by women, they have had significant improvements in 2013 and 2014. It has gotten better, not just over the last hundred years but in the last five too.

But I was sad to note that many literary organizations can’t even beat the Book Review from 100 years ago. In 2014, only about one in five books reviewed by The Nation were by women. The same goes for the London Review of Books. Though The Times Literary Supplement, The New Republic, and Harper’s did just slightly better, they still couldn’t manage to include more than one woman out of every four authors reviewed in 2014.

The necessity of the VIDA Count is in improving what has been etched into our expectations of who is most worthy of critical attention at our highest levels. If it had been started in 1916, perhaps we wouldn’t need it today. But as we need the VIDA Count to pressure publishers into equality today, I expect that it will still be relevant in yet another 100 years.

Rachel McCarthy James

Rachel McCarthy James was born and raised in Kansas, the daughter of baseball’s Bill James and artist Susan McCarthy. She graduated from Hollins University in Roanoke, VA, where she studied writing and politics. Her first nonfiction book, The Man from the Train, was written in collaboration with her father and published in 2017. She lives with her husband Jason and pets in Lawrence, KS.