William Styron’s Misguided Meditation on History

Chris Tomlin Asks Who Can Claim the Story of Nat Turner

In an Atlantic essay last month, Alexandra Styron responded to current literary debates over cultural appropriation (notably those concerning Jeanine Cummins’ novel American Dirt) by recalling the controversy that surrounded her father’s 1967 book, The Confessions of Nat Turner. Reminiscent of early hype about American Dirt, Styron’s Confessions received rave reviews upon publication. The Nation’s Shaun O’Connell called it “A stunningly beautiful embodiment of a noble man, in a rotten time and place, who tried his best to save himself and transform the world.”

No one was more admiring than literary critic Philip Rahv in the New York Review of Books: According to Rahv, Styron had surpassed William Faulkner in “ability to empathize with his Negro figures.” His book was “a radical departure from past writing about Negroes.” It fulfilled its author’s ambition “to know the Negro.”

African American critics, on the other hand, were appalled by this white author’s presumption in representing his book as the famous slave’s autobiographical narrative. The hapless condescension of reviewers like Rahv helps explain their central complaint, summarized in the title of an essay by Vincent Harding: “You’ve Taken My Nat and Gone.”

In her essay, Alexandra Styron defends her father, though not uncritically. Her advice? As long as you root your narrative in truth, and check your facts, you shouldn’t be afraid to invade alien territory with imagination and conviction.

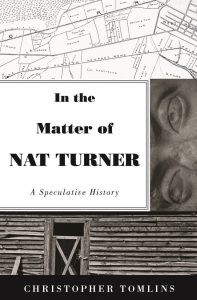

I do not know Alexandra Styron, though I have reason to be grateful to her for a small but nonetheless significant gesture of assistance she offered me a year ago as I was completing my own book about Nat Turner. Recently published, that book—In the Matter of Nat Turner: a Speculative History—begins with its own assessment of William Styron’s Confessions.

Now, there is no doubt that William Styron did indeed appropriate Nat Turner; nor was he shy about saying so. “I supplied him with the motivation,” he told one audience shortly after the book was published. “I gave him a rationale. I gave him all the confusions and desperations, troubles, worries.” His purpose was not ignoble—Styron wanted to make the man and his motives comprehensible. But he did not follow his daughter’s advice to root his narrative in truth, or to check his facts, and as a result his book became mired in controversy.

When critics challenged his creative imaginings of Turner and of slavery, Styron would cite his research, his mastery of facts and sources.William Styron had no real desire to understand Turner on any terms but his own. Styron wanted to rewrite the historical Turner that appeared in the 1831 pamphlet “The Confessions of Nat Turner” by Virginia attorney Thomas Ruffin Gray. That Turner, Styron believed, was “a ruthless and perhaps psychotic fanatic, a religious fanatic,” and this was a figure with whom he wished to have nothing to do. “I didn’t want to write about a psychopathic monster,” Styron said.

So, claiming “a writer’s prerogative to transform Nat Turner into any kind of creature I wanted to transform him into,” Styron invented his own Nat, inspired by “subtler motives” than those he thought were on display in the historical record, motives that he thought would enable the man to be “better understood.” He would discover that he was wrong.

There is an inevitable tension for anyone writing on a historical subject between historical research and creative imagination. Styron acknowledged as much. “During the narrative that follows I have rarely departed from the known facts about Nat Turner and the revolt of which he was the leader. However, in those areas where there is little knowledge in regard to Nat, his early life, and the motivations for the revolt (and such knowledge is lacking most of the time), I have allowed myself the utmost freedom in reconstructing events—yet I trust remaining within the bounds of what meager enlightenment history has left us about the institution of slavery.”

Simultaneously, Styron alluded to his embrace of a philosophy of history that, in effect, overcame the tension between fact and creative imagination that he acknowledged. “The relativity of time allows us elastic definitions: the year 1831 was, simultaneously, a long time ago and only yesterday. Perhaps the reader will wish to draw a moral from this narrative, but it has been my own intention to try to re-create a man and his era, and to produce a work that is less an ‘historical novel’ in conventional terms than a meditation on history.”

Styron’s desire to escape the low-earth orbit of moralistic storytelling and the “historical novel” in favor of a narrative that played with “the relativity of time” is clear. Unfortunately for him, he would find it impossible to explain precisely what he meant by “a meditation on history,” or how it had helped him overcome the fact/imagination tension, or how it gave him a standpoint different—more serious, more worthy of respect, more authentic—than that of the historical novel.

As a result, Styron became stuck in an increasingly petulant defensive crouch. When critics challenged his creative imaginings of Turner and of slavery, Styron would cite his research, his mastery of facts and sources. When they challenged his mastery of facts and sources, Styron would cite his creative imagination.

Styron struggled for the next 25 years to articulate what his “meditation on history” meant because, being neither a philosopher nor a historian, he actually had no idea what it meant, and so took his cue from the views of whatever authoritative and apparently supportive voice—historians, scholars of literature, sympathetic critics—he happened to encounter. Although he stubbornly insisted on the integrity of his depiction, by 1992 Styron seemed resigned to the conclusion that no “true” Turner could ever emerge, whether from his pen or anyone else’s. Turner “utterly evaded a consistent portrayal.” He “was truly a chameleon.”

Like William Styron, my own book In the Matter of Nat Turner attempts a meditation on history. But unlike Styron I am a historian. This means I believe that an actual existing Nat Turner is accessible in remnants or traces that one must attempt to comprehend, a Turner with whom it is possible to communicate if one listens for him and to him with all the powers one can muster.

William Styron was hardly the first white man to claim that Nat Turner was his property.This Nat Turner is something other than the plaything of an authorial imagination. It is a revenant, a once-was that lives on, a remainder that can be recognized. Applying Alexandra Styron’s criteria, I have taken Nat Turner on with imagination and conviction, believing that my facts are right and that my narrative of him is rooted in truth.

My narrative of Nat Turner takes William Styron’s errors as its point of departure. His errors were shallow; they were the errors of a novelist who demanded an imaginative right to take possession of his subject and do as his artistic fancy dictated. What resulted was irresponsible, but William Styron was hardly the first white man to claim that Nat Turner was his property. After all, merely in his own short lifetime he had had four legal owners and as many as seven actual “masters.”

Styron’s ambition, however, was deep, and orthogonal to his demand that he be accorded a fiction writer’s license. It was to escape altogether the fictive terrain of the novel for a serious attempt to re-create a past, to stand by that re-creation as a philosophically valid exercise, and to propose that the exercise of re-creation was of moral significance in Styron’s own present.

“In the back of my mind I had hoped that whatever light my work might shed on the dungeon of American slavery, and its abyssal night of the body and spirit, might also cast light on our modern condition.” Here was a sign that Styron indeed wished to assume responsibility for what he had done because he believed in what he had done. I think he failed, but I take his attempt seriously.

I also believe in what I have done. My own “realistic portrait” of Nat Turner includes both the inevitable (there is no gainsaying the violence of the massacre he led) and the unexpected (but why did it occur?) Rather than avoid the “religious fanatic” that so repulsed William Styron, I am fascinated by him—faith, in my view, is the key to his motivation.

Above all, however, I want to affirm Styron’s instinct that pondering the relativities of time is essential to anyone—novelist or historian—who aspires to write about the past. Why? Because Faulkner had it right. The past is not past. The past tugs at our elbow, it seeks our attention.

As Walter Benjamin once wrote, the past is “an image which flashes up at the instant it can be recognized.” But we must be attentive to it, for the past is vulnerable to our carelessness. “Every image of the past that is not recognized by the present as one of its own concerns threatens to disappear irretrievably.” That’s why history matters. And that is something William Styron got right.

__________________________________

Christopher Tomlins’ book In the Matter of Nat Turner is available from Princeton University Press.