Despite the success of The Weavers, a New York City-based quartet, folk music was still largely a bottom-up phenomenon in the early 1950s, driven by small clusters of teens and twenty-somethings in song circles, regional folk music clubs, square dance societies, and progressive organizations. Big record companies hadn’t yet found a way to reliably monetize folk music, nor were they especially trying to at that point.

With the Communist scare in full swing, having already ruined or dampened the careers of performers like Pete Seeger, Josh White (who voluntarily testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee), and Burl Ives (who testified and named names), it would have been hard to fathom who would take up the call in their place. That it was a black woman with natural hair, barely a year removed from picking up a guitar for the first time, is remarkable. Then again, Odetta was brimming with such talent that she would have been hard to ignore.

She began generating buzz in the overlapping worlds of folk music and progressive politics by the end of 1952. At the hootenanny in Topanga Canyon, Seeger had become an instant fan. Although his star was then dimming because of the McCarthy-era witch hunts, he remained a force in folk music, and he began spreading the word about Odetta wherever he went. “She was astonishingly strong and direct and wanted her songs to help this world get to be a better place,” he recalled.

Whatever the extent of Odetta’s shyness or self-hatred—and it seems to have been quite severe during her early years—she fought through it. Still unknown in early January of 1953, she performed before an audience of 1,300 people during a meeting of the Southern California Peace Crusade at the Embassy Auditorium on Grand Avenue in Los Angeles. The group was a local branch of the American Peace Crusade, another organization that would face accusations of being a Communist front.

Speakers that night reported on the recent Peking Peace Conference, presenting favorable reports about Communist China and charges (disputed to this day) that the United States was employing germ warfare against North Korea. “Oletta [sic] Felious, young Negro singer, thrilled the Embassy audience with songs of peace,” reported the next day’s Daily People’s World, a Communist newspaper published in San Francisco. Misspelling aside, it was her first write-up as a folk singer.

That meeting, and Odetta’s performance, would later draw the attention of the House Un-American Activities Committee, though there’s no evidence the committee ever pursued Odetta directly and she was never called to testify. Very early in her career, still feeling her way, she avoided saying anything overtly political on stage, preferring to let her music do her talking, which may have saved her a trip to Washington.

In June, with a few more gigs under her belt, Odetta returned to the Embassy, this time to sing in front of a crowd of 2,000, as the opening act in a concert by her hero Paul Robeson. “He had heard about me on the grapevine,” Odetta recalled, and Robeson had asked for her to appear, a passing of the torch to a new generation of black radical singers, though neither could have fully known it at the time. Robeson sang “Old Man River,” “Water Boy,” songs in Yiddish, and “American working class songs,” according to the Daily People’s World. “Odetta Felius [sic] opened the program with songs and guitar accompaniment,” the paper said.

Although the concert was advertised as benefiting local Negro causes, it took place only five days before the Rosenbergs’ execution, when left-wing groups were in a fever pitch trying to convince President Dwight Eisenhower to issue an eleventh-hour pardon. It’s highly likely that Robeson addressed the situation during the show. Odetta, in fact, recalled it later as a benefit concert for the Rosenbergs, which is doubtful, considering that the Communist newspaper failed to mention it. “It was the only time my knees shook,” Odetta remembered, although that too seems unlikely given her early problems with stage fright. She would later take “Water Boy” and make it one of her signature songs.

However Odetta felt about Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, she later said the FBI had kept a file on her, which “likely came out of [my] involvement in collecting signatures to save the Rosenbergs.” It’s not clear whether Odetta ever saw an FBI file. Whatever its contents, the FBI appears to have destroyed it in the 1990s.

It wasn’t only Odetta’s selection of material that set her apart from many other white folk singers in the early 1950s. It was also her extraordinary interpretive ability.By the time of the Robeson concert, Odetta had already gone to San Francisco to visit Jo Mapes and her daughter, Hillary—Odetta’s goddaughter—who had been born the previous year. The real beginning of Odetta’s professional career came when she and Mapes took in a show at the Hungry I, a bohemian basement club on San Francisco’s Columbus Street run by a flamboyant former concert violinist named Enrico Banducci. The club would later become a launching pad for envelope-pushing comedians, including Mort Sahl, Lenny Bruce, Woody Allen, and Dick Gregory. But on this particular night, a young balladeer named Nan Fowler graced the stage.

Convinced of Odetta’s blossoming talents, Mapes decided that her shy friend needed a bit of a push if she was going to get paid for her singing. At one point, Mapes excused herself from the table and, without telling Odetta, went to talk to Banducci, informing him that “there was a folk singer in the audience who is on tour.” Banducci fell for the pitch and invited Odetta to sing a few songs. On the spot, he offered her a job.

Odetta returned to Los Angeles, quit her housekeeping job, and moved up to San Francisco, living at first with the Mapeses. When she reported for work at the Hungry I, however, she ran into a roadblock: the club’s regular headliner, a black folk singer named Stan Wilson, refused to share a bill with her, perhaps out of a fear of being overshadowed. Odetta was relegated to Wednesday nights, Wilson’s one night off, earning $10 a week—not even enough to join the local musicians’ union.

She eventually found another gig at a jazz club called Cable Car Village at California and Hyde streets. When the smooth-talking emcee tried to get Odetta to add extra sets on the house, she refused—she’d performed for too many union groups by then to take that kind of treatment sitting down—and the engagement ended after just three nights. But sitting in the crowd for one of those shows was Peggy Tolk-Watkins, owner of a new club called the Tin Angel, who offered Odetta her first steady job.

The Tin Angel had just set up shop in a converted warehouse across from Pier 23 on the Embarcadero, the San Francisco Bay waterfront that had once been the region’s shipping and transportation hub. Embarcadero means “place to embark” in Spanish, so it’s a fitting starting point for Odetta’s career. The piers, ferry boats, and short line railroad that once gave the waterfront life had fallen into decline following construction of the Golden Gate Bridge and the migration of shipping traffic across the Bay to Oakland. But the trains still ran on the tracks outside the club, its whistles providing an unsolicited counterpoint to the music emanating from the stage.

Tolk-Watkins, a lesbian poet, painter, and raconteur, is remembered as one of the real characters of North Beach bohemia. She drove to work in an old Ford sedan covered in pink and blue polka dots and was rarely without a cigarette in one hand and a martini in the other. She painted the Tin Angel’s walls red, blue, and green and decorated the club with assorted kitsch, artwork, and a player piano, giving it a decidedly campy feel. She’d pilfered the club’s namesake mascot, a two-and-a-half-foot-tall tin angel, which hung over the club’s door, from a defunct church in Brooklyn, New York.

Odetta opened at the Tin Angel on August 25th, 1953, a Wednesday. It’s here, from witnesses, music reviewers, and a live recording from the period, where we begin to get, for the first time, a sense of her fledgling stage act and the extraordinary impact it had on her audiences. Her repertoire already included work songs (“John Henry,” “No More Cane on the Brazos”), spirituals (“Children, Go Where I Send Thee,” “I’ve Been ’Buked and I’ve Been Scorned”), British ballads (“I Know Where I’m Going”), and songs from Lead Belly (“Rock Island Line”) and Woody Guthrie (“The Car-Car Song”).

It wasn’t only Odetta’s selection of material that set her apart from many other white folk singers in the early 1950s. It was also her extraordinary interpretive ability. She could evoke a small child asking a parent a million bedtime questions or a convict singing while toiling on a road gang and do both equally convincingly. Her deep contralto, especially on songs about black prisoners or railroad workers or forlorn slaves, seemed to roar from the depths of her being.

Her rendition of “Take This Hammer,” set to driving guitar, built tension so dramatically that by the time she ended the song, interspersing verses with guttural cries to mimic the crack of a nine-pound hammer, her listeners could actually begin to feel the pain and sweaty exhaustion of a convict laborer.

Take this hammer—hah!—and carry it to the captain—hah!

Tell him I’m gone boys—hah!—tell him I’m gone

The force of her singing contrasted, in an almost bewildering way, with her bashfulness on stage. Odetta’s spoken introductions to songs, delivered in a near whisper, came across almost apologetically. In fear of the audience, or engaged in an inner struggle against her sense of inferiority, she sang with her eyes closed beneath a short halo of natural hair.

One reporter, who showed up a bit later during her Tin Angel run, described a typical scene: “The large woman came out of the back room marked ‘private’ and walked between the scarred tables onto the stage. She sat on a stool, tuning her guitar . . . her eyes downcast. ‘This is the story of a man and a machine. The man’s name was John Henry,’ she spoke so softly . . . barely audible.” But after she started to sing, “[a]ll of a sudden the room was filled with a voice so magnificent and powerful . . . beyond any description.”

That snapshot is echoed by Pauline Oliveros, who went to Odetta’s debut performance and later became a noted avant-garde composer. “She was so very modest, almost self-effacing in her presentation, but her voice was so very powerful,” Oliveros recalled decades later, the memory still intense. “So when she sang she was really transformed from this young person who seemed almost reticent to present herself.”

Jo and Paul Mapes were there too. Once again, without Odetta’s knowledge, Jo had seen to it that her old friend got some attention. Jo had dialed up the San Francisco Chronicle and one of its music reviewers, Robert Hagen, had picked up the line. “There’s going to be a new singer” and “you must go down and hear her,” she told him. Hagen arrived a bit late, as Odetta was in the middle of shouting a cappella the prison song “Another Man Done Gone,” with just her hand claps keeping time.

Hagen was so impressed that he invited her to his office the next day to find out more about her. When Odetta showed up, wearing the large hoop earrings that would become one of her trademarks, he was surprised to learn that she hadn’t arrived straight from Alabama but had actually grown up mostly in Los Angeles.

His review appeared in Friday’s paper. “After hearing her sing ‘Why Can’t a Mouse Eat a Street Car’ and such folksy items as ‘I Was Born Ten Thousand Years Ago’ and ‘You Gotta Haul That Timber Before the Sun Goes Down’ in a low-down voice that sounded like an impossible amalgamation of Bessie Smith and Lead Belly, I was permanently convinced that Odetta is that rare but happy occurrence in the music business—a natural.” He described her as looking like a young Bessie Smith, “if she had worn a crew cut.”

If attention was Mapes’s goal, she succeeded admirably. By Saturday night, the club was packed to the rafters for Odetta’s 9 p.m. show—a terrifying prospect for a stage-shy singer. “I drove up, I got there, and I looked into the door, and I saw all those people,” Odetta recalled. “Scared me half to death. I turned around to walk back to the car.” But she steeled herself and snuck into her dressing room, literally a broom closet.

It just so happened that Herbert Jacoby, co-owner of the posh Blue Angel nightclub in New York, was vacationing in San Francisco and had gotten wind of the glowing review in the Chronicle. He decided to see what the fuss was about. Jacoby, a gay Frenchman with a long, birdlike nose, knocked on the broom closet after the show. “We’d like to have you at the Blue Angel someday,” he said.

Odetta hadn’t heard of the famous club, so her nonchalant reply—the equivalent of “Sure, sounds great”—might have come off as quiet confidence. A week later, Jacoby called Tolk-Watkins and told her they had a sudden opening. Could Odetta fill in? Barely weeks into her professional career, she was headed to New York.

The Blue Angel was a swanky after-theater club on East 55th Street with a red carpet at the entrance, a beautiful hatcheck girl, and a main room with pink leather banquettes and walls of gray tufted velour. (Lenny Bruce was said to have likened the decor to the inside of a coffin.) Jacoby and his partner, Max Gordon, made sure audiences were racially mixed, an uncommon feature in the early 1950s; white and black performers were equally welcomed and treated well, largely due to Gordon, who often booked black singers into his downtown Village Vanguard before moving them to the uptown venue. By the time of Odetta’s appearance, Josh White, Pearl Bailey, and Harry Belafonte had already had successful runs at the Blue Angel. “Oh, I had graduated from the deep dishmop sink at the Tin Angel to a real dressing room and this place!” Odetta remembered. “I mean, it was a classy jernt!”

When Harry Belafonte saw Odetta at the Blue Angel, he was astounded. “From the very beginning, she was just an absolute marvel,” he recalled.She debuted at the Blue Angel in the middle of September. She made no changes in her act for her nattily attired new audience, performing a mix of work songs, spirituals, and children’s songs, and attracted immediate attention, not all of it for her singing. Billboard’s reporter called her “a kinky-haired, pleasant, round-faced, chubby gal.” Indeed, early in her career, writers would wear out thesauri describing her hair and weight. Aside from the superficiality of the entertainment press, whose mostly male reviewers often reduced women to the sum of their measurements, none had come upon a black female with natural hair.

The put-downs quietly trampled Odetta’s soul, but she wouldn’t say so publicly until much later. This reviewer nevertheless concluded that she showed considerable potential: “There’s a peculiar quality in Miss Felious’s voice that should interest record people. Audience reaction was only tepid. But this could change, once the nervousness and minor amateur traits are eliminated.”

The gossip columnist Walter Winchell weighed in too. “The Blue Angel’s new stardust is a blues thrush named Odetta Felios [sic]. She landed in N.Y. after being ‘discovered’ in a San Francisco spot on her 2nd week in Show Biz.” Winchell was far from alone in flubbing her last name. Robert Dana of the New York World Telegram and Sun, calling her “Miss Felois,” described Odetta as a “buxom Negro lass” and pronounced her “probably the most exciting folk singer to hit town since Harry Belafonte switched from bop to folk tunes.”

One night, Jacoby brought Belafonte to Odetta’s dressing room. If the meeting was memorable for Odetta—she recalled her mouth nearly agape at the sight of him—it was equally so for Belafonte. He’d started out as an actor in the mid-1940s, then begun crooning standards like “Pennies from Heaven” and “Stardust” with a jazz band and recording Tin Pan Alley ballads with an eighteen-piece orchestra. By the early 1950s, his movie career had just begun to take off, and he’d started recording folk songs like “Shenandoah,” but as a singer, he still channeled Bing Crosby more than Lead Belly. Down-Beathad dismissed him as “synthetic in folk singing.”

When Belafonte saw Odetta at the Blue Angel, he was astounded. “From the very beginning, she was just an absolute marvel,” he recalled. “She was such an imposing figure. She was very majestic, and then when she opened her mouth, out came that voice, which was unlike any other anybody had ever heard.”

__________________________________

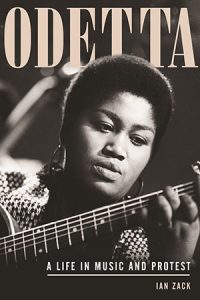

Excerpted from Odetta: A Life in Protest and Music by Ian Zack (Beacon Press, 2020). Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press.