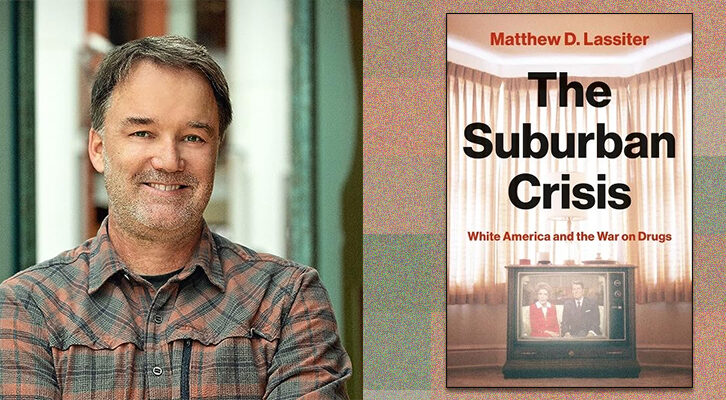

William Gay Was Never Too Busy for Life’s Smaller Moments

Sonny Brewer Remembers His Friend, a Master of the Southern Gothic

William Gay was a good man. And they aren’t that easy to find. My great uncle got specific and said a really good man was one in ten thousand. He was a Harvard-trained minister who spent 40 years in the pulpit. He was, however, pulling a thread in his clerical cloth hoping to impress me with an opportunity to be somebody just by being good.

Confucius talked about the idea of a good man. He said a good man is kind, has integrity, doesn’t need much, and is willing to put himself at the disposal of other people. But more, while being an archetype, he is not rich or a politician, not a ballplayer or a celebrity—just somebody who understands others, and counts relationships with family and friends above all else. The philosopher said you could spot a good man in a crowd. Something about him, even at a casual glance, welcomes your trust. You don’t have to wear a robe and chant mantras to detect something different in a good man.

The night I met William Gay, we were in a bar in Columbia, South Carolina, in town for the Southeastern Independent Booksellers Association annual conference. It was the fall of 1999. My pal Tom Franklin had mentioned his name to me, said I’d want to get in line on Sunday morning for a signed copy of his chapbook.

“I’ve never heard of this guy,” I said. “Is this something he self-published?”

“No. But it’s independently published by a woman who lives in his hometown,” Tom said. “It’s one short story, in a limited run of 250 copies. All of them numbered.” I had a bookstore back in Fairhope, Alabama: Over the Transom Used and Rare Books. Tom had heard my story about selling one book for more than $6,000 to a collector. “Trust me,” he said, “you haven’t heard of William Gay but that’s about to change when his first novel comes out in November. And you do want to have one of these chapbooks.”

The bar was crowded, people standing up, brushing past, and Tom turned to greet a man. “Hey William,” he said. “I was just telling Sonny about you,” and clapped me on the shoulder.

I don’t know what I was expecting. First-time author, maybe a young college type. No, this writer had some miles on him. Older than me, I guessed. And with long hair, kind of curly. I couldn’t see his eyes. But something about him drew me in.

“Hey, Sonny.” His slow Tennessee voice was musical and had a kind of smile in it. He was wearing jeans and a rumpled black velvet-looking sport coat with broad lapels. Out of fashion.

Never would William run off with a better offer to some livelier place when I was content to be that older guy and keep it low-key.Pretty quick I found myself sitting in a booth with the man. Just the two of us. And we fell into an easy conversation about editors. William’s heavy drawl was the real version of the fake thing that actors foist on moviegoers in hillbilly movies. It belied his mercurial intelligence and an English professor’s vocabulary. I asked him what he did besides writing. “I’ve hung some sheetrock,” he said. His wit shone a light you could read by in a dark corner. I decided I liked this guy a lot.

And like two men shooting pool, we took turns across the table. Him then me. Me then him. Ratchet-jawing like drunken sailors on leave in Barcelona, Spain. A pattern we’d follow in the years to come that would distract us in the car and make us miss our turns. Like overshooting a ten-acre clean, well-lighted interstate exchange, I-95 south off I-10 eastbound, that we didn’t catch until we saw the Atlantic Ocean in Jacksonville. I asked how in the hell did we do that? William did not like to drive, didn’t like to merge or go over bridges, and I had the wheel on all our road trips. William said, in matter-of-fact monotone, “I reckon we were talking.”

But our talking was not triflng gossip. It was on our New England trip that William explained to me why Robert Penn Warren’s “Blackberry Winter” was a perfect short story. Said if you removed or added just one word from it, you’d damage it.

Same ride I quoted by heart to him a paragraph from his The Long Home:

Morning. A hot August sun was smoking up over a wavering treeline. Such drunks as were still about struggled up beneath the malign heat slowly as if they moved in altered time or through an atmosphere thickening to amber. The glade was absolutely breezeless and the threat of the sun imminent and horrific. The sweep of the sun lengthened. Windowpanes were lacquered with refracted fire. Sumac fronds hung wilted and benumbed as the whores and smellsmocks rose bedewed from the foxglove and nightshade. Strange creatures, averse or unused to so maledictive a sun, they were heir to a curious fragility, as if left to the depredations of the sun, their very flesh would sear and blacken, their limbs cringe and draw like those of scorched spiders.

Then I asked him how long it took him to compose those lines that scattered my mind and squeezed my chest. “Oh, however long it took me to set it down,” William answered. I called bullshit. And he said, “No. I hung drywall by day when I wrote that book, and I composed whole pages in my head while hanging boards.” Then he confessed that he had a photographic memory for words on pages. Even from other writers’ books. I drove in silence for a mile or two. Considering this man in the passenger seat.

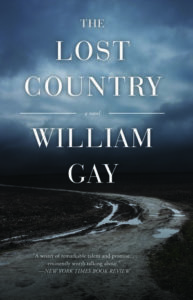

When, short weeks after he died, I read the handwritten manuscript of The Lost Country, what pages had been found by then, and I came across the paragraph that included the book’s title, that time, too, my heart stumbled and I cried for the loss of my friend.

On one of our trips the bed and breakfast the college had lined up for us was, well, dainty, and heavy on the pastels. William went into his room and came right back out again. Didn’t even put down his bag. “Can we go to a motel? I’m afraid I’ll be swarmed and smothered in my sleep by butterflies.” We left. Found a handy motel where I thought up some story for our hosts.

We couldn’t blame our wrong turns on whisky. I never once saw William Gay drunk, co-piloting or not.

But he and I did belly up to a bar now and again. Like the night in Nashville we were parked on stools when three young women came to stand right beside us. They ordered drinks and scanned the room, blessing the barroom’s ambience with their centerfold looks. When they left in a swirl and sway, 15 minutes later after one round of cocktails, I said, “Did you see that? I mean, those girls were clearly looking for somebody to play with and they did not even glance obliquely in our direction!”

William didn’t look up from his beer when he said, “I guess you ain’t checked your expiration date lately, have you?”

Another night, this time on Beale Street in Memphis, it was obvious how poorly we two fit into the scene when William said to me, “I’m ready to go anytime you are. This looks like a damned dress rehearsal for the bottom level of hell.”

William would always hang with me when we were out in some town. Never would he run off with a better offer to some livelier place when I was content to be that older guy and keep it low-key. He and I and Suzanne Kingsbury sat at a table together in the afternoon’s late sun in Jekyll Island, Georgia, during a weekend’s literary conference, and his editor came up to our table. She told William, “The car is here. It’s time to go.”

William said to me, “Come on, Sonny, let’s go.”

“Your friend can’t come with us,” the editor said. She did not look at me.

“We came together,” William said.

“I’m sorry,” she said. She told William it was, of course, okay for him to bring the lady. There were people expecting him, she said, and they really should get going. William settled back in his chair and told his editor he was not going, and took up the conversation where we’d left off. He didn’t speak further to her. Neither did he look at her. Neither did he go.

I think most men would have apologized and taken the ride with the cool people to the cool place. After all, William was expected. But William Gay was not most men, nor like them in most ways. I once asked him did he ever feel like he was an alien when he found himself a stranger amongst people and their peculiar ways, their manner of living and speaking and behaving. “No,” he told me. “I feel more like I have been set among aliens.”

He was right at home in his skin, and didn’t need to fix up different when company came calling, nor duck when he was caught out. When I came calling to his cabin in Hohenwald, he’d always ask me what I wanted to eat, and he’d have it homemade on the stove when I got there. He’d have clean sheets on his bed, all made up for me to sleep in, and wouldn’t have it any other way. He’d take the couch. His dog would keep him company.

I once pushed my publisher to let me include, late in the production cycle, one more author’s work in Stories from the Blue Moon Café. The guy, a good writer, had been on a dry spell of late and needed a break. And then that writer withdrew his story. Just days from going to press. He’d got a more prestigious offer from an iconic literary magazine, and told me he was sorry, but, quite frankly, he needed Southern Review more than he needed our anthology.

I was pissed off, and called Tom Franklin to bitch and vent. Tom stopped me. “Well, Sonny—you and me—we both know only one writer who wouldn’t have pulled their story, and, sorry, but I’m including us both in that count.”

“William Gay,” I said.

“William Gay,” he said.

He was a superior man. Willing to sell his literary papers to help with someone else’s doctor bills. Or to offer me a loan when I lost my home to a foreclosure sale on the courthouse steps in 2008.

On one of our highway runs, we made a little detour and stopped at my mother’s house in rural Alabama. My brother Frankie lived with her and took care of her and wanted to meet William Gay. When we went inside, my mother was upset because Frankie had failed for four days, he admitted, to figure out what she wanted from him. Mama couldn’t speak since a stroke 15 years earlier, and could only gesture and say, “Okay, yes,” or “Okay, no.” I gave it a try, sat on the sofa with her while The Price Is Right blinked on the TV.

My brother Frankie leaned over to me and said, “I like this man. Sort of figured I might. Just a feeling I had, you know?”Mama gestured in a direction that could have indicated the hallway to her bedroom, or the bathroom, or something outside in the unknown distance. William walked into the living room to stand near my mother. He was interested in her trouble. When I shifted my Is it bigger than a breadbox? approach to nearby towns in the general direction of her pointing, she lit up when I said Vernon.

“Okay, yes!” she said, and even gave a little laugh, relieved for some progress finally. Frankie looked on. William watched and listened. Mother even motioned to William, as if, Please, help my dimwit sons!

“Let’s see,” I said. Then, to add a bit of levity, and keep the mood going, I asked, “You want to go to the jailhouse in Vernon?” But my comedy was weak and my mother’s face conveyed to me a deep frustration that quickly devolved into sadness. I thought she was going to cry. I got serious. “Do you want to go and visit Uncle Carl there?”

“Okay, no.” And then her lip started to tremble and she looked down the couch and out the window. She was afraid. There was no humor at all in connecting her very sharp mind to a broken voice.

“Is Vernon the county seat?” William asked.

“Yes,” Frankie answered, “same pissant courthouse on the same pissant town square as all the other county seats in this pissant state.” My brother did not like government.

“Have y’all paid her land taxes? I just paid mine a while back.”

Then my mother did cry out, “Okay, yes, yes, yes!” And wept and held out her hand to William, who took it. William sat down on the other side of her and settled in to looking at The Price Is Right on the television screen. Like there was nothing else that mattered in this world. My mother patted him on the knee and cut a smile now and then at me and her other son.

When William and I headed out later, my brother Frankie leaned over to me and said, “I like this man. Sort of figured I might. Just a feeling I had, you know?”

I do know. It’s what happens sometimes when you meet a good man.

That chapbook? The one by the writer I’d never heard of? I sat in the back seat of my Ford Explorer and read it aloud to two other men, Kyle Jennings and Frank Turner Hollon. We were southbound back home, toward Alabama. A story called “The Paperhanger, the Doctor’s Wife, and the Child Who Went into the Abstract.” When I finished, the vehicle had slowed from 75 to 50. Somebody finally said, Damn!

And I said, “I gotta get this guy down to read in my bookstore. But I heard he doesn’t drive.”

“Sounds like a road trip,” Kyle said.

Yes, and what a road trip it was. Here and there, over and over, again and again. Until one day almost six years ago I got the news, behind the wheel, on my way to pick up William and go to a reading at Lincoln Memorial University, that my traveling buddy had died. But, because he wrote books, and because this manuscript was finally found, the road trip continues.

__________________________________

From the foreword to The Lost Country by William Gay. Used with the permission of the publisher, Dzanc Books. Foreword copyright © 2020 by Sonny Brewer.