Wicked Wouldn't Have Been What It Is If I Hadn't Written the Novel by Hand

Gregory Maguire on the "Word-Pictures" Revealed By Longhand

So, you ask, how am I doing? I mean in pandemic behavioral terms? Well, I’ve avoided succumbing to the syndrome that befalls some, that of morphing into a deranged über-hausfrau. I suppose this is because I’m fairly orderly to begin with. About a year ago, the novelist Ann Patchett and I tore up the cybernet with a feverish correspondence comparing her campaign not to buy anything for a year with mine, which was to throw out three things a day for 365 days.

We agreed that we have a similar horror of baggage—that stuff we travel with that the Romans, I’m told, called “impedimenta.” But Ann and I seem to go about subduing our demons with different strategies.

Is there a relationship between an aversion to material goods and a compulsion to make fictions? Our ruminations were inconclusive on the matter, though I think we conceded that storytelling existed, for some, to use up ideas with which we are burdened. Storytelling would make us free if we could park our obsessions on the page rather than carting them around with us in the wrinkles in our foreheads.

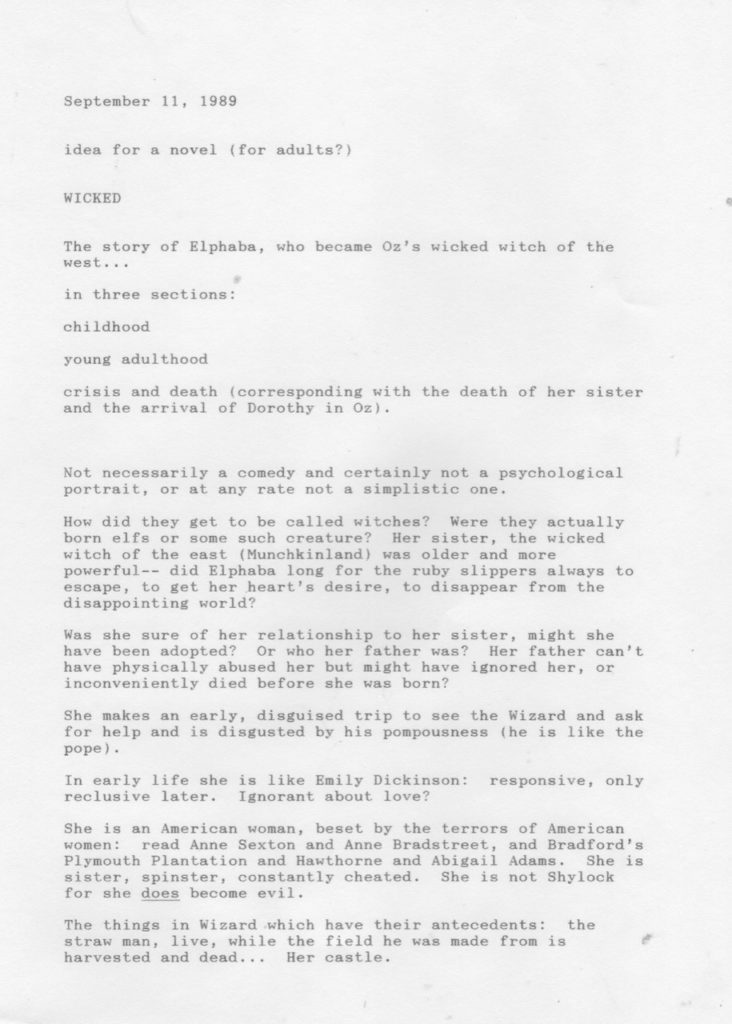

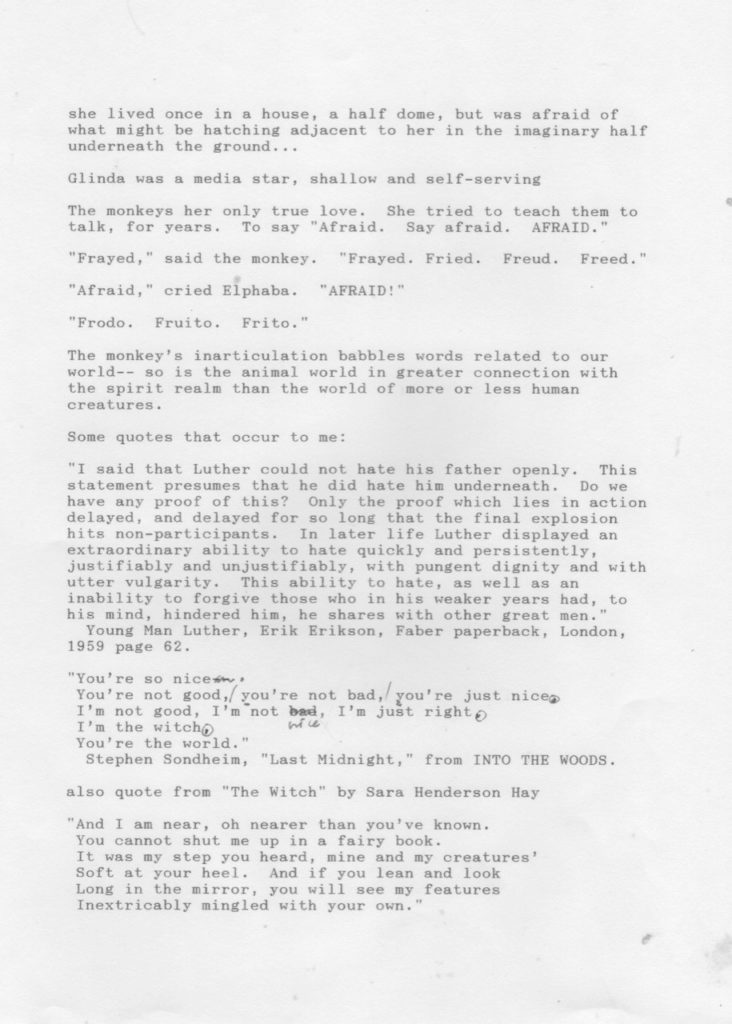

My orderliness being a given, then, I was surprised recently when an old folder turned up in a file drawer reserved for tax documents. In it, I found a few pages that appear to be my earliest notes on the novel that would become Wicked, and a page or two of handwritten first-draft effort.

These three or four pages—the initial handwritten prose effort and my “idea page”—notes printed in dot-matrix technology, that’s how old they are!— predate by several years the 1992 document that I donated to the archives of the library of the State University of New York at Albany. I had fully forgotten that in 1989 I’d already come up with the book’s title and begun to scratch out an opening scene.

So the pandemic has encouraged archeological findings that might otherwise have been lost forever; one can say at least that much for the disaster, if nothing else.

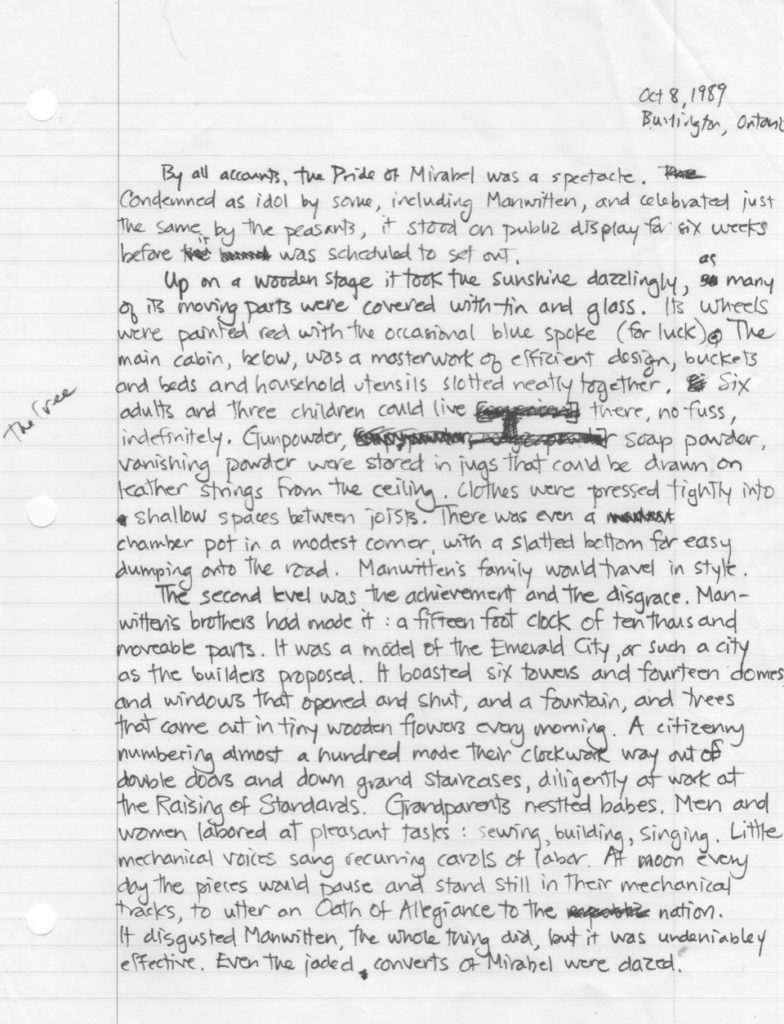

What you see here is a description of what became known, in the novel’s final draft, as the Clock of the Time Dragon. Its mechanical counterpart on Broadway is named Oswald, masterwork by Eugene Lee, the Tony-winning set designer of the musical show Wicked. Oswald has leered above the proscenium on all five continents where, to date, the musical has played, the menacing scrap of clockwork drollery flashing its red eyes and blowing smoke out of its tin-plated nostrils.

To write a beautiful and captivating word—let’s say, oh, why not, “Oz”—is first to master the art of drawing a circle.

Hardly a scrap of language from my initial feint appears in the published novel. Indeed, likely I’d misplaced these pages by the time I began a more certain draft three years later in a spiral-bound college notebook (housed at SUNY’s Univ. of Albany). Those hand-written opening lines deliver almost verbatim the prose that launches chapter one of Wicked, which appeared 25 years ago this season.

What intrigues me about these pages, though, is the way that my writing fiction in my adult life resembles how I wrote stories when I was 8 or 9. By which I don’t mean the kind of story I was telling. No, I mean that the act of telling a story that involves Coleridge’s famous “suspension of disbelief”—a wild fantasy about chicanery, magic, other-worldliness—is accomplished by a handwritten effort of precision and legibility.

It seems to my eyes now as if this passage you see here was put down by a person used to tallying columns in an accountant’s ledger. Creative and fecund disorder regulated by an orderly hand.

*

The act of writing by hand does several things for a writer. For one thing, for a child to be able to write a single word at all requires first to be able to draw the letters. Drawing is at the core of language, no less so than breathing is at the core of singing. To write a beautiful and captivating word—let’s say, oh, why not, “Oz”—is first to master the art of drawing a circle.

No small achievement for a young person with limited fine-motor skills. Then consider the complicated “z” that follows, the antithesis of the “O”—lower case instead of upper, full of angles and reverses and arrests instead of a perfect consistency of line.

I began to write books by loving to make pages. Loving to spell words. To draw. Doing a picture of a cowboy and a cat seemed, in early days, to rely on the same skill set as being able to cross the “t” in “cat” and to remember which way the “b” goes in “cowboy.” (A “cowdoy” was, among other things, a bad drawing.) As the years of early grade school passed, my handwritten words learned to march with metered confidence across a sheet of blue-ruled school-paper. This gave me nearly the same pleasure as doing a good drawing of a cowboy. Or a cat.

Of course the act of writing with the art of drawing. The aim of storytelling is to make convincing pictures. The author has to give the reader something to see. To call it a word-picture may sound juvenile, but that circumlocution returns us to our pre-literate days of oral storytelling. (Those cave paintings in Lascaux may well have been the first graphic novel.)

Long before I heard of left brain-right brain theories of cognitive function, before I was an abstract thinker at all or capable of speaking my thoughts, I knew that drawing and writing inform each other. When I was a child—a diligent and even monomaniacal writer of stories—if I hit a writer’s block in my prose, I would simply draw an illustration in the corner of the page and see what it showed me. Often a cue to the next written turn of events was supplied by what my visual mind wanted to draw.

*

I still begin a new novel by hand. Writing by hand, among other things, is onerous and painful. One has to go slowly, to hesitate. The wrist aches. The mind freezes. Pausing to shake the crimps out of the muscles buys the writer a few extra moments to consider the best way to sidle into the next sentence, lasso the next image.

L. Mencken is reported to have said about some forgotten book, in words close to these, “This book sounds as if it was written on a typewriter by a typewriter.” He may have been speaking of a “typewriter” as an underpaid office clerk rather than as a machine, but we know what he means.

We look at the great dragon-clock of our own invention, and wait for its parts to move, to take on life.

The fluidity available to the expert typist on a keyboard comes at a cost. When words arrive in too much of a rush, they can be ill-considered. They can sound commercial. They can trade product (the precious daily word count) for precision (but have I said what I truly need to say at this point in my narrative?).

*

In the page you see reprinted here, the prose picture mirrors what I also love about drawing. Parallelisms, surprises, concrete details both convincing and arresting. What fun I was having—I’m sure of it.

The subject of this page, which would become the Clock of the Time Dragon, or Oswald Over Broadway, is here called the Pride of Mirabel. This is a traveling clock loosely inspired, I bet, on the famous Männleinlaufen mechanical clock in the Frauenkirche in Nuremberg—I have a postcard of that clockface somewhere in my files. Oz’s ominous and omnipotent dragon-clock is likely also inspired by the 1964-65 New York City World’s Fair exhibit, Disney’s “It’s a Small World,” which I first saw in Flushing, NY, the year I turned ten. Mechanical magic.

I note in the second paragraph my use of materials (“tin and glass”), and colors (“red with the occasional blue”), as well as verbal patterning: “Gunpowder, soap powder, vanishing powder…” Note how the hint of magic, or at least of sleight-of-hand, is salted in as the third in the series after more household items. Tricksy! Immediately in the next paragraph, I up the stakes, laying in the dynamite of moral conflict we require in any story worth pursuing. “The second level was the achievement and the disgrace.”

Mind, I don’t claim any merit in this passage. Were I a more cautious person, I wouldn’t want anyone to see such an early draft. This page does make my point, though. All of the Oz I came to reveal in the four-volume series known as The Wicked Years grew out of looking at something physical in my mind, and then drawing it in my own hand, by heart.

To be able to imagine something well enough to describe it is the beginning of knowing it by heart, I think. Saint Paul says that now we only see through a glass darkly, and that in maturity we come to put away the things of a child. But the job of a child is to look through that glass darkly and try to see anyway.

In order to create, the child uses every scrap of information on hand—the intoxication of older stories—the moods of joy and sorrow that grip the human soul—the paradoxes of what is known and unknown about the secret adult land from which all children are forbidden.

We draw what we know, by hand and words, until we begin to draw what we don’t know. Then we look closely to see if we can read what we have made, to see if we can decipher these matters to which our own creative urges have proposed we pay attention. We look at the great dragon-clock of our own invention, and wait for its parts to move, to take on life. To tell us what it means. We look to interpret the magic that our own invention has taught us to draw, to spell. We spell as if it were a magic spell every word we know by heart, and each word draws a whole world close around it.

__________________________________

The 25th anniversary edition of Gregory Maguire’s Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West is available now . . .

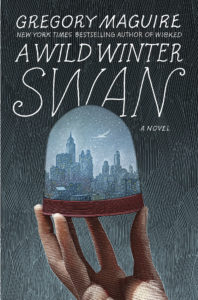

. . . as is his new novel, A Wild Winter Swan.

Gregory Maguire

Gregory Maguire is the New York Times bestselling author of Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister; Lost; Mirror Mirror; and the Wicked Years, a series that includes Wicked, Son of a Witch, A Lion Among Men, and Out of Oz. Now a beloved classic, Wicked is the basis for a blockbuster Tony Award–winning Broadway musical. Maguire has lectured on art, literature, and culture both at home and abroad. He lives with his family near Boston, Massachusetts.