Why You Shouldn’t Read Historical Fiction to Learn History

Juhea Kim on the Role of Literature in Lessons About Humanity

A few weeks ago, I went to a friend’s book club and met some new people. One of them said to me, “You should meet my wife—she’s also Asian!”

Before I go any further, let me just say I found this person funny, affable, and worthy overall. But I did cringe upon hearing this overture that countless white males have said to me throughout my life. (A popular variation is “my friend’s girlfriend is also Asian”—dropped as randomly as possible, at any point in our acquaintance.) No matter how many times I’ve heard this, it never fails to bewilder me when people outside my race fixate upon it as the primary trait by which categorize me.

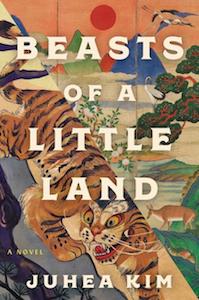

A similar bewilderment took hold of me when my novel started receiving early reviews. I was struck by how highly critics rated the educational merits of the book. Early trade reviews highlighted Beasts of a Little Land’s insights into the historical era. On Goodreads, too, readers mentioned their desire to come away from a historical novel feeling as though they’ve learned something.

On one hand, artists can’t regulate how their work is experienced (no matter how much they might wish to). It is tempting to believe that what we create always remains within our control; but this is an illusion in art, as in other aspects of life such as love and work. And there is something invaluable, maybe even essential, about the reader (or the listener, or the viewer) being the co-creator of art. In the words of Josef Albers, the abstract artist, “art is not an object, but experience.” So while there may be a specific reason someone wrote a book, there is no single correct reason for reading it. And fiction can offer rich and valid rewards of learning about a historical era and an unfamiliar culture. Historical fiction has the rare power to open our eyes to new dimensions outside our frenetic yet myopic contemporary life—to offer deeper understanding than a string of news articles and Wikipedia entries can provide.

On the other hand, I believe that the onus of writing fiction that gives history lessons falls unfairly on authors of color. People didn’t judge Lauren Groff’s Matrix or Amor Towles’s Lincoln Highway by their ability to impart knowledge about medieval France or midcentury America, for example. The former was praised as a bracingly timely read at a time when Texas has outlawed most abortions and issues of bodily autonomy have risen again to the fore. The latter’s treatment of race, class, and gender was described as making clear parallels with our own tenuous era. Although these books are also set in the past, they are primarily discussed through an artistic lens. The focus is on how their message relates to our lives today or the timeless human experience, not whether they can be instructive about history.

This generosity—the assumption that a work is worthy of being discussed for its artistic merit—is not readily extended to writers of color, even when our works are not more “alien” than those written by white authors. Most American readers know just as little about 12th-century France as about 20th-century Korea. And yet, education is less of a priority for Groff’s readers, possibly because the book concerns white characters and culture. The opposite side of this coin is that authors who write a non-white book must brace themselves for some serious othering.

Authors who write a non-white book must brace themselves for some serious othering.From the moment I started writing my book, I’ve felt burdened by making my protagonist a traditional Korean courtesan (giseng): I chose this because the giseng were the most educated, accomplished, and romantically and financially independent women in Korea for centuries, which created possibilities for more interesting characters and better plot. I knew this choice could easily get my book typecast as the unctuous Asian Historical Fiction, although the giseng in my book are not more lewd or sensational than medieval nuns, Brooklyn Navy Yard divers, or early female pilots. They are as sexual as women, across the boundaries of time and space, are. Yet Asian female characters in a historical era can pigeonhole a book into a weirdly salacious mould and label it primarily as Asian Historical Fiction rather than Literary Fiction, with profound critical and commercial consequences.

To Asian writers, the pressure to provide an educational (but also sensuous!) Asian Historical Fiction book for the Western reader is as frustrating as the invitation to meet all the Asian wives and girlfriends of white men: it’s the treatment of our books as “Asian” books and ourselves as “Asian” people, instead of just books and people. It’s also a call to behave and perform according to Western expectations and needs, and a kind of well-intentioned Orientalism.

So why read historical fiction if not to learn history? While writing and revising this novel for five years, it didn’t once occur to me to make my book educational: I was haunted, however, by the goal of making it edifying. To me, historical fiction is less history and more literature. I chose to write about early 20th-century Korea because it was a time of an all-out struggle that revealed what we are willing to live and die for; when oppression, violence, and injustice called forth the values of courage, loyalty, and compassion into stark relief. I chose this epoch because it reminded me of our present day when the stakes are, if anything, even higher. My novel is meant to be read as a story about humanity, not just about Koreans living in a distant little land some hundred years ago.

In his Nobel lecture, Alexander Solzhenitsyn said this about the role of world literature. “I believe that world literature is fully capable of helping a troubled humanity to recognize its true self in spite of what is advocated by biased individuals and parties. World literature is capable of transmitting the concentrated experience of a particular region to other lands so that we can overcome double vision and kaleidoscopic variety, so that one people can discover, accurately and concisely, the true history of another people, with all the force of recognition and the pain that comes from actual experience—and can thus be safeguarded from belated errors.”

What he emphasized is that readers should pick up one of these books not just to amass factual knowledge about another country’s history, but to identify the common threads of the human experience. And while it’s not wrong to learn history through fiction, that shouldn’t be the measure of a novel, especially if that standard applies overwhelmingly to one group of authors over another. After all, a novel’s first duty isn’t to teach you what you don’t know—but to show you what you don’t know that you already know.

__________________________________

Beasts of a Little Land is available from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2021 by Juhea Kim.