Why Send Whale Song Into Space?

On Carl Sagan, Humpback Whales, and Alien Intelligences

Remember whale song? Me neither. We are far, far away from the quiet age of sail. That’s how cetologists Roger Payne and Scott McVay dreamily describe the centuries of maritime culture prior to propellers. In their article, “Songs of Humpback Whales,” which appeared on the cover of Science magazine in August 1971, they hearken back to quiet seas, where whalers could occasionally hear the sounds of their prey through the wooden hulls of their ships. The hulls acted as amplifiers. “In this noisy century,” Payne and McVay write, referring of course to the 20th, “the widespread use of propeller ships and continuously running shipboard generators has made this a rare occurrence.”

It was Second World War research into sonar and antisubmarine warfare that made it possible to capture whale sounds underwater, by means of new technologies. Humans began to hear whales again, despite the ship noise, or, since this was a significantly different experience than hearing through a wooden hull, to hear them for the first time. In fact, for the first time in history, humans who had never even been to the seaside could hear the sounds of whales.

At the time that issue of Science appeared, most existing recordings were of odontocetes, or toothed whales, like dolphins, orcas, porpoises, belugas, and sperm whales, whose vocalizing consists primarily of clicks, squeals, squeaks, and whistles. Many of those sounds we now know to be a form of sonar called “echolocation,” in which high-frequency clicks bounce off objects, allowing whales to “see” their underwater environment in exquisite detail. The rest constitutes communication about which we still know very little.

It wasn’t until the recordings of mysticetes, or the giant baleen whales, that it seemed appropriate to refer to whale sounds as “songs.” Baleen whales do not echolocate, but instead make low-frequency sounds that serve to communicate over great distances, even passing around obstacles. The sounds happen in repeating patterns, causing researchers to group them with other song-like behavior, like that of birds. But these sounds came to be called songs not only because of structure, but also because of their particular sonic qualities. Unlike toothed whales, the baleens—like blue whales, fin whales, gray whales, right whales, and of course, the majestic humpbacks—have vocal chords. And due to the enormous distances their sounds travel in water, baleen whale songs constitute the largest communication network for any animals, with the exception of humans.

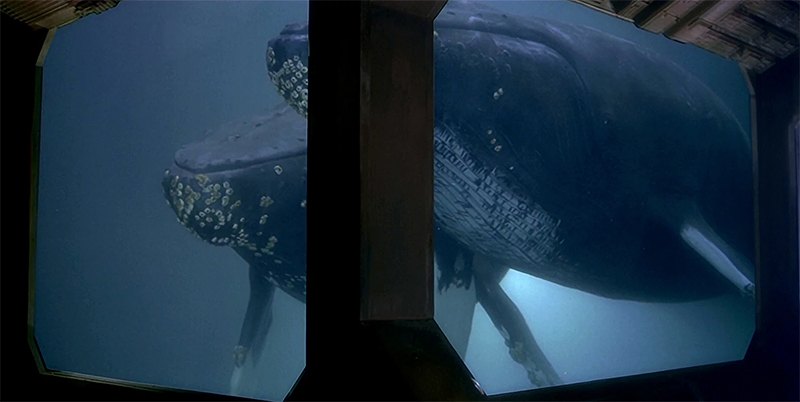

A humpback whale breaching. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

A humpback whale breaching. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

The first humpback recordings came into existence entirely by accident. In the 1950s, Frank Watlington was an engineer working for the US Navy at a top secret listening station in Bermuda, where the United States was listening for Soviet submarines. His job was to record dynamite explosions and, dropping the broadband hydrophone he had created just for this purpose to the great depth of 1,500 feet one day, Watlington happened to catch something he wasn’t prepared for. The sounds were actually in his way, the noise on his dynamite recordings.

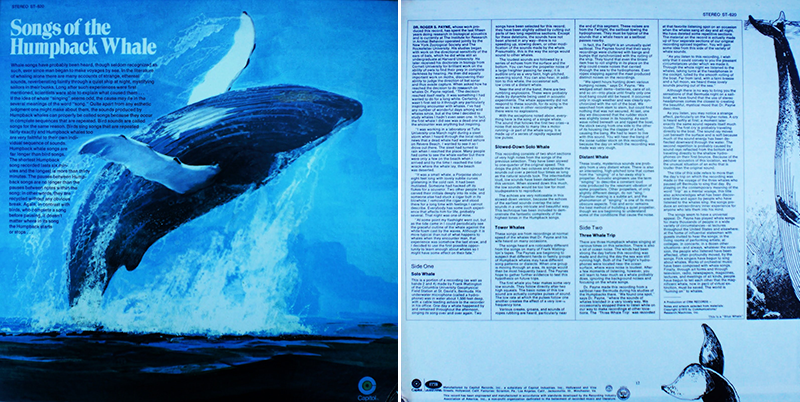

Amused and intrigued, he played them for folks at a square dancing function, who were among the first humans to hear whale sounds on playback. Watlington didn’t know what to do next, so he handed the recoding over to the young Payne and McVay, who had come to Bermuda to study the already very endangered humpbacks on their migration. It was they who “discovered” the humpbacks in the way one discovers a new vocal sensation, by means of something like a demo. Payne subsequently produced Watlington’s recordings of humpbacks, as an LP called Songs of the Humpback Whale, released in 1970.

Songs of the Humpback Whale. Photos via flickr/recordoobscura.

Songs of the Humpback Whale. Photos via flickr/recordoobscura.

Songs of the Humpback Whale became one of the most important aural documents of the modern environmental movement. It was central to the Save the Whales campaign, whose originator, Christine Stevens, appeared before the US Congress during the Marine Mammal Protection Act debates, and literally rested her case by playing the album. In Stockholm that same year, 1972, the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment resulted in the beginning of global bans on commercial whaling.

The Stockholm Conference was the first time that the United Nations declared environmental damage as a global phenomenon to be addressed collectively by nations, and the moratorium on whaling, proposed by the United States on the heels of its Marine Mammal Protection Act, was adopted by total consensus, a vote of 52-0. In 1975, Greenpeace played Songs during their first ever action at sea, during which they confronted a Soviet whaling vessel and blasted the recording over a loudspeaker. Over ten million copies of Songs were inserted into the January 1979 issue of National Geographic, making this the largest single pressing of any album of recorded music. In 1982, the International Whaling Commission instituted a global ban on all commercial whaling, which went into effect in 1986 and holds to this day.

Given how extensively the world had depended on whale bodies as raw material just decades before, with the baleens providing us the equivalent of plastic well into the second half of the 20th century, and whale oil lighting the streets of our biggest cities, the banning of whale hunting marks what political scientist Charlotte Epstein calls “one of the most dramatic cases of complete turnabout with regard to a natural resource, and a fundamental restructuring of the resource base of our economies.” Blue whales had been declared endangered decades before Greenpeace came onto the scene, but this hadn’t stopped humans from hunting them all the more committedly.

In the late 1950s killer whales in the North Atlantic were favorite targets for the US Air Force, and Time magazine printed a story which featured the following description of such an operation, in which “seventy nine bored GIs responded with enthusiasm” to the invitation to kill orcas: “First the killers [whales] were rounded up in tight formation with concentrated machine gun fire, then moved out again one by one, for the final blast which would kill them. . . . As one was wounded, the others would set upon it and tear it to pieces with their jagged teeth.” Time did not receive a single dissenting letter upon publication of this article, which makes the fact that “a little over a decade later, such actions would have been made the object of federal prosecution” indeed remarkable.

But whale song had impact well beyond the politics of killing whales. Humpback vocalizations, which Payne described as “the most evocative, most beautiful sounds made by any animal on Earth,” in a recent NPR interview, are currently hurtling through interstellar space on the Voyager Golden Record, among the most important bits of information that humans in 1977 wished to communicate to whatever alien intelligences might intercept them in the distant future. It will be 40,000 years before they make a close approach to any other planetary system. As Carl Sagan, the curator of the Golden Record’s content, meticulously explains, “Each Voyager spacecraft has a golden phonograph record in a silvery aluminum cover affixed to the outside of its central instrument bay. Instructions for playing the record, written in scientific language, are etched on the cover. A cartridge and stylus, illustrated on the cover, are tucked into the spacecraft nearby. The record is ready to play.”

The Voyager Golden Record. Photos via Wikimedia Commons.

The Voyager Golden Record. Photos via Wikimedia Commons.

The songs are included as part of the “Human and Whale Greetings” section, in which “Hello” appears in sixty human languages spoken by UN delegates, as well as one whale language, humpback. “So as to leave no hint of provincialism in the greetings from the UN delegations, we mixed these characteristically human greetings with the characteristic ‘Hellos’ of the humpback whale—another intelligent species from the planet Earth sending greetings to the stars.” Whales fill a completely different function than birds, which are part of the “Sounds of Earth” track, or Chuck Berry, who appears on the music track. They’re included as speakers, somewhere in between humans and the alien intelligences we imagined must be out there. Whaliens.

Humpback songs were so far at the front of Sagan’s thinking about Voyager that he poetically described the whole Golden Record itself as a kind of whale song: “It is, as much as the sounds of any baleen whale, a love song cast upon the vastness of the deep.” Whale song seemed to belong as much to a forgotten Earth in need of conservation, a quiet age of sail living only in the annals of human memory, as it did to Cold War technoscience, the search for extraterrestrial life, and a future in which we would be remembered by alien listeners long after we were gone. It came from elsewhere and was destined still elsewhere—haunted, distant, endangered, prehistoric, futuristic, transient, astro-nautical, exiled, extra terrestrial, a sound at the very edge of personhood, speech, music, life, habitat, “Earth,” but squarely in the sweet spot of longing.

As the Cold War drew to an end and new legislation allowed whale populations to return to more sustainable numbers, whale song began to slowly recede in the public imagination. In 1986 film Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home was still triumphantly humpback-themed. Kirk and Spock travel back in time, from 2286 to 1986, in order to save Earth from destruction by a mysterious probe emitting an indecipherable signal that has disabled the planet’s power grid and is causing massive storms. Spock determines that the probe’s signal matches the songs of humpback whales, which are long since extinct. With Kirk, he travels to 1986 San Francisco to find a pair of living whales and, in a feat of imagination and physics that seems to take the spirit of Voyager’s “Human and Whale Greetings” to something like a logical conclusion, they transport the whales forward in time to 2286. The humpbacks answer the probe’s call and save Earth and all its inhabitants from total and certain destruction.

Still from Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, dir. Leonard Nimoy (1986).

Still from Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, dir. Leonard Nimoy (1986).

Despite the happy ending, however, this film’s mournful dedication points to the impending shift in cultural climate: it was for the astronauts who had died in the Challenger disaster just months before the film’s release, a disaster that marked the beginning of the end of NASA’s space shuttle program. Meanwhile, NGOs like Greenpeace became serious interlocutors in international environmental politics rather than anti-government radicals. Gradually, whale song went the way of crystals, incense, and new age music dripping with synth and reverb. To quote David Rothenberg, a philosopher and musician who records himself improvising along with humpbacks he hears in real time through a hydrophone, today whale song is shelved with “past lives, weekend shamans, suburban yogis, and other fragments of our yearning for deeper meaning. All of this is easier to dismiss as woo woo than to take seriously.” Remember whale song? Me neither.

And yet, as Epstein provocatively suggests, the anti-whaling movement and the subsequent growth of a culture of caring about whales was never just about the welfare of whales. The passion for whales, along with its twin passion, the one for alien intelligences, had everything to do with how people imagined life on Earth and a future of different, better social relations. Whale welfare spread like wildfire because we understood, on some level, that human welfare was at stake.

The first humpback whale recordings thus serve as a strange and delicate document, not only of the songs themselves, but also of a particular moment in human culture. The dramatic shift in attitude to the whale-loving one we now take for granted resulted from changes not in how humans think about whales but in how they think about each other. And at the center of this shift was the question of communication.

__________________________________

From Whale Song. Used with permission of Bloomsbury. Copyright 2017 by Margret Grebowicz.

Margret Grebowicz

Margret Grebowicz is the author of Mountains and Desire, Whale Song, The National Park to Come, and Why Internet Porn Matters, and co-author of Beyond the Cyborg: Adventures with Donna Haraway. She has worked as a professional jazz vocalist in New York City and a philosophy professor at a number of universities.