Waiting for the Popemobile

In the same year that a rumor spread through Hektary that the Pope would drive past our village, my father took over the running of the farm and, to my grandmother’s dismay, began to introduce reforms, gradually turning our homestead into an unruly and exuberant zoo. It wasn’t just beehives and cages with goldfinches, canaries and rabbits, or a dovecote in the attic, where clumsy nestlings hatched out of delicate eggs that looked like table-tennis balls. In the middle of February, right after my birthday, wanting to cheer me up after the loss of Blacky, Dad pulled out of his jacket a little soggy, squeaking ball of fluff, which by the warmth of the stove gradually began to turn into a several-weeks-old Tatra sheepdog. We called him Bear.

That spring, my father got hold of an excavator and widened the pond behind our house, close to the road. My mother forbade me from going anywhere near it, but after she left for work I would sneak out to what now looked like a trapezium-shaped clay-pit pool. I would crouch by the mound of excavated soil, holding on to the stubs of whitewashed trees or clumps of sweet flag surrounded by frogspawn, and I would watch the wrinkles made on the water by pond skaters.

One Sunday just before the arrival of the Pope, my father handed me the binoculars and told me to watch the nearby field. “A good opportunity came up, so I got you a number in exchange for a liter of vodka,” he whispered, pointing at the farthest meadow, sprinkled with dandelions. “That’s where we’ll build a new house.”

I didn’t know what this “getting a number” involved, but I had come to think that since his return from military detention, Dad had been living in two houses: one was a stone ruin wobbling unsteadily over its limestone foundations, while the other, which for years had been forming in his head, was a clean brick house with central heating, an attic scented with resin and a shiny bathroom tiled from floor to ceiling.

That evening, I noticed that my grandmother had prepared a cake and had washed the floor with diluted vinegar, which usually heralded the imminent arrival of guests. Sure enough, shortly afterwards, women from the village began to arrive: my grandmother’s two sisters, Zofia and Salomea, almost all of our female neighbors from Hektary and, to my surprise, Stasikowa the dressmaker, who seldom dropped in on anyone because she was buried up to her ears in work. Including Mum, there were probably a dozen women at our house. They had all brought cloth pouches and farm sieves, which were covered with kerchiefs.

I thought this might be some sort of feathering evening, even though nobody in Hektary ever got together to tear up feathers in June. Instead of feathers, the women started to toss out of their sieves various scraps of colorful fabrics, fragments of dresses, housecoats, christening shawls, curtains, embroidered wall hangings, and fringes left over from Easter Turk costumes, whatever they happened to have at home, and under Stasikowa’s direction they set about sewing pennants for bunting to adorn the roadside during Pope John Paul II’s visit to Poland.

When the line of bunting was nearly ready, snaking around two rooms, the hallway and the porch, my grandmother started to lay out refreshments on the dresser and the windowsills, while Mum took out a bottle wrapped in a rag from a secret cranny in the kitchen.

“Well, girls, shall we drink to the Holy Father’s health?” she proposed. She didn’t have to say it twice. The women set aside their thimbles, rags and thread, made themselves comfortable and, sipping the homemade egg liqueur, began to spin their tales.

“Since my old man died, I can’t be bothered to melt caramel to wax the hair over my lip,” confessed the dressmaker in her low voice, hemming the last edge of a pennant. “I don’t scrub my heels with ash, I don’t rinse my hair with chamomile tea, I don’t dream at dawn about falling from a ladder. My nose has grown longer, my breasts have sagged—in other words, girls, I’m on the way out.” She laughed hoarsely.

“Oh, come on now, you want to leave us behind? Who else would help us when we need it? Who would do our sewing for weddings and First Communions? You’ve managed so long without a man, surely you can bear being alone in this world a while longer,” said my grandmother.

“And how’s little Wiola?” my grandmother’s elder sister, Salomea, asked her. “Has Aunt Flo come to visit her yet? You know, her aunt from America… her blood relation…”

“How would I know?”

The women looked at me searchingly, and I blushed all the way to the tips of my ears, because even though I didn’t understand a thing from all this mysterious talk about an aunt from America, I intuitively felt that something important was at stake. I moved Bear off my knees, and as he played with scraps of cloth under the table I pondered what blood relation could possibly come to visit me. Maybe they were talking about my grandfather’s paternal uncle’s wife, who had stashed tsarist rubles in her stockings and fled to Canada during a dysentery epidemic. But she would have had to be about a hundred and twenty.

“Keep on sewing, girls, keep on sewing, ’cause you’re chinwagging and dawdling, and the boys will be here in no time to get the bunting,” said my grandmother’s other sister, Zofia, coming to my rescue.

Someone knocked on the door, and there was a commotion on the porch. Three men stuffed the line of bunting into a jute sack and went to hang it up by the side of the road. Later it turned out that the men whose task it was to destroy the decorations had already been waiting for them on the far side of the crossing.

In the morning, I rushed to the road with Bear to welcome the Pope, carrying a paper pennant with the Vatican’s coat of arms which I had bought at the corner shop. All that was left of the half-mile of bunting were muddy shreds soaking in the ditch next to empty vodka bottles and cigarette ends. I waited for the Popemobile for several hours. It kept drizzling. Bear started to look the way he did the day Dad brought him home. The asphalt glistened like the skin of an eggplant. A delayed coach plastered with images of the Holy Father drove past from the direction of Katowice carrying pilgrims to the Jasna Góra Monastery in Częstochowa, then the blue-and-white uniforms of the junior cycle club from Poraj flashed before my eyes, then came Gienek the Combine Driver, who usually headed to the Jupiter Inn around that time for lunch, and two tractors and a lorry with the words, “Buy your clothes at CDT.” When the rain settled in for good, I took shelter with Bear under the lean-to roof of the inn, inhaling the aroma of cabbage rolls and hunter’s stew, and the buffet lady told me to go home for lunch because they said on television that the Pope had flown that morning to Częstochowa in a helicopter.

Whitsunday

In May 1984, I set out for church carrying a bundle of sweet flag, which I had picked that morning by the pond and adorned with ribbons. Water dripped from the bouquet onto my Sunday shoes. The church was filled with the smell of sweet flag leaves and silt, like a drying bog. My head started to spin. When the parish priest began to read a passage about the Descent of the Holy Spirit, the boat-shaped pulpit sailed off with him into the unknown. I slid from the bench down to the floor. They carried me outside. A woman drew a cross on my forehead with her spit.

“We must tie a red ribbon in her hair and break the spell,” she said, turning to the gawkers.

A few days later, my mother made an appointment for a private consultation with Dr. Kwiecień. The sixty-year-old physician had the kindly face of Willy from Maya

the Bee, but I saw through him right away, glowering at his clean-shaven, purplish cheeks. This weasel told my mother to wait in the hallway, where a large rubber plant stood next to a shelf, and led me to the consulting room, behind a privacy screen. He wiped the earpieces of his stethoscope on his white coat and came up so close to me that I could smell his perfume. He undid his fly, moved even closer and put his penis in my hand, like a roll of modeling clay. I jumped back and kicked his leg as hard as I could. The squeal of a slaughtered piglet must have been heard throughout the entire building. Alarmed, my mother came into the room. Kwiecień did up his fly and peeped out from behind the screen. A moment later, he sat down at his desk and started grumbling that I was a spoiled brat, since I had kicked his shin for no reason when he tried to examine my lymph nodes. He showed the red mark to my mother. Then suddenly he turned mild as an angel and declared that I seemed healthy but that I might be anemic, which would explain my excessive irritability and fainting spells. He handed my mother a blood-test form.

“After you pick up the results, please come back to see me with your daughter.”

We were walking home. The afternoon sun was shining through the branches of the birch trees growing by the road, rubber-stamping the cream-colored boughs with purple marks. My mother was silent for a long time. When we reached Boży Stok, she broke off a withy and shoved it right under my nose.

“You see this? If you kick anyone again, I’ll give you a whipping, understood?”

The following day, I came down with a high fever. I stayed home alone and lay in bed, sipping lime-flower tea. Around noon, I put an immersion heater in a metal mug, boiled some water and dipped a thermometer into the liquid. The mercury container burst. Silver beads spilled onto the bedding. I gathered them up. I hesitated for an instant, but when I remembered Kwiecień’s face, I swallowed the balls like caplets and fell asleep. I woke up a few hours later with my head swimming. I vomited as if I were trying to spit out my insides. In the end, I confessed to my parents, who had just come home from work, that I had swallowed mercury. My father dashed off to the village mayor’s house to call an ambulance.

The room at the children’s ward of the Lubliniec county hospital resembled a lime kiln in the Jurassic Uplands. Glaring light glided along the walls, condensed in the catheter of the IV drip and poured into the barely visible vein in my left wrist through plastic tubes. My mother’s face, red from crying, seemed ten years older in the fluorescent glow.

After a while, a skinny doctor arrived and took my mother aside. As he spoke, his Adam’s apple bobbed up and down, as if he had swallowed a frog. Pretending to be asleep, I eavesdropped on their conversation: “Elemental mercury is not dangerous… The intestines cannot absorb it… We’ll keep checking… We’ll keep checking every few hours.”

After the doctor left, my mother looked at me with reproach. I wanted to explain everything, but I didn’t get a chance. In the neighboring bed, a girl with crimson blisters around her mouth, who had swallowed some caustic potato-beetle poison, started to choke. There was a commotion. They took her away to a different ward.

The visiting hours ended at seven. Mum left a jar of homemade redcurrant juice on the bedside table and went home. A nurse disconnected the drip and turned off the light. I was alone at last. The bare walls flashed and shifted in front of my eyes like an origami fortune teller. The last of the light seeped out onto the street, wrapping poplars with copper thread and coming to a halt at the barred windows of the women’s prison across from the hospital. I pressed my hot cheek against the cool pane. The prisoners were performing a secret pantomime in their windows. The longest day of my life ended with the Scorpions’ ballad “When the Smoke is Going Down.” Klaus Meine’s voice drifted towards me from the nurse’s station until, around midnight, all went quiet.

The Dressmaker’s Secret

One evening, I could hardly wait to go to the dressmaker’s, but Mum told me to first put the homemade juice in the cool hallway and then lock the front door from the inside with the bolt. With the bolt because we never used a key, since it was always getting lost somewhere. Mum waited in the yard while I stayed inside and slid the knob along the door. The smell of rust stuck to my fingers. I went behind the hallway curtain, heavy with dirt and fly droppings, and popped through the little door into the pigsty. The chickens were dozing on their ladder. The cow was licking the stone wall. I climbed up to the spiderweb-covered window and jumped out into the icy air.

Mum gave me her hand. We decided to take the shortcut through the fields. Dusk was falling slowly. The frosty grass crunched under our boots. After a fifteen-minute march, the dressmaker’s house loomed up in the distance. I knocked a few times. Nobody answered, even though we could hear footsteps in the hallway. A cat jumped out of the dovecote, carrying a nestling in its mouth.

Mum went up to the kitchen window, knocked a few times and whispered, “Hello? Please open up, it’s us. The collection for church repairs isn’t until next week, and they won’t come checking the meters till tomorrow morning. I know because Janek let it slip.”

A moment later, the door opened. We walked through the hallway, which smelled of sour rye soup, into a bright room. Women’s suits, georgette dresses and coats edged with outdated trims and fringes dangled from a broom handle suspended under the ceiling; shrunken ladies’ jackets swung like hanged men. A Singer machine stood by the window. There was a little box of pins among the crystal on a dresser shelf, a button jar next to a rucksack on the floor and a mannequin with a cracked head in the corner of the room, draped with ribbons and starched napkins and impaled on a wooden pole like a straw Marzanna effigy drowned each year to celebrate the end of winter. Thimbles, buttons, pins, hook-and-eye clasps, press studs, appliqués, pieces of Velcro, and bits of interfacing were sticking out of a cardboard box behind the lamp.

My mother laid a bundle of fabric on the table and started untying the twine. A pink stream spilled out onto the dirty surface. The dressmaker examined the material with admiration, caressing it as if it were her departed husband’s flesh.

“Stunning… And what an even hem! You didn’t buy this in Koziegłowy, did you?”

“No, my sister brought it from Katowice. Apparently she waited in line all day to buy it. So, what do you think? Will it do?” Mum asked with a note of anxiety in her voice. “Can you make a gown for the end-of-school ball out of it?”

The dressmaker sized me up with her eyes, spread out the fabric, measured it with her forearm and said after a pause, “Only down to the knees, and that’s if I do my best.”

“To the knees? No, that won’t… What would the headmistress say? For a ball, it has to be longer. But maybe…” My mother touched her handbag. “Maybe you could manage to add some other fabric?”

“God forbid! What other fabric? You can tell at a glance that you splashed out at a Pewex shop.”

After that day, I went to the dressmaker’s regularly to have fittings. I got used to the smell of her hallway and her house. She would baste the fabric, wrap me in it like a mummy, sew a little. She did everything with great concentration. She’d add things up in her head, draw the pattern on brown paper and then, at the end, she’d sweep all the scraps of fabric from the table to the floor, make some tea, offer me cake, show off her wedding portrait, which hung over the dresser, and reminisce about her husband, Stasik. Then she’d lay out the cards and tell me my fortune, repeating the same thing every time: that I would have two children, a boy and a girl, and that foreign voyages, fame, and money awaited me, and when she’d add at the end that I would not find happiness in love, I’d come up with a pretext to leave the table. She would start watching Return to Eden, and I’d play with the cat, rummage through bags of fabric scraps, explore all the nooks and crannies pleated by light and shadows. There was only one room I was forbidden to enter. Of course, I tried to disobey several times, but unfortunately the room was always locked.

At night, I often thought about Stasikowa’s room. Sometimes I imagined it as a little chapel, except instead of a picture of a saint I would envision a golden cage with parakeets. Other times, I suspected it looked like a theater dressing room, with costumes and a dressing table. In my dreams, I would enter this room and try on wigs and colorful outfits.

Then one week, I mixed up my days because there was a difficult math test at school, and I went to see the dressmaker on a Tuesday instead of a Wednesday. To my surprise, the front door was ajar. I went inside. The cat was sleeping on a cushion. The clock was ticking on top of the dresser. In the dressmaker’s absence, I decided to peek into the forbidden room. I paused in front of the heavy door, thinking, “Open, Sesame,” then pushed it and looked inside. The room was in semi-darkness. When my eyes got used to the dim light, I saw what looked like a hunter’s study. Stuffed birds, deer antlers, and a shotgun were hanging on the walls. The dressmaker was sitting on the bed, half-naked, rocking rhythmically on top of a rag-filled dummy dressed in a man’s suit.

__________________________________

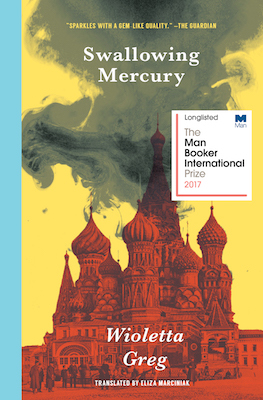

From Swallowing Mercury. Used with permission of TRANSIT BOOKS. Copyright © 2017 by Wioletta Greg (Trans. Eliza Marciniak).