Why Samuel L. Jackson Was Expelled From Morehouse College

The Iconic Actor on His Time as Politically-Conscious Student at the Acclaimed HBCU

English 353, as listed in the Morehouse College Bulletin: “ELEMENTARY PUBLIC SPEAKING. A course in the fundamentals of speech preparation and speaking.” Back at Morehouse, Samuel L. Jackson, who struggled with his stutter, thought that a public-speaking class might reduce its severity. The class helped, although not as much as an independent discovery Jackson made: he could almost always avoid stuttering by using the word “motherfucker.”

Even more important than the class itself was an offer made by the professor: a Morehouse-Spelman production of The Threepenny Opera needed more actors. Anyone in the class who joined the cast would get extra credit. Jackson couldn’t really sing, but it turned out that he “could act like I could sing.” He was cast in the supporting role of Ready-Money Matt. As soon as Jackson walked into the theater, something clicked: he knew that he had found the place he should have been all along. Soon there was a brand-new thrill: “on opening night, you get that applause. I guess it’s like a rush. Wow!”

Nobody believed that The Threepenny Opera marked the theatrical debut of a world-shaking thespian talent, not even Jackson himself. “I was horrible,” he conceded. He was aware of the contempt he inspired in the undergraduate women who formed the core of the Spelman theater program. One of those theater majors said her initial response to the sight of Jackson in rehearsal was, “What’s cheerleader boy doing on my stage?” She did concede that he had his virtues: “He was very, very fine.” Her name was LaTanya Richardson, and Jackson had noticed her too: the first time he spotted her was the tumultuous week after King was assassinated, when they were both on the same plane flight to Memphis, heading for the march with the sanitation workers. Richardson thought that Jackson looked just like Linc Hayes, the character played by Clarence Williams III in the TV show The Mod Squad: “this huge Afro, little bitty round sunglasses, and long sideburns.”

Jackson was still experimenting with different identities in different social contexts, but there was one role he wasn’t interested in: the traditional Morehouse man. “Morehouse was breeding politically correct negroes,” Jackson said. “They were creating the next Martin Luther Kings. They didn’t say that because, really, they didn’t want you to be that active politically, and they were more proud of the fact that he was a preacher than that he was a civil-rights leader. That was their trip: they was into making docile negroes.”

“SOMEBODY’S WATCHING EVERYTHING YOU DO,” said a flyer distributed on the Morehouse campus in the spring of 1969. Over the image of a clenched fist, the sheet had typed thoughts such as “Is the slogan ‘Power to Black people’ or ‘Power to some Black people…and not most’?” and “Pretty soon the rhetoric of blackness will degenerate into expositions and arguments of my mama is blacker than your mama” and “Either the tension is subsiding or the lull before the storm is here.” Most ominous was the section that read “Little House, little House, how strong are you? Somebody’s trying to huff and puff and blow the little House down. If made of sticks and straw the little House can’t stand. Little House, little House, how strong are you?” The flyer was signed, “I remain sincerely and always: God (p.s. you’d better wipe that damn silly grin off your face!!)”

In that atmosphere of threats and consciousness-raising and black comedy, Jackson joined a group of Morehouse undergraduates called Concerned Students, who wanted to petition the Morehouse board of trustees to remake the college. Their four principal demands: a Black studies program; improved community involvement with the housing projects adjacent to the Morehouse campus; people of color forming a majority of the voting members of the board of trustees; and for the six Black colleges in the Atlanta area to consolidate as one larger institution, with a focus on Black studies, to be known as Martin Luther King University.

When the Concerned Students tried to discuss their issues with the board of trustees, they were rebuffed—so they went outside Harkness Hall, the stately brick administration building where the board was meeting, and gathered up the chains that inhibited pedestrians from walking on the grass lawns. “We had read about the lock-ins on other campuses,” Jackson said. With some padlocks purchased at a local hardware store, they chained the doors to Harkness Hall shut, locking themselves in with the trustees.

The standoff lasted for 29 hours. Students painted revolutionary slogans on campus sidewalks and buildings, including “M. L. King University Now.” Some Spelman students wanted to join the protest, so they found a ladder and climbed in through a second-floor window. Those women included LaTanya Richardson: “Wherever somebody was speaking about revolution and change, I showed up for it.”

Concerned Students made sure that they fed the trustees and took care of them. About six hours into the standoff, when trustee Martin Luther King Sr. complained of chest pains, they allowed the 70-year-old to leave via that second-story ladder. “We let him out of there so we wouldn’t be accused of murder,” Jackson said.

The hostage situation ended when the trustees made various concessions (which the Morehouse administration later repudiated). Charles Merrill, the chairman of the board of trustees, signed an agreement granting the protesters amnesty, promising that they would not be punished for participating in the protest. As soon as the semester ended, however, dean of students Samuel J. Tucker, heading the Morehouse Advisory Committee, sent registered letters to various Morehouse students—including Samuel L. Jackson—summoning them back to campus for a hearing.

With some padlocks purchased at a local hardware store, they chained the doors to Harkness Hall shut, locking themselves in with the trustees.

“It has been reported to the Advisory Committee that you were among the individuals who participated in [the] lock-in,” Tucker wrote. “During the lock-in the following illegal actions were committed; forcible confinement and detention of Board members and student representatives; forcible seizure and occupation of the administration building; and unauthorized use of office supplies, unauthorized use of office telephone for long distance calls, and damage to school property.” The timing—after the student body had gone home for the summer and couldn’t protest any discipline—wasn’t an accident.

The Advisory Committee peremptorily expelled Jackson. He recalled his freshman orientation, when they had told students to look to the left and then the right, and warned them that one of the three of them would not be there the following year. “Finally I was that person who was not there the next year,” he realized.

Jackson couldn’t, or wouldn’t, go home to Chattanooga; 310 1⁄2 Lookout Street was full of disappointment and broken promises. He stayed in Atlanta, sleeping in a house rented by the SNCC, which had its national headquarters near the Morehouse campus, in a cramped second-floor office above a beauty parlor. Jackson spent his summer doing volunteer work for the SNCC at the Rap Brown Center: “We fed kids in the morning and did field trips,” he said. Leaving Morehouse had only pushed him further into political activism. “I wasn’t one of those people that was gonna walk around and get spit on and get slapped and not fight back,” Jackson said.

Jackson was spending time with Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown, each of whom served as chairman of the SNCC (succeeding John Lewis), leading the organization as it made the transition from the Freedom Riders to the Black Panthers. “I was never a Black Panther,” Jackson clarified. “But the fact that you were alive during that period in America, you had to either be part of the problem or part of the solution. We chose to be part of the solution.”

Jackson became part of what he termed “the radical faction” of SNCC. He was instrumental in a scheme to steal the credit cards of white people and then to use them to buy guns, building a stockpile of armaments for the conflict that seemed imminent: not just a race war, but young versus old, rebels versus the establishment. The stakes seemed much larger than who got to sit on the Morehouse board of trustees. “All of a sudden, I felt I had a voice,” he said. “I was somebody. I could make a difference.”

Radical conspiracies didn’t come without risk; some of Jackson’s friends died in mysterious car explosions. But Jackson’s life as a revolutionary ended abruptly on the day when his mother showed up in Atlanta and told him that she was taking him to lunch.

He got in her car, but instead she drove him to the airport. On the way, she told him that two FBI agents had knocked on the door of 310 1⁄2 Lookout Street and told her that they had her son under surveillance, and that if he didn’t get out of Atlanta, he would probably be dead within a year. She handed him a plane ticket to Los Angeles and instructed him: “Get on this plane. Do not get off. I’ll talk to you when you get to your aunt’s in LA.”

__________________________________

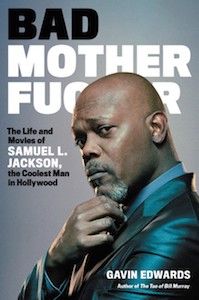

Excerpted from Bad Motherfucker: The Life and Movies of Samuel L. Jackson, the Coolest Man in Hollywood by Gavin Edwards. Copyright © 2021. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.