Why France Bizot Uses Books as the Canvas for Her Art

On Defamiliarizing What We Think of as Art Materials

Readers often refrain from marking up their books, to maintain a certain reverence for their contents and authorship. The artist France Bizot takes a disruptive approach to the book’s implicit sanctity—her work reconfirms its objecthood. It’s. . .paper. It’s not only great fiction or nonfiction, but also a mere surface as much as anything else.

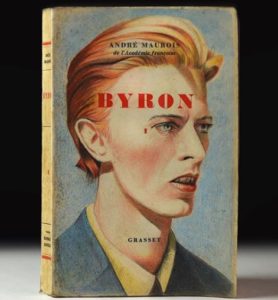

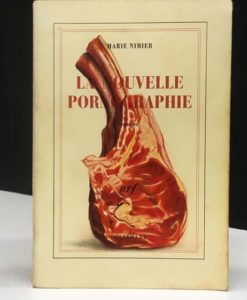

Some might balk at the idea of using a book like a sketchbook, but it’s ironically an effective way to give the medium a second wind. Bizot brings vivacity and irreverence to the sobriety of vintage French books, meddling with the monastically plain designs of a prestigious canon using Caran d’Ache colored pencils.

Minimalist covers are the signature aesthetic of highly-regarded French publishers, the abstinence of embellishment seeming to communicate a haughty intellectualism: words require no visual accompaniment! The erudite virtue of crafted sentences stand on their own!

Such covers are, of course, the most appealing to draw on.

Recently, a friend of Bizot’s was meeting with a higher-up at Éditions Gallimard who oversees its Collection Blanche—the crème de la crème of French publishing—and decided to present Bizot’s work. The rarefied imprint, founded in 1911, gets its name from its cover template, which is blank, except for an ultra-thin border in red and black. Iconic volumes of poetry, critical texts, plays, and more have been published under its aegis, from Proust to Gide, Bataille to Ionesco, Duras to Valéry.

But when Bizot’s friend returned from the meeting, it was to report that the higher-up was utterly horrified by her work. “La Collection Blanche is La Collection Blanche!” he sputtered. “It’s sacred! You cannot draw on it—you cannot touch it!” This French attitude towards its cultural institutions—eager to honor the traditions, and disinclined to rethink them—packs the drawings with an even more subversive punch.

Bizot was wildly amused by this. “I thought that was the best news!” she exclaimed, recounting the story in her ground-floor atelier in Paris’s 16th arrondissement. “You couldn’t make a scandal writing a book anymore! So if that is scandal? I’m glad.”

Bizot remains agog at the unwillingness—the overt resistance, even—that loved ones have showed over parting with their books, however dormant they lay.

Bizot mixes the spirit of an unlicensed graffiti artist with that of a pop culture obsessive. (On her pages, she has cast Mia Wallace from Pulp Fiction, Robert Mapplethorpe with whip in hand, and a fetching Sophia Loren). Moreover, she creates not only graphically impactful sketches, but sly juxtapositions that often invoke jeux de mots—wordplay—or cleverly skew original engravings.

Before she became an artist, Bizot worked for some 20 years as an art director at international advertising agencies like BBDO and Saatchi & Saatchi. Advertising conditioned her to be creative within designated parameters. “It taught me how to find an idea—how to find what you want to say. It’s really a school for concepts,” she said of the profession. “When I started, advertising was the YouTube of today.”

She buys used books in pristine condition at the specialized Marché du Livre Ancien et d’Occasion, or negotiates cast-offs from friends’ bookshelves. Bizot remains agog at the unwillingness—the overt resistance, even—that loved ones have showed over parting with their books, however dormant they lay. It’s a different kind of squeamishness than that of Monsieur-La-Collection-Blanche: it’s not about the French publishing tradition, but the sense of personal entanglement.

Reviewing her parents’ shelves, Bizot’s mother initially gave her blessing: “Of course darling, take anything you want.” But as soon as Bizot made a specific request, she was rebuffed. “Ah! Oh no, that one?! I can’t give you that one.”

Several attempts later, their negotiations had advanced no further: everything had excuses linked to memories. Even when Bizot managed to unearth a book she liked from amongst the less iconic titles, her mother remained tentative. “‘I was like, ‘I’M TAKING IT.’ What, do you think you’re gonna reread L’Étranger?” Bizot laughed. “When she dies, nobody is going to take those books. They have no value in themselves; they cost 5 euros.” She smiled. “But people love them deeply.”

The irony is that the cultural cachet of print books has languished, and the publishing industry has experienced a whiplash decline—readers use digital devices, or simply read less. “People leave books on the street!” Bizot noted. In fact, she found a clean paperback copy of Madame Bovary on the sidewalk, where someone had abandoned a pile of unwanted tomes. It just so happened Bizot was going to lunch with a friend the next day, who owns an advertising agency called Madame Bovary, and she decided to give him the book personalized with a drawing on the title page.

Rummaging through her wax paper-wrapped stacks, she explained that, more than anything, her visual choices often disclose a moment of obsession, whether it’s depicting an Instagram influencer whose dance videos she got sucked into for an entire afternoon, or a musician that has marked her since adolescence. The mood-inspired drawings are twinned with a suggestive title, whose subtext is often what drew her to the book in the first place.

The examples are varied. Her portrait of Bowie, all wonky teeth and good hair, covers a biography of Romantic English poet Byron by André Maurois. La Nouvelle Pornographie by Marie Nimier is channeled into raw lambchops, an iconography of carnivorous consumption and appetite. She paired La Condition Humaine (a 1933 novel by André Malraux) with a close-up of a flat tire, encapsulating absurdity and day-to-day defeatism. Les Puritans d’Amérique is anointed with Courbet’s “L’Origine du monde,” the pubis ensconcing a small engraving. With Avons-Nous Vécu? (Marcel Arland), the Concorde is seen going down in flames, which was “the mood of the day” for her when she found out about Brexit.

“What I’m doing here is not an illustration of the book. I don’t know what’s inside, and I don’t care,” she affirmed. “It’s the sensation of the book. I see this title, and I have this idea, and I don’t know why.”

Her images are not referencing the books’ contents—Bizot hasn’t read them. She relies, rather, on a kind of divination instead. “What I’m doing here is not an illustration of the book. I don’t know what’s inside, and I don’t care,” she affirmed. “It’s the sensation of the book,” she said of how she hones in on her book-as-canvas. “I see this title, and I have this idea, and I don’t know why.”

Books are to be read, of course—but after? They are tethered to nostalgia. They are, ultimately, totemic. Bizot’s work strips the books of interpersonal sentimentality: It doesn’t matter who they belonged to, or the “phase” the reader was in when they read it.

To her, books contain playful riddles to tease out: they are vehicles for the imagination independent of the stories they recount. “In taking this book, I can feel something about it already. Then I forget about that,” she said. “It’s just reinventing a space.”

*

An exhibition of France Bizot’s work, “Shift and Shuffle,” is on view at Gallery Backslash in Paris (June 6th–July 20th).

Sarah Moroz

Sarah Moroz is a Franco-American journalist and translator based in Paris.