Why Do We Return to the Greek Myths Again and Again?

Charlotte Higgins and Stacey Swann on the Perpetual Relevance of the Classics

Charlotte Higgins and Stacey Swann, a British classicist and a Texan novelist, have both drawn on ancient Greek mythology in their latest books—but in completely different ways. In an email conversation, they discussed their approaches.

*

Charlotte Higgins: Stacey, I loved reading Olympus, Texas, and I am bursting with questions about it. While reading your book I was reminded of what Eliot talked about in relation to myth and the novel (he was, of course, thinking of Ulysses): that myth might provide “a way of controlling, of ordering, of giving a shape and a significance to the immense panorama of futility and anarchy which is contemporary history.” I’m constantly amazed by the inventive ways novelists are using the endlessly flexible body of literature we call “the Greek myths”, and I’m eager to ask you later in this conversation about, in particular, your novel’s relationship to Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

I’m also curious, though, about what relationship you had with the story-world of classical myth before writing Olympus, Texas. For my part, there were two factors. One was a wonderful teacher at school, who taught me Latin and Greek (in the down-at-heel, rapidly de-industrializing area of the Midlands of England known as the Potteries, in the 1980s); and a particular book. The book was a retelling of Greek myths for young readers, called The Children of the Gods, by Kenneth McLeish, with beautiful illustrations by the sculptor Dame Elisabeth Frink. It fired my imagination, and, together with my teacher, set me on the path of studying classics at university. But how about you? Were classical myths part of your childhood? Was classical literature in any way part of your education?

Stacey Swann: As a person who loves Greek and Roman mythology but never officially studied it, I sometimes worry real classicists such as yourself will spy weak spots in my knowledge base. So I am both happy and relieved you enjoyed my novel, Charlotte! Like you, I first encountered the myths as a child. My mother had an old copy of Edith Hamilton’s Mythology on our bookshelves, and I was smitten by it. (So much so that when I was eleven, I did a class project on The Twelve Labors of Hercules complete with giant, multi-layered illustrations of the related constellations.)

Reading your beautiful Greek Myth: A New Retelling tapped right into those memories of sinking into a whole new universe, with its own rules and history and adherents. Though Olympus, Texas isn’t necessarily kid-friendly, I’ve had multiple readers tell me that their children helped them identify the different god and goddesses I’ve adapted into mortals. They could describe them, and their kids could suss out the inspiration. We can thank Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson series for this common expertise in young Americans, I think!

The Eliot quote you cited really resonated as it taps straight into why I’m drawn to writing fiction: narrative as a way to make sense of a chaotic and often shapeless world. On top of that, I also love the way retellings (of myths, of prior works of art, of historical events) give a scaffolding to work from. It’s one of my favorite aspects of writing, like an immense puzzle an author is working out on the page. Likewise, I so loved the organizing principle of your new book as you describe it in your introduction: “I decided to frame my Greek myths as stories told by female characters. Or to be strictly accurate, my women are not telling the stories. They have, rather, woven their tales on to elaborate textiles.” What led you to that inspired decision to use tapestries as the organizing force for the book as a whole?

CH: Percy Jackson! I have read them all, purely, you understand, as quality control before giving them to my nieces. I don’t think you should worry, Stacey, about holes in your classical knowledge: the world of mythical story in Greek and Roman literature is full of contradictions, confusions, spiraling variants on the same tale. Greek myths don’t exist in canonical forms: they are they to be retold in the moment, and exist only as contaminated, and endlessly recontaminated, versions of themselves. That makes it a realm, I think, of creative invitation rather than of austere exactitude—which is why the stories remain true and new for us, whether for the 21st-century watcher of a play by Sophocles, for example, or a new reader of Homer, or someone like you, drawing on the structures of an ancient story as the semi-hidden underpinning of their own.

The world of mythical story in Greek and Roman literature is full of contradictions, confusions, spiraling variants on the same tale.

So: tapestries. As you point out, my stories are told as if they are descriptions of elaborate textiles woven by female characters. I’m following in the footsteps of classical literature: authors from Homer to Catullus and Virgil used a technique known as ekphrasis, in which descriptions of artworks are drawn out at length, gaining their own narrative force. There’s a long poem by Catullus, for example, whose entire central central section—threatening to take over the whole poem, in fact—is a description of the coverlet on a marriage bed, decorated with scenes that tell the story of Theseus and Ariadne.

Added to that, in classical literature there are some very striking moments in which female characters take control of their story through the weaving of textiles—for example, Philomela, whose rapist cuts out her tongue, and yet who bears witness to the crime by weaving the tale of it on to a tapestry. Finally, the ideas of text and textile are closely linked in classical literature, both linguistically (as they are in English) and metaphorically.

One thing I really enjoyed about Olympus, Texas, Stacey, was the way that the huge central incident of your novel is drawn from a certain version of a classical myth, but what you do is not unlike what a Greek tragedian might do when drawing out the seed of a story from Homer—you examine it from all angles, tease out its causes, and explore its many ramifications, much more so than any single ancient text does, to my knowledge. You talk about myth giving a kind of scaffolding to your story, but I’m wondering whether you feel it gives you other things, too, beyond that structural underpinning.

I’m curious, for example, about the setting in a small town in Texas. I’ve never been to Texas, but the fact that your characters are based on the dysfunctional family of Jupiter and Juno, gave me this sense of giant characters bestriding a mythic landscape, which feels right—Texas has a mythic resonance, at least to me here in London!

SS: Knowing that Greek tragedians would take a seed from a myth and then expand and extrapolate on it with a whole new focus pleases me to no end. I remember reading Wide Sargasso Sea in college and being gob smacked by the way Jean Rhys took the mostly off-stage character of Mrs. Rochester in Jane Eyre and gave Antoinette her own novel and her own story. At yet, clearly, she was working within a very old tradition! I’ve been meaning to do a deep dive into Greek tragedy as I’ve never read many of the plays and recently a friend (writer and director Owen Egerton) told me how much inspiration he’d found in them, especially in the ways they relate to modern horror films.

It strikes me that they contain so many different genres within them—not just drama and tragedy, but horror and also, perhaps, a certain type of high-stakes, intense drama that modern readers might equate with soap operas or reality TV. (Something that has happened with my own novel, which caught me off-guard but in retrospect is totally understandable. After all, I have a brother engaged in an affair with his sister-in-law!) I wonder if these different access points add to the capacity for Greek myths to be so effectively retold centuries later?

The mythic resonance of Texas that you mentioned was indeed my initial point of inspiration with Olympus, Texas. The phrase “everything is bigger in Texas” is ubiquitous here. We think of the land itself as larger-than-life (big vistas, big skies) as well as the people. That kind of swaggering, outsized-personality seemed a wonderful fit to the swaggering, outsized gods of classic mythology. It also seemed a potent way to capture my own complicated feelings about my home state. I have an enormous love for Texas, and even that knee-jerk “Texas pride,” that surprises even me.

At the same time, I can see flaws of my state—both in history and current events—that disturb and sadden me. As an example, and to generalize a bit, the traits of “traditional” masculinity are still highly valued here: stoicism rather than emotion, strength and action over vulnerability and thoughtfulness, and violence as a way to restore honor. In my novel, I found myself grappling with the ways those traits add even more of a burden on the women adjacent to those types of men.

Your retellings, Charlotte, made me see the misogyny and oppression of women in classical mythology with a new clarity. I was particularly drawn to the Philomena chapter—not just her and her sister’s story that closes the section but also to each of the myths Philomena picks to depict on her tapestry before her own tragic events, including Narcissus and Echo, Pygmalion, and Atalanta. I’m so curious as to how this female-centered lens affected the way you explored each myth and how your choice to use that specific focus developed.

CH: It was fun imagining what each of my female narrators would weave. Homer tells us that Helen was “weaving the combats of the Greeks and the Trojans”—I radically expanded that notion, so that I have her depicting many episodes from the war, including those not so often told now, about the Amazon warrior Penthesilea and the Ethiopian fighter, Memnon. Circe tells the story of her completely terrifying niece, Medea, a witch like herself. And I have Penelope using her tapestry really to work out who she is and what she believes: she weaves the story of her cousin, Clytemnestra, who shares so many of her characteristics (resourcefulness, intelligence) but who murders her husband when he returns from the war, rather than waiting patiently and faithfully for his return.

My Philomela weaves stories of love, almost as if she’s trying them out or imagining what her future could be like, for better or worse. Her hopes are dashed––she ends up weaving another tapestry, depicting her rape, and in fact it’s the love between her and her sister that really drives the story forward to its somewhat grim conclusion.

There was a lot of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in that Philomela chapter, Stacey, and he is obviously a really important source for you too. I sense you had real fun with some of the set pieces in Olympus, Texas and I enjoyed the skilled way you worked them into the whole. I don’t think a reader would need to know that your minor character Laurel is a reworking of Daphne from Ovid’s story of Apollo and Daphne, but for someone who did recognize the source, I thought it was fabulous (and I think Ovid would have enjoyed it too––reimagining Daphne as a Houston lapdancer is just brilliant).

SS: Thank you so much, Charlotte. I think one of the many reasons Ovid’s work feels so timeless is that we all love to see the inexplicable world explained to us, at least partially. Your Greek Myths does this beautifully, too, giving us (just to name a few!) the stories of how the world was born, how humans (with Prometheus’s help) evolved, and how The Furies, with their loyalty to mothers, become Kindly Ones whose power transferred to cities. The deep level of reader satisfaction those answers create are what I hoped to achieve with the Origin stories in my own novel, scenes that show how the family wound up in such fraught circumstances.

I think one of the many reasons Ovid’s work feels so timeless is that we all love to see the inexplicable world explained to us, at least partially.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses is such a box of treasures, one that I turned to often as I was structuring my novel. And the language! One of my favorite non-writing tasks while working on the book was comparing the different translations to find the one that spoke to me the most. It’s fun to think of some future translator, not yet born, doing a future version for readers not yet born. And it’s also very satisfying to think of your book, Charlotte, sitting beside Ovid and adding more context to the lives of the women and men, the goddesses and gods within.

________________________________

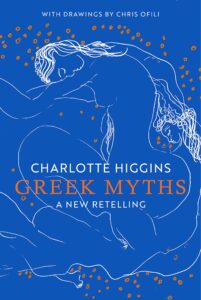

Charlotte Higgins’ Greek Myths: A New Retelling, illustrated by Chris Ofili, is available now from Pantheon Books.