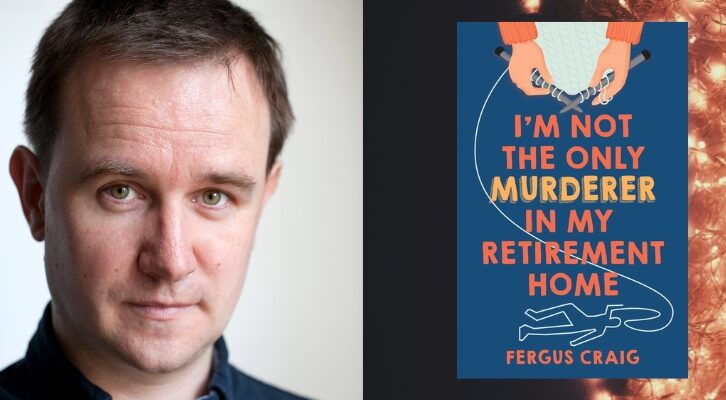

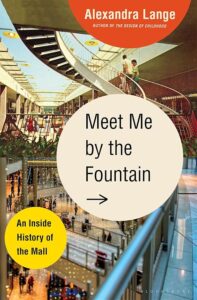

Why Do Teens Perpetually Love Shopping Malls?

In Which Clueless, Orange Julius, and Hot Topic Are Given the Analysis They Deserve

A stepped, centralized seating area appears, in one form or another, in most malls built in the 1980s. Sometimes there’s a fountain. Sometimes there are plants. Sometimes there is a sculpture. If the mall is multilevel, skylights illuminate the space from above. Escalators traveling between floors make for easy, surreptitious people-watching. Is my friend hanging out at the mall? Is my crush? This is the atrium, the most important interior space of the mall for the adolescent both architecturally and psychologically.

The earliest indoor shopping malls, with their I-shaped, bowling-alley forms, had no centralized place where groups could gather, nor much need for one. But by the early 1970s, and the advent of more complexly laid-out malls in T-, X-, or O-shapes, patrons might wander forever, missing each other in the long, low-ceilinged identical halls. Hence the atrium, which has its own storied architectural history: Ancient Roman houses were centered on open-air or skylit spaces, which provided daylight and breezes to the rooms surrounding them.

These courts often had an impluvium, or fountain, to catch rainwater from the roof, as well as furnishings for outdoor entertaining. In the shopping mall, the atrium serves a similar function, opening up the middle of a building lined with windowless shops; letting in light, water, and plants; and furnished like a living room. The atrium was the center of the social life of the Roman domus and so, too, has it been the center of mall sociability.

Gruen envisioned Southdale as an ersatz town green and, indeed, some of that civic sensibility remains in the symmetry and greenery of mall atriums. But the theatrical aspect of circumnavigating, posing, or performing in that centralized space makes this green seem more like the gossipy New England of Peyton Place than the buttoned-up town squares of earlier American depictions.

In the 2008 book Hanging Out and the Mall, consumption scholar Jennifer Smith Maguire describes teenagers perched along the second-floor railings around the atrium of the pseudonymous Mountain Mall in Ontario, Canada, grouping themselves to take advantage of the lookout at peak times after school and on Friday and Saturday evenings.

Other teens describe choosing a spot on one of the benches in the middle of the mall, where they can see the maximum number of people walking by. The teen gossips comment on the other patrons, creating an intimate bubble of gibes and put-downs within the white noise of other conversations and the mall’s Muzak.

A friend who works with Bronx teens told me that his students like to take the subway to Bryant Park in Manhattan: That open green space, surrounded by national brand-name stores, with coffee kiosks on the corners and a carousel, serves as their stand-in for a suburban mall.

The importance of the mall’s central atrium to teen life is reflected in the way teens occupy malls on film. In Clueless, director Amy Heckerling’s 1995 update of Jane Austen’s Emma, heroine Cher Horowitz (Alicia Silverstone) shares the self-delusion and queen-bee fashion sense of her 19th-century counterpart.

Where Austen’s heroine encounters strangers on the high street and in millinery shops, Heckerling’s frequents Westfield Fashion Square and Contempo Casuals. Westfield Fashion Square is a long, narrow, three-story mall, topped with a glass barrel vault and featuring indoor palms. The scene begins with Cher and Christian (Justin Walker, in the Frank Churchill role) riding up the escalators, the symmetry of their bodies reflecting that of the mall rising around them.

The movie audience is in front of them, but the mall audience is all around. Cher and Christian are mirror images of each other, self-centered and vain; she sees him as a potential love interest, but his eyes stray elsewhere—she’s too caught up in her matchmaking to realize that her ideal shopping companion might also be gay.

As they reach the top of the escalator, they are distracted by shrieks: Tai (the Harriet Smith analogue, played by Brittany Murphy) is being dangled over the mall’s glass railing by a couple of guys Cher dismisses as “generic.” Christian saves her, shoving one flannel shirt in the chest. The benign audience for the runway that the escalators provide turns more sinister.

The exposed areas of the mall are where strangers from different classes—the fashionable and the generic—come in close contact. That can provide the frisson of flirtation (finding your crush in the food court) or turn to violence (taking teasing to a threatening place). The stakes are raised by the sense of performing for an audience. Later, Cher and Tai offer up very different accounts of what happened that day at the mall, as if they’ve been watching different movies.

The interaction of teen drama and the big architecture of the mall crops up again and again in media. “In ’80s teen movies like Weird Science, the mall functions as a microcosm of society similar to a primate cage or a prison yard,” write the authors of an A.V. Club roundup of fifteen pivotal mall scenes. Smooth Talk, a darker and more reflective take on teens trying out adulthood, “is freshest and most enjoyable—when Connie and her girlfriends hang out at the mall, talking obliquely but companionably about what they’re going through, and delighting in their ability to tease and confuse their male peers. It’s a wide-open public laboratory in which they can experiment in relative safety.”

In Smith Maguire’s analysis, the mall represents the adult world. Children are taught how to navigate it by accompanying their parents (most often, their mothers) on shopping trips. It is a leap toward self-determination to go alone. “Entrance without the assistance of one’s parents is the first step” to adulthood. The A.V. Club roundup doesn’t even mention 2004’s Mean Girls, which was based on a nonfiction book by Rosalind Wiseman about teen girl behavior and includes a scene of literal primate behavior. “Being at Old Orchard Mall kind of reminded me of being at home in Africa by the watering hole, when the animals are in heat,” Cady (Lindsay Lohan) comments in a voiceover, watching coiffed teens in lowrider jeans and hoodies chirp at, groom, and pounce on one another at Old Orchard’s central fountain.

Mimi Ito, director of the Connected Learning Lab at the University of California, Irvine, and cofounder of the nonprofit Connected Camps, told me she wishes there were more digital places like the mall. “Think about kids eight to thirteen,” Ito said. “You start letting kids go to some places without adult supervision. You go to the corner store, you walk to school, you go to the mall—these are rites of passage.” But online, “once you are thirteen, you check off a box, good luck with that,” and you are treated as an adult rather than a young person who might need help navigating the world.

Adolescents try on grown-up behavior through their interactions with one another, through the clothes they buy, and through the media they consume, sometimes literally, at the mall. It comes as no surprise that, as teens shop for CDs of their favorite bands, adults also shopped for teens to put in those bands.

As long as there has been mass media, there have been teen stars, from Lana Turner, discovered at the Top Hat Malt Shop in 1937 and then shuffled into films that saw her, a pouty sixteen-year-old, flirting at cinematic soda counters, to the faux-teen stars of Happy Days, a television show set in the same nostalgic past but filmed in the 1970s.

By the 1980s, the mall was the accepted space of adolescence, with Orange Julius instead of milkshakes. To be discovered by a talent scout and adopted as a teen dream—one day you were spotted in the atrium, and the next brought back to perform there.

A 1987 Los Angeles Times article on Tiffany, the red-haired singer known for “I Think We’re Alone Now,” made the thin line between star and audience explicit.

Chances were that Tiffany Darwisch was going to do what most 15-year-olds do during the summer—go to the mall. So, when offered an expenses-paid trip to malls from coast to coast, she could not say “yes” fast enough…

“We wanted to take her to where her peer group hangs out all summer long—shopping malls,” Brad Schmidt said excitedly. “If ‘Tif [sic] is going to make it, she’s going to do it first among 12- to 18-year-olds, and what better place to expose her than in America’s playgrounds, the malls.”

In a 2012 interview looking back on her career, adult Tiffany remembered initially being booked in East Coast clubs, singing her songs, and then being stuck, unable to drink and unable to hang out afterward with the audience. Her label was thinking of dropping her, until one day Larry Solters, an executive at label MCA, was at the mall with his own daughter.

You see all these little kiosks that they set up with hair stuff and hair shows and applications of makeup and makeovers. He probably was walking by one of those and thought, “Well, what about somebody singing in the mall? This is where young girls hang out.” When they presented it to me, I thought it was great, because that’s exactly where I did hang out. My girlfriends and I, that was the safe place to be.

Every subsequent decade has repurposed the Tiffany template. Ten years later, Britney Spears’s management would send the eighteen-year-old out wearing pigtails and a plaid schoolgirl skirt, and backed by two dancers, to promote her debut album, …Baby One More Time, with a thirty-minute, L’Oréal-sponsored set performed right in the middle of a mall.

Ten years after Britney, the teen stars of the Twilight Saga, the movie adaptation of the bestselling young adult series set in a world of vampires and werewolves, were sent on a fifteen-city nationwide tour of shopping malls, supported by Hot Topic and Nordstrom.

Hot Topic, a store founded by Orv Madden in Southern California in 1989, had proved surprisingly agile in keeping up with changing teen trends. Its first location, in Montclair, sold “skulls, crucifixes, spike bracelets, pyramid belts and other hard-to-find stuff in the mall.” The next year Madden and his first employee, Cindy Levitt, added “the rock wall” lined with band T- shirts, and by 1991, Hot Topic became known as “the loudest store in the mall,” according to the official company history.

Since then, Hot Topic remained hot by absorbing fandom after fandom, punk into anime, Twin Peaks into Care Bears when rave culture picked up on nostalgia for the sweet. While urban teenagers might have been able to find studded chokers and Manic Panic, Hot Topic brought these commodified elements of rebellion closer. “People definitely associate us with 90s fashion,” Levitt told i-D in 2017. “We also represent the subversive, the anarchistic, the left of center.” The Twilight films proved a perfect fit: Glowing, sexy shapeshifters pushed parental buttons, while the young stars and PG-13 rating kept things safe, just like the mall.

A 2008 New York Times profile of dreamy vampire and Twilight star Robert Pattinson ran under the headline “The Vampire of the Mall,” and featured coverage of Pattinson’s visit to a Pennsylvania Hot Topic. David Carr wrote,

There are times when the limitations of the printed word come into focus, like when there is a need to convey how it sounded when Robert Pattinson, who stars as the vampire heartthrob Edward Cullen in the forthcoming movie “Twilight,” stepped onto a riser at the King of Prussia Mall outside Philadelphia on Thursday evening in front of more than 1,000 mostly teenage girls.

At King of Prussia Mall, it was just screaming. At other locations, fans ended up with broken bones, spilled copious tears, and asked Pattinson to bite them. Within the alternate reality of the mall, even vampires had braces.

____________________________

From Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall by Alexandra Lange. Used with permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright 2022 by Alexandra Lange.

Alexandra Lange

Alexandra Lange is an architecture critic and the author of four previous books, including The Design of Childhood. Her writing has also appeared in publications such as The New Yorker, The Atlantic, New York Magazine, the New York Times, and T Magazine, and she has been a featured writer at Design Observer, an opinion columnist at Dezeen, and the architecture critic for Curbed. She holds a PhD in twentieth-century architecture history from the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University and has taught design criticism there and at the School of Visual Arts. She lives in Brooklyn.