How the Turn-of-the-Century “Divorce Colony” of Sioux Falls Inspired a Scandalous Novel

April White on the Truths and Embellishments of The Divorce Mill

In late 1893, Mary Cahill traveled from her home in Brooklyn, New York, to Sioux Falls, South Dakota. She made the trip—like many women before her—for a divorce.

At the turn of the 20th century, the United States was a hodgepodge of state laws on divorce. Under New York’s statute, Mary had only one cause to end her marriage: adultery. She had many complaints against her husband Michael, but he had not been unfaithful. In South Dakota, which had more lenient provisions, Mary could divorce for cruelty—he called her vicious names, she said—and non-support. Over the four years of their marriage, she claimed, Michael had frittered away her $5,000 inheritance.

To fall under South Dakota’s jurisdiction, Mary would have to live in the state for six months to gain residency and continue to wait, 1,200 miles from home, as her case made its way through the courts. It was a costly undertaking—one that also came at the expense of a woman’s reputation—but so many others had made the same sacrifice that “going to Sioux Falls” had become a euphemism for “divorce” among Eastern elite.

After a long, cold winter in this small city on the American frontier, Mary found the freedom she sought. She departed soon after with her decree and—I discovered while researching my book The Divorce Colony—more than enough material to write a novel that would cement Sioux Falls’ scandalous reputation as “the city of disunited souls.”

Mary was better known to the country by her late husband’s last name. As Marie Walsh, the 50-ish-year-old woman was a successful novelist and playwright, the author of such romantic melodramas as The Wife of Two Husbands and The Romance of a Dry Goods Drummer. Now the writer turned her attention to the Sioux Falls “divorce colony,” as the cadre of unhappy spouses who flocked there were known.

In 1891, with the arrival of several prominent women, including a niece of the influential Astor family and the daughter-in-law of the Secretary of State, the city had become a flashpoint in the nation’s fiery debate over divorce, and its dramas played out on the country’s front pages. Spurred by the presence of these divorce seekers, South Dakota had already strengthened its divorce laws once, lengthening its residency requirement from three to six months. Divorce opponents believed they had closed the “divorce mill.”

Mary was herself evidence that this legislative effort to limit access to divorce was destined for failure. She had chosen to seek a divorce in Sioux Falls after the stricter law had passed. But she and the others—including Edith Wharton in Custom of the Country—who wrote books about the colony could not yet see its importance. Mary could report titillating gossip about these famous women, their broken marriages, and their new loves, but she could not tell you the story I can now. In the throes of this turn-of-the-century culture war over marriage and divorce, it was not clear that Sioux Falls would be the tipping point in attitudes toward divorce in the country.

Instead, what Mary was selling was what the country wanted: tales of “misery, sin and the follies of wives and husbands.” The Divorce Mill, published in 1895, billed itself as a book of “realistic sketches of the South Dakota divorce colony” written by Harry Hazel, a Chicago newspaper man, and S.L. Lewis, a lawyer of the same city. That “realistic” is not a synonym for “real” was widely overlooked by a reading public primed to believe any tittle-tattle from the divorce colony. (And a source of disappointment and confusion for historians.)

Newspapers panned the 25-cent book—“coarse and vulgar and wretchedly told,” the New Orleans Picayune wrote—but few questioned its authenticity or the identity of its authors. As far as I can determine, there was no lawyer by the name of S.L. Lewis practicing in Chicago at the time, and no reporter named Harry Hazel (Hazel was also the well-known pseudonym of the late Justin Jones, a writer with whom Mary would have been familiar.)

With hindsight and the power of the internet, it’s clear that Mary was the book’s informant if not its sole author. Released by the same small press that printed her other titles, The Divorce Mill is dotted with small details true Mary’s stay in the city.

While delightfully appalled Eastern papers were prepared to accept the book’s assertions as fact, the Sioux Falls Argus Leader was eager to declare them fiction. The Divorce Mill was of “no literary value” and the “workmanship shows a lack of experience and a poverty of literary education,” the paper announced. “The takes are purely imaginary for the most part.”

The truth lay somewhere in between. The Divorce Mill had captured a town divided, desirous of the money the divorce seekers brought and wary of the infamy that accompanied it. The townspeople were simultaneously appalled by the women who came in search of divorce and fascinated by them, eager to know every detail of their lives.

Some of the stories Mary told were clearly satire, most obviously the tale of the “alligator woman.” In a send-up of divorce colonists who arrived with countless trunks of fashionable gowns and bought pianos for their hotel suites to pass the time, Mary describes two young women from Philadelphia who travel with “a box containing two pet alligators instead of the usual mandolin, guitar or banjo.” The alligators, of course, escape terrorizing divorce seekers in the city’s finest hotel. Finally the frustrated, but ever polite proprietor ejects the women and their reptiles: “Ladies, your pet has caused a dreadful disturbance in this house,” he says. “I do not keep a hotel for accommodations of parties having such dangerous pets.”

The story of the woman who shot at another guest in the same hotel? That part was true, and Huldah Varker, the fictionalized version of Rita McKay, would have been immediately recognizable to the savvy turn-of-the-century reader. Rita had traveled to Sioux Falls from New York in May 1892 for a divorce from her husband Archibald, a wealthy clubman. While in Sioux Falls, she fell in love with Paul Wilkes, the son of the minister of the city’s Unitarian church. Paul’s family and church blessed their marriage, but it lasted just three years—and involved at least one duel.

The story of the divorcee whose new fiancé jumped from a moving train to avoid her was true, too. Mima Hubbard, a choir singer from New Jersey, had become involved with Clark Brown, the clerk at the local dry goods store while she waited out her “sentence,” as the residency term was sometimes called. In The Divorce Mill’s telling, “Mrs. Taylor haunted the store until the poor Thompson, who really did not contemplate matrimony, gave up his situation and endeavored to make his escape from the town without the knowledge of his fair persecutor.”

In the book and in the headlines in 1892, Clark’s cold feet and Mima’s pursuit of him were played for laughs, but now we can see it for what it is: The attempt of a young mother, abandoned and left destitute by her first husband, to take control of her life and secure a safe and stable future for herself and her son. In taking the bold step, she and the other divorce colonists, quite unintentionally, set the country down a winding path toward the acceptance and accessibility of divorce. Mary Cahill just didn’t know that part of the story yet.

______________________________

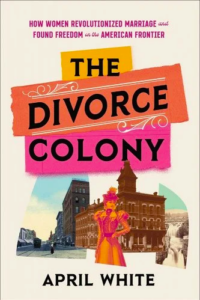

The Divorce Colony by April White is available now via Hachette.