Why Do Cats Love Bookstores?

Protecting Books and Witholding Affection for Centuries

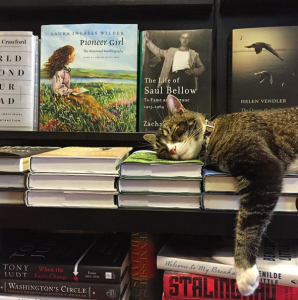

When I walk into Community Bookstore in Brooklyn, my local, the first thing I do (after saying hi to the owners) is look for the store cat, Tiny the Usurper. Tiny is the photogenic spirit of the place and gives you approximately five seconds to impress him, otherwise he goes right back to sleep on that pile of translated novels.

I understand the idea of people either being more for dogs or cats, I do. I also get the weird looks I’ve received for proudly stating that I’m for both, that I can relate to dogs and their wonderfully dumb, but fiercely loyal attitudes, as well as appreciate the way cats keep you in check by making you work for their love.

But I can say without any doubt that bookstore cats represent the apex of domesticated pets.

If a bookstore is so fortunate as to have a cat on the premises during operating hours, you can bet that feline is co-owner, manager, security, and the abiding conscience of the place. You go to a bookstore to buy a book by Ta-Nehisi Coates or the latest Kelly Link collection, but you’re really paying a tribute to the cat, whether you know it or not.

Cats generally seem above it all—that’s what I tend to like about them. Personally, I’m more like a dog, all stupid and excited about the smallest things, easy to read and always hungry. Cats, on the other hand, look right through you, force you to contemplate things; they just seem smarter than they’re letting on, as if they know everything but won’t tell. So it makes sense to see so many of them navigating the stacks of dusty old hardcovers at used bookstores, curling up next to the rainbow display of NYRB Classics. But there’s another, deeper reason cats make so much sense in bookstores—it’s in their DNA.

“One cannot help wondering what the silent critic on the hearthrug thinks of our strange conventions—the mystic Persian, whose ancestors were worshiped as gods whilst we, their masters and mistresses, groveled in caves and painted our bodies blue,” Virginia Woolf wrote in the essay “On a Faithful Friend.” As a lot of cat owners will so proudly point out, cats held a special place in Egyptian society, to the point where if you even accidentally killed a cat, you’d be sentenced to death. Cats were often adorned with jewels, fed meals that would make today’s canned food look like, well, canned cat food, and were even sometimes mummified; a grieving cat owner would often shave his own eyebrows off as an act of mourning. Even the deity representing protection, fertility, and motherhood, Bastet, could turn herself into a cat, hence the popular idea that Egyptians worshiped them. Though not exactly deities, cats did hold a very high place in Egyptian society.

Community Bookstore’s Tiny the Usurper

Community Bookstore’s Tiny the Usurper

It’s pretty obvious that cats haven’t really gotten over the sort of treatment they received in the time of the pharaoh. They carry themselves in a stately manner and demand that you treat them with a certain amount of reverence, letting you know if you’re doing a good job of petting them, when they’re ready for their meal, and making you aware of what they like and what displeases them. My cats certainly do. They love their comfy spots in the apartment, and often give me a hard time when I try to make them move, shooting me a look, letting out a sad meow, and then instigating a showdown which almost always ends with me picking them up. And those spots they love in my apartment? Among my books. And since the living room is covered in them–on shelves, my desk, piling up on the floor–my cats are never without a stack or two to rub up against, claiming the essay collections and several different paperback versions of Miss Lonelyhearts that I own.

Egypt, where cats are believed to have been first domesticated, is also where the relationship with bookstores can be traced. While mainly used to keep rodents and poisonous snakes away from homes and crops, some cats were trained specifically to keep pests from eating away at the papyrus rolls that contained texts. Without cats, in fact, it’s hard to imagine how Egyptian civilization could have so successfully weathered the diseases and famine caused by vermin—but also imagine the knowledge that might have been lost were it not for those four-legged protectors guarding the temples from tiny intruders. Over time, cats would continue to be called upon to protect sacred documents. You can find cats mentioned in Sufi tales from the Islamic Golden Age that saw huge advances in mathematics, philosophy, and physics, and European monks in the Middle Ages employed them to keep rodents away.

Today when we think of a cat chasing a mouse it’s usually in some slapstick, Tom and Jerry sort of way. The dumb cat always foiled by its tiny adversary, like we’re supposed to forgive the little jerks for gnawing on our possessions and spreading disease. It’s unfair. Especially since anyone who’s ever adopted a cat because a mice-problem knows that even if the cat doesn’t end up catching the intruders, they certainly scare them off. Cats might not always necessarily enforce the law, but they do act like security guards without guns, a living, breathing warning to mice and other rodents that it’s maybe not the best idea to overrun this place.

Herbert of King’s Books

Herbert of King’s Books

So how did they end up in bookstores? Look to Russia and a special decree issued by Empress Elizabeth in 1745 looking for “the best and biggest cats, capable of catching mice” to be sent to the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg to protect the treasures contained within from rats (this tradition lives on to the present day, with dozens of strays living in the basement of the museum). Not long after, sometime in the early 1800s, with Europeans still sure rats caused the Black Death (this idea has been mostly debunked, although now scholars believe gerbils might be to blame), and rat catchers unable to stop the rodents from overrunning filthy urban centers, governments started to pay libraries to keep cats in order to help bring down populations of book-loving vermin.

Since stores that sold books started opening up around the time of the Empress Elizabeth’s initiative (Lisbon’s Bertrand bookshop occupies the title of oldest bookstore in the world, although Moravian Book Shop also claims the title), and before the British government’s plan to get them into libraries it makes sense that shop owners would also keep the four-legged employees to keep their shops free of pests. Cats were easy to find, and all you had to do was feed them as compensation.

And once the cats were invited into bookstores, they never really left. You go to King’s Books in Tacoma and maybe lock eyes with Atticus and Herbert and then go about your shopping; you share one of the countless lists of cats sleeping next to stacks of bestsellers floating around on the web, and you take for granted that felines and bookstores go hand in hand like so many of the truly great pairings in this world. Cats are quiet and want to be left alone for the bulk of the day; they’re animals that long for solitude, much like readers and writers. It began as a working relationship, but became something more than that, something deeper. Cats ultimately became integral to the bookstore experience, a small part of why you’d rather go to your local indie than buy online or go to a chain. Sure, not every great bookstore has a cat prowling around; but in the ones that do, the cats are a big part of what makes those stores great (along with, you know, the booksellers and the comfortable places to sit and read).

Of course, if you asked a cat, he’d say he was the main attraction, but that’s what you get from a species that once reached god-like status.