Why Did It Take So Long for Star Trek to Embrace Queer Characters?

"It’s bewildering yet predictable that prior to the 21st century, Trek only used analogies to talk about queerness."

Star Trek fandom is made up of several generations, and not all of those generations communicate effectively with one another. “Star Trek Twitter” freely uses the word “Trekkie,” even though older Trekkers shame them on that one. Gatekeeping from historical know-it-alls is a problem in Trek fandom, just as much as it is with Star Wars trolls. And often, much of that gatekeeping simply comes from a “get off my lawn” mentality from older generations.

But one area the smart Trek fan generations are united in is this: It took way too long for the franchise to get its act together with LGBTQ+ representation, and even the fans who didn’t live through those years are aware of that painful truth. The outcry over Dr. Culber’s death wasn’t just about the possible perpetuation of a harmful trope; it was a collective groan from queer Trek fans who, as a community, had been waiting for healthy, happy gay characters in Star Trek since Gene Roddenberry promised they would appear.

In 1986, just after the existence of The Next Generation had been made public, fans at conventions started asking whether we’d finally see gay people in Starfleet. At a 20th-anniversary convention in Boston, a representative of a gay Star Trek fan club—the Gaylaxians—confronted Roddenberry directly about the issue. Franklin Hummel, a librarian and member of the Gaylaxians, wanted to know “if there would be a gay character on the new show.” Roddenberry gave a half-hearted promise, responding, “Sooner or later, we’ll have to address the issue. We should probably have a gay character.” Sooner turned out to be later. Much later.

Closeted for much of his early career, George Takei tells a story of Gene Roddenberry swimming toward him at a pool party in Los Angeles, during the run of The Original Series. Takei hit him up with the idea of tackling gay rights and, according to the story, Roddenberry was open to the idea but was too afraid of the series getting canceled over a “firestorm.”

“‘The times will change as we move along,’” Takei remembers Roddenberry saying. “‘But at this point, I can’t do that.’” Assuming this conversation took place when Takei remembers it happening—sometime between 1966 and 1968, it’s notable Roddenberry was talking about this kind of representation at all. Then again, any straight man working in the arts—like Roddenberry—would find himself working alongside gay people.

In fact, the man who designed the costumes for Star Trek, William Ware Theiss, was gay. That said, we don’t really need to pat Roddenberry on the back here too much. Despite what he said to Takei, putting a gay character in TOS at all was almost certainly never on the table. But the fact that George Takei even had this chat with Roddenberry in the 1960s is saying something.

We tend to give Star Trek a lot of credit for pushing racial boundaries on TV, but the truth is, the Civil Rights movement was a very public, massive social movement happening while the show was being produced. The NAACP existed in the 1960s. GLAAD did not. And just to put it in perspective, the Stonewall riots happened on June 28, 1969, three weeks after Star Trek aired “Turnabout Intruder,” its final episode. So, again, assuming this story from Takei is legit, Takei pushing Roddenberry into a “gay rights” story line was a hundred times edgier than any of the other boundaries Trek broke during TOS.

Roddenberry may have been a risk-taker when it came to race issues on TV, but in the 60s, he was also participating in a movement that was fashionable for white liberals to support. This doesn’t detract from the accomplishments of The Original Series, but it does make you think about that tricky pop culture sci-fi mirror. Social change can be amplified by pop culture, and in that way, Star Trek is one of the best signal boosters of all time.

Social change can be amplified by pop culture, and in that way, Star Trek is one of the best signal boosters of all time.

Pre-21st-century Star Trek certainly showed a lot of bravery, but when it came time for gay characters to possibly appear in The Next Generation, that era of Star Trek failed to provide a meaningful mirror. When Roddenberry launched TNG, he promised his writers that writing about AIDS and homophobia would happen on his show. And why not? Star Trek: The Next Generation was a syndicated program and, as such, had fewer rules from Paramount about what they could and couldn’t do. If a local station didn’t want to carry the series because it depicted gay people, that was their business. And yet, with all that freedom, Roddenberry didn’t do it.

Infamously, “Trouble with Tribbles” writer David Gerrold wrote a script called “Blood and Fire” for TNG, which would have depicted gay crew members on the Enterprise while also tackling a kind of 24th-century version of HIV. Although Roddenberry claimed to support the script, the Great Bird of the Galaxy himself seems to be the person who shot it down, allegedly saying the script was “a piece of shit.” Gerrold mostly ascribes these viewpoints to Roddenberry’s manic behavior and substance abuse during the early years of The Next Generation, once recalling that “I don’t know how much [Roddenberry] drank because I never saw him sober.”

Others suggest that Roddenberry’s canceling of “Blood and Fire” can be attributed to his aggressive lawyer and puppeteer Leonard Maizlish. When Herb Wright was assigned to rewrite “Blood and Fire,” he learned that much of the negative notes supposedly written by Roddenberry originated, more likely, with Maizlish. And in 2014, David Gerrold himself blamed the “clusterfuck” on homophobia deriving from longtime Trek producer Rick Berman.

Still, regardless of whose fault it was, the fact remains that “Blood and Fire,” a Season 1 Next Generation episode set to depict gay people in the 24th century, never got made.[i] In the 2003 Enterprise episode “Stigma,” the Trek franchise asserted a vague HIV analogy; what if mind-melds were considered taboo among Vulcans at a certain point in history? Not only was this episode two decades after the dust-up involving “Blood and Fire,” it also failed to portray any gay characters.

In fact, after The Next Generation debuted in 1987, across four different Trek series for 18 years, all the way up to the year 2005, there was not one explicitly gay character from “our” universe. In Deep Space Nine, it was insinuated that series regulars Kira (Nana Visitor), Ezri Dax (Nicole de Boer), and Leeta (Chase Masterson) were all bisexual. Oh, wait a minute. Their evil duplicates from the Mirror Universe were bisexual! In the regular universe, they were not. These bisexual baddies also reinforced negative stereotypes that LGBTQ folks have looser morals, simply by virtue of being not straight. In terms of progress, Mirror Universe bisexual characters were more out, but not exactly good role models in the way other Trek characters are.

In 1992, you’d be hard-pressed to find another big TV show in which characters were having frank conversations about which pronouns they preferred.

Although characters on The Next Generation, Deep Space Nine, Enterprise, and Voyager were often coded or read as queer by the fans, none of the Trek series actually managed to depict an overtly non-straight character without some kind of twist or metaphor. Because of this fact, you can start to understand why Trek fans in 2018 felt like they’d had the rug pulled out from under them with Culber’s fake-out death. It’s bewildering and yet, somehow, predictable that prior to the 21st century, Trek only used analogies to talk about queerness.

For queer fans like S. E. Fleenor, this meant finding characters that were “coded” as queer. When I asked Fleenor about Seven of Nine’s queerness, they pointed out: “We can hold creators, including Gene Roddenberry, responsible for refusing to embrace queer and trans characters and story lines as more than subtext. Their queerphobia and transphobia outside the world of Star Trek had a huge impact on the world created within the narrative.” To their point, even with TNG, some of the attempts at writing toward gay rights issues ended up sending a mixed message.

Perhaps the most divisive episode of The Next Generation is the 1992 episode “The Outcast.” Written by Jeri Taylor, the episode introduces a single-gender alien species called the J’naii. On this planet, gender is considered “primitive,” and if individuals claim to have gender leanings one way or another, they are required to undergo “therapy,” which basically brainwashes them into the cultural norms of the planet.

Watching “The Outcast” today is a mine-field, partly because Riker admits to the guest character Soren (Melinda Culea) that he can’t figure out what pronouns to use if people aren’t either male or female. The most overtly heterosexual character on the ship of course falls in love with a nonbinary alien who, as it turns out, wants to declare their gender as female, which is forbidden by her culture.

Arguably, Taylor’s gay allegory was well-intentioned, but the writing feels directed at heterosexuals. Because a gay allegory was written for a straight audience, many of the queer people in the audience at the time were understandably offended. “We thought we had made a very positive statement about sexual prejudice in a distinctively Star Trek way,” producer Rick Berman said in 1992. “But we still got letters from those who thought it was just our way of ‘washing our hands’ of the homosexual situation.”

Jeri Taylor went on record saying “The Outcast” was intended as an “outspokenly . . . gay rights story.” But was it? Although the contemporary reputation of “The Outcast” is very mixed, the episode has gained some renewed praise in the 21st century. Writing for Star Trek.com in 2020, Nitzan Pincu points out, “By giving Soren the chance to rebel against her oppression, the episode voices a queer plea to free sexual ‘others’ . . . Her reprogramming illustrates the dehumanizing effect of conversion therapy, which was little known outside of the gay community at the time the episode aired.”

Even when Trek failed to provide real representation, “The Outcast” can be read as a case for allyship. As Pincu mentions, Worf initially presents a bigoted attitude toward the nonbinary J’naii, but by the end of the episode, he’s the one who decides to go against orders and help Riker rescue Soren. If the goal of “The Outcast” was to make antigay straight families uncomfortable in 1992 and give kids something to think about that broke through the sexual dogma they’d been taught, then the episode was successful.

I was 11 when the episode aired, and I specifically remember it challenging my assumptions about who Riker was allowed to crush on. The episode may not be remotely progressive by 21st-century standards, but Jeri Taylor’s heart was certainly in the right place. It may not be a moment to applaud, but I dare anyone to find another action-adventure series aimed at families, airing in 1992, that depicted the hunkiest straight dude in the universe falling in love with someone who is clearly queer, and in terms of a contemporary reading, clearly a trans character. Most of Soren’s conversations with Riker at the top of the episode are about pronouns. It’s clunky in 2022, but in 1992, you’d be hard-pressed to find another big TV show in which characters were having frank conversations about which pronouns they preferred.

___________________________

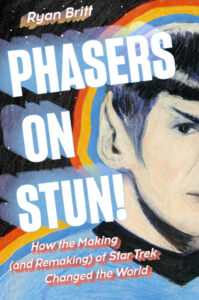

From Phasers on Stun!: How the Making (and Remaking) of Star Trek Changed the World by Ryan Britt. Copyright © 2022 by the author and reprinted with permission of Plume Books.

[i] In 2008, “Blood and Fire” was made as a fan film “episode” by James Cawley’s series Star Trek: Phase II, later rebranded as Star Trek: New Voyages. David Gerrold wrote and directed the piece, which retooled his TNG script into a TOS setting. In this version, Kirk’s nephew Peter Kirk was gay. It enjoyed in-person screenings at Star Trek conventions but existed almost exclusively online as a nonprofit fan film. In 2008, Paramount and CBS had to implement more draconian policies about fan films, meaning “Blood and Fire” probably couldn’t have been made today.

Ryan Britt

Ryan Britt is an essayist, critic, fiction writer, storyteller, and teacher living in New York City.