Who is the Narrator of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time?

Saul Friedländer on the Many Functions of the Most Elusive

Figure in French Literature

There have been many attempts to define the “Me” used by the Narrator in Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. As the linguist Leo Spitzer put it, “this Me seems to be situated at greater depth [than the narrating Me and the acting Me]; he has left the surface of the story in an inaccessible deep level” (I thank Carlo Ginzburg for drawing my attention to the importance of this essay).

Another more recent attempt at definition, with which I partly disagree, will be of indirect help: Brian Rogers’s essay on “Proust’s Narrator” in the Cambridge Companion to Marcel Proust.

“The Narrator is not Marcel Proust,” Rogers writes. “He often borrows the eyes and the ears of the author and seems to possess the same encyclopedic culture. But he is only a character in a story and his story contains only one event, the decision to write a book . . . The reader must take on trust what the Narrator chooses to tell us about himself. He has no name, we have no clear idea what he looks like. For long stretches of his book he disappears from view, leaving the reader to eavesdrop on conversations of people who seem oblivious of this man’s existence. He is passive and transparent, everywhere and nowhere, sometimes a spy, often a voyeur turning up in unlikely situations, a disembodied presence unlike that in any novel before. But the mirror he offers the reader is so fascinating that we not only enter the world reflected in it, we inhabit the Narrator’s body, see everything through his eyes and share his sensibility.”

If the Narrator was just expressing what one knows of the author’s views, emotions, and attitudes, Rogers would be right. But the Narrator has a mind of his own, so to speak, and often conveys views one doesn’t expect, views that may have escaped the author’s mind and heart. Thus at times he looks like Proust’s unconscious, independent from the author’s conscious ego—and there I agree with Spitzer’s attribution of great depth to the Narrator’s “Me”—that suffices to give him a personality of his own. He has become a character among the characters of the novel. Even when he doesn’t escape the author’s surveillance, he doesn’t look like the author’s mere shadow.

*

From the very first lines of the novel we see the child struggling with sleep or disoriented for a moment when waking up, we see him listening to his great-aunt as she shows him Golo’s sinister figure and Geneviève de Brabant’s castle on the magic lantern, while she tells him the story; we see and feel his distress when his mother cannot come up to his room to kiss him good night, and so on. We follow the stages of the Narrator’s life: we are informed about his feelings, about the books he reads, the walks he takes, the conversations he has; we encounter his first loves, we are told of his earliest sexual experiences, in short we follow the growth and evolution of a very specific character whom we tend to identify with the author, although we know that it isn’t always he. And we know exactly the physical sensations that trigger the Narrator’s sudden recognition that he can become the writer he dreamt of being and despaired of ever becoming. In the figure of the Narrator, any reader familiar with Proust’s life will easily recognize what belongs to that life and when something else is at work.

Even when the Narrator doesn’t escape the author’s surveillance, he doesn’t look like the author’s mere shadow.The Narrator hasn’t been created only to offer a mirror in which several hundred characters are reflected. At times he does hold that mirror, but as I have stressed, he also takes on an autonomous role and often expresses himself in encrypted messages. Moreover, he stumbles at times into revelations or pseudo-revelations that certainly tell more about the author than the author may have wanted his readers to know. In other words, the Narrator performs multiple functions, some of which we cannot foresee. In this unintentional role, he is like the golem who, in a famous Jewish legend, has escaped from the rabbi who created him and starts destroying the defenses the rabbi had erected against himself and against the enemy.

*

Proust may not have welcomed the metaphorical rabbi, and he probably would have considered the golem only a helpful instrument. He tried to write an autobiographical novel, Jean Santeuil, but didn’t complete it. Doing so may, among other difficulties, have limited the material he could use in the future. Thus, if he wanted to be free to rework most of the huge amount of his stored observations, he had no other choice but to invent a fictional Narrator as his alter ego. But in a fiction driven by personal memory, and at times by involuntary memory, the inherent dynamic of such narration could and did lead beyond the limits set by the author. More often, of course, the author could send, quite intentionally, what I called “encrypted messages” in order to convey what he wished to convey to a select readership. And at other times he pressed the wrong button and a flow of revelations came tumbling down.

Fundamentally, when the author holds the reins, the Narrator fulfills a dual main function: he is the dreamy conveyor of an emotional world, that of childhood, of loves and of pain; he is also the sharp observer of the social currents that swirl around him. As a dreamer, he can unveil aspects and puzzles of the unconscious; as an observer, he is allowed to ferret out the most ridiculous features of the puppets strutting on the social stage, and also their darkest secrets.

*

This dual persona allows him to move from one world to the other and hold the whole story together.

It is around the sexual domain in general that the Narrator’s allusions or equivocations are the most significant ways of revealing what he otherwise denies, as I indicated already in the chapter on forbidden love. Here I shall merely look again at the Narrator’s chance visit to Jupien’s homosexual brothel. The visit, triggered by the flimsiest of narrative inventions—thirst—is a barely hidden allusion to Proust’s apparently regular attendance at Le Cuizat’s quite similar institution. The detailed description of the goings-on inside the brothel proves to the most-naive reader that the Narrator is well acquainted with that exclusive drawing room. As for the repeated worry of all those concerned, clients, staff, and manager, about absolute discretion and the camouflage of clients’ identity, isn’t it an oblique reference to the author’s similar worry, mainly after having been caught at least once in police raids?

No less significant is the allusion to Charlus’s nickname among the staff, “the man in chains”; it is not too far away from Proust’s nickname at Le Cuizat’s place: “the rat man.” (No allusion here to Freud’s famous case, but rather, as already mentioned, to the habit the author confessed to André Gide, if orgasm could not be otherwise achieved.) Finally—and this may be the most significant allusion—in his mulling over the relations between Charlus and Morel, and after having assumed that Morel may have withheld all physical pleasure from the hungry baron, the Narrator comes to the conclusion that in any nonreciprocal love relationship, the partner who refuses to grant the sexual demands of the other holds the psychological advantage and can actually enjoy all the benefits of a generosity that will be more rewarding than it would have been in a fully reciprocal situation. The Narrator isn’t merely referring to the baron’s love for Morel; he is very precisely describing Proust’s unrequited passion for his driver and later secretary, Alfred Agostinelli.

*

And incidentally, don’t the Narrator’s allusions add some interesting details to the autobiographical dimension of the novel?

When the author holds the reins, the Narrator fulfills a dual main function: he is the dreamy conveyor of an emotional world and is also the sharp observer of the social currents that swirl around him.Another function of the Narrator is, it seems to me, to be a sort of hyphen between the main characters and their distant past, thus giving to the immense story a further coherence and some of the harmony necessary to keep control over its expanse and its many facets. At times the Narrator points to the essential role played by a character in his own evolution, in the very genesis of the novel to be. Such is, for example, the role he attributes to Swann:

It occurred to me, as I thought about it, that the raw material of my experience, which would also be the raw material of my book, came to me from Swann, not merely because so much of it concerned Swann himself and Gilberte, but because it was Swann who from the days of Combray had inspired in me the wish to go to Balbec . . . and but for this I should never have known Albertine . . . Swann had been of primary importance, for had I not gone to Balbec I should never have known the Guermantes either, since my grandmother would not have renewed her friendship with Mme de Villeparisis nor should I have made the acquaintance of Saint-Loup and M. de Charlus and thus got to know the Duchesse de Guermantes and through her her cousin, so that even my presence at this very moment in the house of the Prince de Guermantes, where out of the blue the idea of my work had just come to me (and this meant that I owed to Swann not only the material but also the decision), came to me from Swann.

In other words, the Narrator, thanks to his ubiquity, allows the author to present various facets of Swann and any other of his characters as seen by diverse protagonists and over any length of time. As Vladimir Nabokov puts it, “one essential difference exists between the Proustian and the Joycean methods of approaching their characters. Joyce takes a complete and absolute character, God-known, Joyce-known, then breaks it up into fragments and scatters these fragments over the space-time of his book. The good rereader gathers these puzzle pieces and gradually puts them together. On the other hand, Proust contends that a character, a personality, is never known as an absolute but always as a comparative one. He does not chop it up but shows it as it exists through the notions about it of other characters. And he hopes, after having given a series of these prisms and shadows, to combine them into an artistic reality.”

This effusive attribution to Swann of paternity for the novel confirms, to a point, the Narrator’s dual vision of Jews: on the one hand, the “shtetl,” the Jewish crowd, the petits juifs (Bloch), on the other hand, the “grands Israélites” (Swann), a sarcastic distinction we owe, much later, to the novelist François Mauriac, but one that reflected, even after World War II—and certainly before and during the war— the self-perception of most French “Israelites.” It was an obvious self-perception during the earlier decades of the twentieth century, certainly as seen from the vantage point of the author and the Narrator.

Yet whatever the social context of the Narrator’s perception of different strata of the Jewish community may have been, he seems benevolent at times regarding the Jews as a distinct and persecuted entity. Thus, as he observes a weary Swann, stricken by terminal cancer, at the reception in the Prince de Guermantes’s palatial home, his thoughts turn to Jewish fate: “Swann belonged to that stout Jewish race, in whose vital energy, its resistance to death, its individual members seem to share. Stricken severally by their own diseases, as it is stricken itself by persecution, they continue indefinitely to struggle against terrible agonies which may be prolonged beyond every apparently possible limit, when already one can see only a prophet’s beard surmounted by a huge nose which dilates to inhale its last breath, before the hour strikes for the ritual prayers and the punctual procession of distant relatives begins, advancing with mechanical movements as upon an Assyrian frieze.”

At times, the Narrator functions as an “enabler” of encounters that shed some additional light on characters we thought we knew well but who suddenly appear somewhat different than what we imagined. Take, for example, the conversation between Charlus and Brichot as they are about to leave a dinner at the Verdurins’; the baron tells us about aspects of Swann’s personality that we didn’t know. And this conversation as such is facilitated by a previously ongoing discussion between the Narrator and Charlus that Brichot joins. We knew that Swann was intensely jealous of the “attention” other men granted to Odette in the early period of their relationship, but we didn’t know that he fought a duel with one of those admirers on one occasion (as the author once did, albeit for a different reason) or that he took Odette’s sister as his mistress to convey his fury as a result of Odette’s infidelities.

Another function of the Narrator is to be a sort of hyphen between the main characters and their distant past, thus giving to the immense story a further coherence and some of the harmony necessary to keep control over its expanse and its many facets.Mostly, however, the Narrator listens and reports what he hears, an essential function in a novel based more on conversations than on anything else. But the Narrator’s acrobatic listening, as at times he pays attention to several simultaneous discussions or monologues, is constantly interspersed with his own short answers and mainly with his silent observations on what is being said or done all around him. Thus, in the midst of a conversation with the terminally ill Swann at the Prince de Guermantes’s reception, the Narrator follows his interlocutor’s gaze suddenly fastening upon the beautiful Marquise of Surgis-le-Duc, as he rises to greet her: “as soon as Swann, on taking the Marquise’s hand, had seen her bosom at close range and from above, he plunged an attentive, serious, absorbed, almost anxious gaze into the depths of her corsage, and his nostrils, drugged by her perfume, quivered like the wings of a butterfly about to alight upon a half-glimpsed flower. Abruptly he shook off the intoxication that had seized him, and Mme de Surgis herself, although embarrassed, stifled a deep sigh, so contagious can desire prove at times.” And the conversation, briefly interrupted, goes on.

*

This short scene and its opening paragraphs perfectly exemplify the Narrator’s role and his extraordinary agility in fulfilling it. As the Narrator is conversing with Swann, he cannot help hearing the Baron de Charlus talking to Mme de Surgis, which leads him (the Narrator) to give us a rapid summary of Surgis’s past, of the origin of her name, of her move, twice over, from the height of society to its bottom and back, in between Charlus’s continued flood of comments about a painting that had belonged to the Surgis family, his alluding to Vermeer as he recognizes Swann, whom Surgis then greets, which leads to the scene above and to the Narrator’s remarks about the contagion of sexual desire, before he resumes the interrupted conversation with Swann.

The conversation that follows shows a different facet of the Narrator’s role in the overall structure of the novel. As he resumes talking to Swann, the Narrator asks him about the truth in what is being hinted regarding Charlus’s sexual preferences. Swann denies the evidence, which was well known to the Narrator, who had witnessed a love-making scene between Charlus and Jupien. In the following part of the conversation, Swann confides to the Narrator the Prince de Guermantes’s and his wife’s belief in Dreyfus’s innocence. Nobody else knows of it. Thus, in regard to the private lives of the characters and their public personae, the Narrator ultimately is the one who knows both the false appearances and the facts about each of them. The Narrator is the depositor of all the falsehoods swirling around and, sooner or later, of the facts as far as they can be known. In Search is no Rashomon: the author remains within the boundaries of a realism that he otherwise denounces.

Although conversations are arguably the essential stuff In Search is made of, they are encased in a myriad of observations about the characters, of course, but also by a myriad of descriptions of the surrounding world, the beauty of which, as transmitted by the Narrator, is overwhelming. It is this sheer magnificence that endows the novel with an unusual power, holding the reader in its embrace throughout an immense journey. And it is the Narrator who conveys to us that iridescence of all things. But could it be that, here, too much beauty is the trouble?

__________________________________

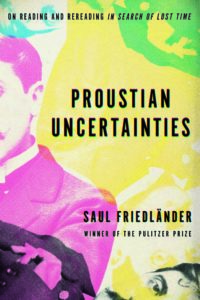

From Proustian Uncertainties: On Reading and Rereading In Search of Lost Time by Saul Friedländer. Used with the permission of Other Press. Copyright © 2020 by Saul Friedländer.