Who Are the Leo DiCaprios of the Booker Prize?

Lucia Tang on the Perpetually Snubbed

Three years ago, the internet collectively decommissioned a well-worn meme: Leonardo DiCaprio Gets Snubbed by Oscar. After four fruitless nominations, the perennial Academy also-ran finally scored a golden statue of his own. In response, the enterprising artists of Tumblr and Twitter publicly retired a half-decade’s worth Leo edits: mournful, Aloha-shirted Romeo clutching the statuette; amorous Jack with one hand resting on a Rose-sized Oscar’s waist; quaalude-addled Jordan Belfort, crawling after a trophy that just keeps receding towards the edge of the gif.

Anglophone literature’s Oscar equivalent, the Booker Prize, isn’t quite as memegenic as the Academy’s rock-abbed homunculus. If the trophy looks like anything, it’s an overfed comma, and it’s hard to imagine anyone Photoshopping one into the arms of a disappointed author. But there are a handful of living novelists who—like pre-Revenant DiCaprios—keep catching the judging panel’s eye without snatching the prize.

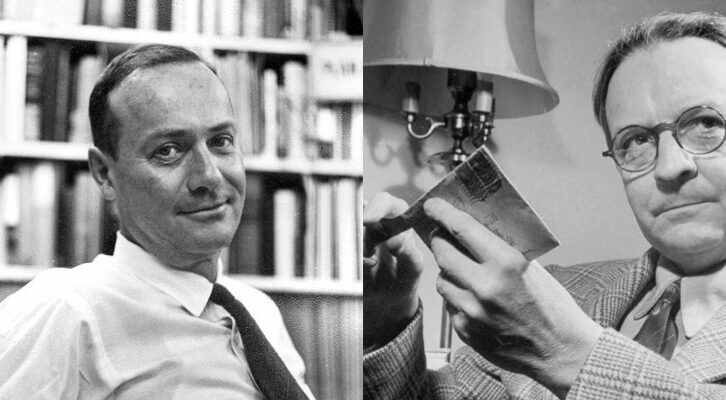

The Booker hasn’t been wholly oblivious to the peculiar plight of its literary Leos. The 2011 judges made a point of addressing their predecessors’ contentious history with the English novelist Beryl Bainbridge. The dark wit and psychological incisiveness of her oeuvre earned her a record five nominations, but she watched the trophy slip from her fingers every time.

Over the years, Bainbridge acquired a bittersweet reputation as the “Booker bridesmaid.” So the committee announced a one-time “Best of Beryl” Prize. In a break from typical Booker protocol, they pitted Bainbridge’s five shortlisted titles against one another in an American Idol-style vote, letting the thousand readers who responded crown 1998’s Master Georgie.

To her most vocal devotees, this Greatest Hits award was too little, too late—Bainbridge had passed away the previous summer. Booker’s tribute to her registered to them as patronizing,”tacky,” even “somewhat creepy.” But the Prize committee has a chance to redeem itself with the oft-nominated and never-victorious authors still working—the new Booker bridesmaids to whom Bainbridge has posthumously tossed the bouquet.

The dark wit and psychological incisiveness of Beryl Bainbridge’s oeuvre earned her a record five Booker nominations, but she watched the trophy slip from her fingers every time.

Among this cohort is Ali Smith, Scotland’s widely adored “Nobel Laureate-in-waiting.” Over the course of her 19-year literary career, she’s garnered four nominations, starting with 2001’s Hotel World. Will she capture the Prize before she’s summoned to Stockholm? Smith’s ambitious Seasonal Quartet—four loosely connected novels that flit gracefully from Shakespeare to post-Brexit xenophobia—seems promising. Autumn, 2016’s installment, earned Smith her most recent berth on the Booker shortlist, and the forthcoming Summer offers a perfect opportunity for getting that trophy in her hands at last.

The committee started releasing its longlists to the year of Smith’s first nomination. Since then, another author has emerged as the current Booker bridesmaid par excellence: English speculative fiction writer David Mitchell. Longlisted three times and shortlisted twice, he’s just crossed the Bainbridge threshold. And with seven novels in print, he boasts an absurd nomination rate of just over 71 percent.

For Mitchell, the Booker nods have come on thick and fast. Starting with his sophomore novel, 2001’s Murakami-esque number9dream, he’s been nominated for five consecutive books. This dizzying pace recalls an author honored among this year’s Booker Dozen, the South African-born British writer Deborah Levy. Her last three titles have all been in the running; the previous two—unlike this year’s The Man Who Saw Everything—made it all the way to the final six.

Like Bainbridge before them, Smith, Mitchell, and Levy clearly have the Prize committee’s love—up to a certain point. Is it all a matter of small sample sizes and Janus-faced luck? Or is there something about their work, and the Booker Prize’s tastes, that explains why the committee keeps stringing them along? Asking this question feels as muddle-headed as wondering why the Academy votes the way it does: of course it’s an unsatisfying mixture of art and reputation. But the Booker—like the Oscar—has a sensibility, a repertoire of shticks that endures even as the judging panel keeps changing.

What makes a novel Booker bait? Prodigious length—though Lucy Ellmann’s 1,034-page Ducks, Newburyport, from this year’s shortlist, represents an extreme. High-concept structural conceits, like Ellmann’s interminable, Ulysses-sized sentence, help. The committee also seems to favor magical realism delivered with a haute-literary touch. They like their writing rococo, overstuffed with detail. And, like the Academy, they evince a soft spot for plush period pieces.

After years spent racking up op-ed charges of snobbery, the Prize has tried to reinvent itself—to a point. This year’s Booker Dozen includes one novel, at least, that reads like anti-Booker bait. Oyinkan Braithwaite’s My Sister, the Serial Killer is a slim, dynamic masterpiece, leaning in hard on its pulpy genre influences. Braithwaite’s Booker nod seemed to signal a shift in taste. But ultimately, the committee didn’t send it to the shortlist—which comprises, for the most part, the usual kind of fare, from Ellmann’s thousand-pager to 1981 winner Salman Rushdie’s Quichotte, a Don Quixote redux with the obligatory metafictive structure.

In the past, critics have wondered if Bainbridge’s novels, while too good to snub entirely, were too short and straightforward to offer the crown. Deborah Levy produces work that, while stylistically distinct from Bainbridge’s, is comparably tight—and turns a comparably sharp eye on often twisty relational dynamics. Bainbridge’s fellow five-timer David Mitchell, for his part, may simply be too geeky, too genre for the Booker’s tweedy tastes. After all, he’s a World Fantasy Award winner who appears on “best of sci-fi” lists shoulder-to-shoulder with the likes of Asimov and Dean Koontz—he even wrote for a Wachowski-led Netflix original.

Then there’s Ali Smith, whose highly stylized, thematically omnivorous work certainly feels peak Booker. Maybe it’s just bad luck. But maybe Summer’s going to be her season.

Lucia Tang

Lucia Tang is a writer and historian who works on books, literary culture, and the pop-cultural reception of premodern China. She lives in Berkeley, California.