Where the Hell Do You Start With Something as Vast as a Memoir?

iO Tillet Wright on How to Tell the Story of a Life

I’ve always dreamt of writing a memoir. It’s one of those things—you have a crazy life, you know how to string a coherent sentence together, people tell you that you should write a book—and yet, Darling Days wasn’t my idea. I had done a TED talk and I’d asked a friend’s fiancée to connect me to the speaker’s department at his agency. Turns out he was a literary agent and wanted to see if I had any chops. He had NO idea how crazy my life had been. “Sit down and start writing and see how it feels,” he said. Ok, I thought. What image comes to mind most vividly? My mother, in the bed she shared with her common-law husband, in the East Village in the 1980s, sleeping with a pistol under her pillow. She pulled that pistol on a junkie crawling through the window once, because she was afraid he’d steal her lipstick.

I wrote a half page. I tried not to stress that it wasn’t some long piece, and sent it to my friend’s future husband with internal fingers crossed. “Oh! You’re a writer!” he wrote back. “Keep going!”

Ok, well, where the hell do you start with something as vast as a memoir? At the beginning. So I started to write the story of my birth, as my parents had told it to me hundreds of times, then I just kept going.

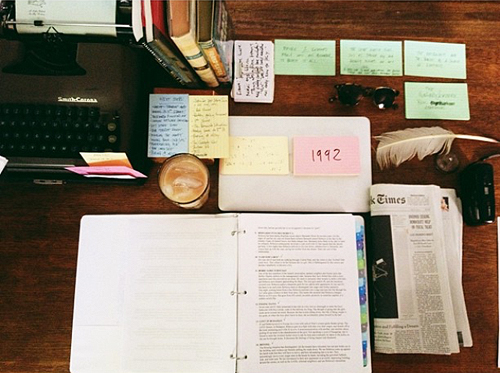

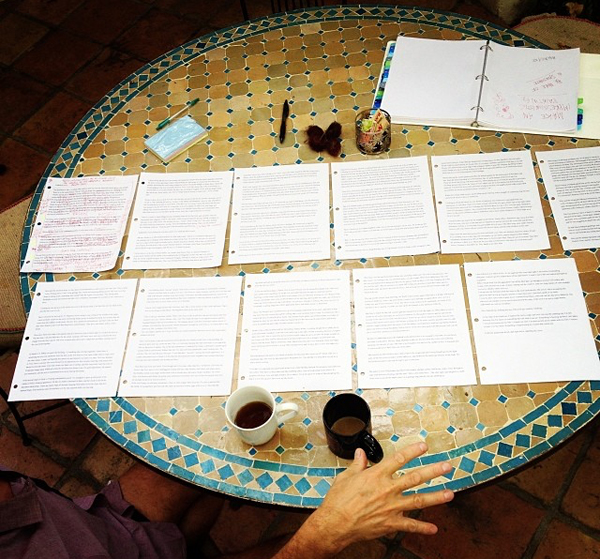

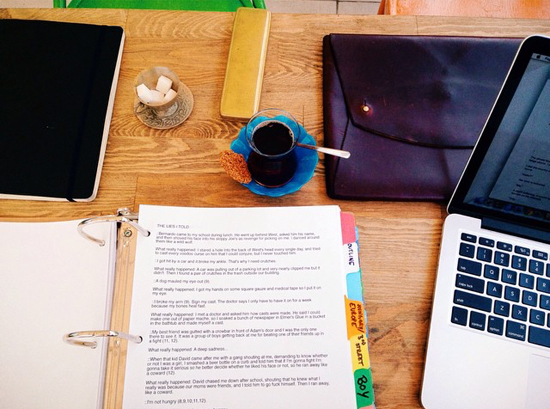

I started by making a long list of every event I could think of that felt important enough to relay to a reader who had never met me, then made a peg board of index cards, a scene per card. I shuffled it around a ton, and pulled things off when they got the can. Over the course of a year, I wrote 53 vignettes, some of which were one page, some that were 18, describing instances I thought might be relevant. I didn’t write them in chronological order, though I knew I wanted them to end up that way.

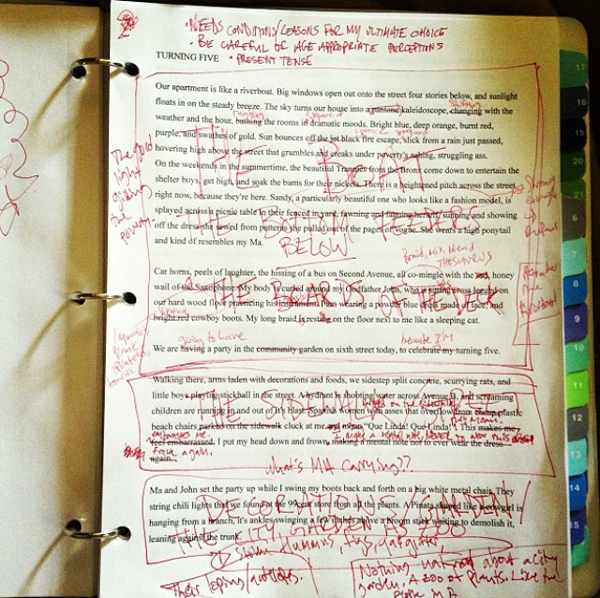

I ended up with 140,000 words—a hulking goliath of a manuscript, the last third of which I wrote in one terrific final push, like the last shove of a woman in labor. I needed to get the thing out, and it just so happened that the darkest parts came last, so I had to shred my insides to relive those moments in the first-person present and I was eager to push through. Turns out the writing sucked. I sent it to my father, always my first-pass editor, and he pointed out how lazy and rushed it was. I didn’t want to hear it, but he was right. I went back and walked barefoot through the shards of traumatic memories, slowly this time, paying attention to the details. I pulled out old photographs and studied the things in each room I was in. I searched my own eyes for evidence of my anguish as a teenager, and it was all there. Adult me sat in my house and sobbed onto my keyboard as I rewrote scenes with heart and feeling. I came out of it a different version of myself, wounds that I didn’t even know I had carried freshly formed scabs.

One of the gnarliest pieces of writing in the book came during an awful period when I was 28, during which I was suffering from crippling bouts of anxiety and depression. I was in a meeting in LA and ran outside to sit alone in my car, plagued by a surging sense of panic and fear, the root of which I had no hint of. I whipped out my phone and furiously began typing into a note, describing how I felt. It became a chapter where I describe in more poetic terms, what it feels like to be inside my mind at its worst.

I also pulled an entry out of my Third Grade Year Book, which I discovered on a shelf in my Elementary School Library and copied it verbatim into the book.

Some night I might

Slip away in the moonlight.

Some night I might

But not tonight.

I went back to the family court building where I was taken when I was removed from my mother’s care, for the first time since it happened 19 years ago. I stood outside and looked at the architecture. I put my hands up on the glass, studying the lobby for details that I spoke into my recorder, and cried. My memory of the place from when I was 12 was perfect, photographic, as traumatic ones sometimes are.

Reliving the heaviest moments of my life and transcribing them to the page let me walk through things that I had long since buried. That might sound excruciating, and at times it was, but ultimately, it gave me a place to put it all, a shelf to organize it on, and a light switch to flick off in a dank room that had only been a pile of rubble before without a door that would stay closed.

iO Tillett Wright

iO Tillett Wright is an artist, activist, actor, speaker, TV host and writer. iO’s work deals with identity, be it through photography and the Self Evident Truths Project/We Are You campaign or on television as the co-host of MTV’s Suspect. iO has exhibited artwork in New York and Tokyo, was a featured contributor on Underground Culture to T: The New York Times Style Magazine, and has had photography featured in GQ, Elle, New York Magazine, and The New York Times Magazine. iO is a regular speaker at universities, discussing expanding one’s circle of normalcy and embracing those that are different than you. A native New Yorker, iO is now based in Los Angeles.