Where the Grass is Greener: 5 Irish Tales of Straying Wives

Molly McCloskey on the Descendants of Molly Bloom

There’s a long-standing joke in Ireland, which harkens back to a lament by a conservative politician in 1967, that before television, there was no such thing as sex in Ireland. This is not, of course, quite true, but sex certainly wasn’t a thing much discussed: Irish writers were heavily banned in their own country, and the bar for salaciousness was low. Women having sex was an even greater taboo, and adulterous women more scandalous still. When I set out to write a novel about a young American woman who has an adulterous affair in the west of Ireland in the 1990s, I thought about how her Irish counterparts had fared down the decades, both when the Catholic Church and the Irish State—those twin arbiters of shame—held the country in their grip, and once that grip had loosened. Presiding over any such gathering must be Molly Bloom, the ur-adulteress of 20th-century Irish fiction, the patron saint of straying women. Here are five great post-Ulysses Irish takes on adulteress wives.

Love and Summer, William Trevor

As discreet in its treatment of infidelity as Ulysses is ribald and naughty in its, Love and Summer was Trevor’s final novel. Set in the 1950s, in the stifling fictional Irish town of Rathmoye, it traces the effects of an affair on its heroine Ellie Dillihan. Ellie falls in love with Florian, a young man passing through, and undergoes a sensual and existential awakening. Trevor is fantastic on the brevity of pleasure and the long life of memory. (In the same vein, see his wonderful short story, “A Bit on the Side.”) Ellie’s happiness is brief and bracketed, but what’s left in its wake is not resentment or emptiness but rather bittersweetness and a kind of grown-up love. This is a novel about adultery that turns, ultimately, into a story of compassion.

The Forgotten Waltz, Anne Enright

Enright’s wonderful novel is about an extra-marital affair in Dublin that runs parallel to the amorality and hedonism that was the Celtic Tiger. As with the so-called boom years, which left the country bankrupt (the sense of a mammoth hangover was undeniable), there is, for Enright’s lovers, an intoxicating headiness to the lust and self-indulgence that comes with an affair. And then there is the aftermath: mundane reality, and all the debts to pay. Pulling the house down around you, in this case, means a lot of mortgages to sort out. Wickedly funny, but with an ache of melancholy running through it, this novel is quietly radical in its way: in the end, the adulterous Gina gets what she wants.

Ancient Light, John Banville

Ancient Light tells the story of an affair between a teenaged Alexander Cleave and the married Mrs. Gray, twenty years his senior. Set in the 1950s, the novel is told from Cleave’s point of view, and is more about what the affair meant to him than it is about Mrs. Gray, but Mrs. Gray is transfixing, a still point of desire who has poor Alex “quivering like a gun-dog with expectancy.” Why Mrs. Gray does what she does, and why she’s so heedless of the consequences, becomes clear late in the novel. The erotic is rendered with Banville’s signature meticulousness, and the whole book feels steeped in a peculiarly post-coital sense of loss.

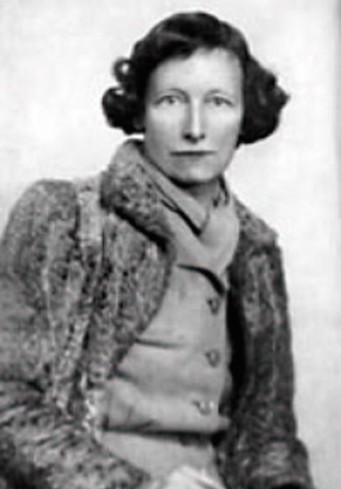

“Nine Years is a Long Time,” Norah Hoult

This is a short story, but I’m including it because it’s such a strange and singular work, written by a woman whose fiction, once heavily banned and now largely forgotten, seems to be creeping in from the margins. Hoult was born in Dublin in 1898 and lived her life between Ireland and England. “Nine Years is a Long Time” is the tale of a married woman and her nine-year affair with a mysterious man. With the money from her lover—three pounds a month—she helps support her parasitic husband and her moralizing daughter. This is a destabilizing read: what’s normally hidden is overt (the enabling spouse made explicit), the ordinary lies of adultery are redirected, and power is tricky to pin down. There are layers of reveals and reversals—all subtly rendered. To say “unsentimental” would be putting it mildly. This is a harrowingly good story.

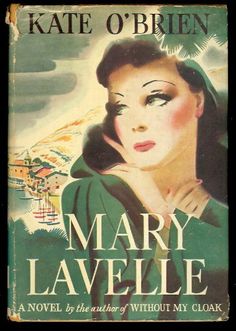

Mary Lavelle, Kate O’Brien

The eponymous Mary is engaged to a man who was won her heart, without, O’Brien notes, having disturbed her senses. Before tying the knot, she travels to Spain to work as a governess—to see something of life, to “hide awhile from even the most agreeable certainties.” Enter the married Juanito. Mary grows up fast, not because Juanito initiates her into carnal pleasures (the sex itself is cringe-inducing in its emphasis on female surrender and male pleasure), but because she gains a clear-eyed insight into the seriousness of her emotions, while accepting the need to walk away—crucially, not back to her fiancé. O’Brien’s novel, banned in Ireland for more than 30 years, celebrates Mary’s “pagan” sensuality as against the Catholic moral order, and makes clear that self-knowledge is the prize worth winning.

Molly McCloskey

Molly McCloskey has served as writer-in-residence at Trinity College Dublin and University College Dublin. She is the author of three works of fiction and the memoir Circles Around the Sun: In Search of a Lost Brother. Straying is her first work of fiction to be published in the US. She is a citizen of both Ireland and the US, and she now lives in Washington, DC.