Where is the Power in Mass Protest?

Lessons from Ukraine and the Euromaidan

Three years ago, on November 21, a small group of students gathered in central Kiev to protest Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal to sign an EU Association Agreement. After the violent dispersal of the demonstrators on November 30, the protests—named “Euromaidan” for their site, Maidan Nezalezhnosti, Independence Square—became a mass movement. Thousands of Ukrainians occupied the square, setting up a tent city complete with makeshift barricades and simmering cauldrons of borscht. The protesters hoped to make Ukraine a “normal, European country,” rather than a corrupt vassal of Putin’s Russia.

Today, results are mixed. Yanukovych fled, a new president was elected, and reformers received prominent government posts. But Russia annexed Crimea, and Russian-backed separatists began a war in eastern Ukraine that has cost thousands of lives and displaced nearly two million people.

Nevertheless, the Maidan revolution remains an extraordinary example of the power of mass demonstrations. Its lessons have special importance today, when the US seems to be entering a new era of political protest. (Just last month, North Dakota law enforcement used water cannons on Standing Rock protesters in freezing temperatures—a potentially lethal tactic employed by Ukrainian law enforcement on Maidan protesters.) To what extent can a society be transformed by mass protests, by the sustained occupation of a public space? What happens when protests escalate into violence? And what comes after the revolution?

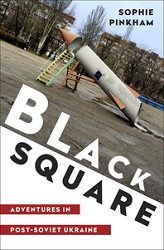

The following is adapted from Sophie Pinkham’s Black Square: Adventures in Post-Soviet Ukraine.

* * * *

Early on the morning of December 11, 2013, with the temperature down to nine degrees Fahrenheit, troops surrounded Maidan and tried to clear its periphery, though not its center. Protesters gathered to hold the square.

“That was the point of no return for me,” said my old Russian teacher, Vakhtang. “We all thought we could sleep that night—we’d been up for days. I went home and had some vodka, worked on a philosophy article, and went to bed. Then, just as I was falling asleep, a friend called and told me to turn on the TV. I saw that the riot police were trying to clear Maidan. . . . I was back there by one-thirty. People were unarmed, holding the police back with their bodies. Some people had their ribs broken by the pressure. At first there were only about three thousand people. And then suddenly there were twenty thousand. Taxis brought people there for free and the churches rang their bells, summoning everyone to Maidan. I understood that there would be a violent confrontation.”

“When we heard about the first clearing of Maidan—someone called—we ran down right away,” said Lena Grozovska, a calm, pleasant woman I knew from the Kiev art scene. “On the street we met people who told us to turn back. There were so many riot police officers, but there were also so many others—hipsters, bon vivants, designers, all kinds of people you’d never have expected, locking arms and blocking the riot police. The police looked like black caviar, with their helmets. When you looked into their eyes you saw such hate—they were such frightening people. A horde.”

Stuck in New York, I spent most of that night watching a live feed from the helmet camera of Mustafa Nayyem, the journalist who’d helped organize the first protests on Maidan. Together we climbed over barricades and ran down dark, snowy streets, through huge crowds. I listened as Nayyem talked on the phone, or asked for information, or bumped into people he knew.

In the end, the riot police were ordered not to attack. They cleared the barricades around the square, but the protesters rebuilt them the next day, passing sandbags full of snow along a human chain. “Now our greatest fear is cops with hair dryers,” my friend Aleksandr joked. The police tried to raid occupied City Hall, but the protesters held them off with hoses, firecrackers, and smoke bombs, coating the steps of the building with ice and oil.

* * * *

In an attempt to counter the massive demonstrations, the government set up an anti-Maidan camp with paid protesters. Acts of violence against Maidan activists proliferated. An anticorruption activist was shot in Kiev, his car set on fire. A well-known investigative journalist was chased down in her car, beaten and left for dead.

On January 16, the Yanukovych administration passed laws making it illegal to blockade government buildings, wear masks or helmets, install tents and stages without permission, or slander government officials. Suddenly everyone on Maidan was a criminal. These “dictatorship laws” prompted yet another enormous protest, which included an appearance by the investigative journalist, her face still battered.

Full-blown riots erupted outside government buildings near Maidan. Two protesters were shot dead—it was unclear by whom. Activists who went to hospitals for treatment started vanishing. Two kidnapped protesters were found in the woods a day after their disappearance; one had frozen to death after being tortured.

PartKom, a gallery where I’d often hung out with musician friends when I lived in Kiev, turned into an underground infirmary. My friend Alik started carrying a guidebook on wartime field surgery—he was following in the footsteps of his Jewish grandmother, who’d been a Soviet field surgeon in the Second World War. At one point he stitched up a right-wing nationalist with a swastika tattoo on his back.

“You know I’m a Jew, brother?” he asked his patient.

“Oh, I don’t hate Jews,” the wounded man replied. “Only niggers.”

* * * *

From the first weeks of Maidan, it had been clear that not all the protesters were content with peaceful methods. Right Sector was a far right coalition that sprang up in the early days of Maidan. On the night of November 29, Right Sector members in masks were spotted carrying truncheons, ready for a fight. The next day they organized a training on how to counter police attacks using impromptu weapons. Nationalist groups on social networks shared information on how to make your own arms and armor.

Some protesters threw bricks, and masked men threw Molotov cocktails; police responded with stun grenades and smoke bombs. On December 1, a group of radical nationalist protesters used sticks, stones, and ladders to attack riot police officers who were guarding central Kiev’s Lenin statue. The officers responded with tear gas and flash grenades. The protesters managed to push the police back, but two officers were left behind and beaten by the mob.

Opposition leaders were eager to maintain Maidan’s reputation as a purely nonviolent movement that deserved the wholehearted support of the West. They disavowed the violent protesters, calling them provocateurs: agents of Russia or of the Yanukovych administration, trying to discredit the demonstrations. But in a grassroots protest movement that was largely spontaneous, it’s hard to understand how opposition spokespeople could know that violent protesters weren’t authentic; they never presented any evidence that the masked men with Molotov cocktails were paid, for example. Right Sector had made little effort to conceal its fondness for physical confrontation.

Still, the EU and the United States continued to refer to Maidan as an entirely nonviolent movement. It was funny, with memories of Occupy Wall Street still fresh, to imagine what the United States would have done if protesters had occupied New York’s City Hall, thrown Molotov cocktails at police, and made a barricaded tent city in Times Square.

* * * *

On January 22 the police were authorized to use water cannons. By now protesters tossed Molotov cocktails freely, repurposing Kiev’s empty vodka and beer bottles for revolution. Women formed lines, pulling up cobblestones and passing them along to be thrown at the enemy. One of the self-appointed opposition leaders announced that the protesters would attack if their demands weren’t met within twenty-four hours.

At first only extremists had been willing to resort to force; now, outraged at the government’s willingness to torture or kill unarmed citizens, many people were coming around to the idea of armed resistance. The uncompromising men of Right Sector began to look like heroes rather than provocateurs. Sasha Volgina, my Russian AIDS activist friend, had moved to Kiev, where she was living with her Ukrainian husband. In the years since I’d first met her in 2006, many of her fellow Russian activists had died of AIDS-related illnesses or overdoses, often because of Russia’s refusal to provide decent medical care. Sasha was furiously in favor of Maidan, working at one of the first aid points. After the police turned violent, she wrote on Facebook,

Rights are not given, but taken. Sometimes roughly. The government has a monopoly, a mandate on the use of violence. As citizens, we delegated that right to the government. But not for use against its own citizens. So we’re retaking the right to self-defense, with cobblestones in hand.

* * * *

Others announced their willingness to die for the cause. One protester’s plywood shield bore the message, mother i will die for you but i will not give up in shame here. for our ukraine and for our forefathers i will not leave maidan without victory. His full name and phone number followed, so that his message would make it back to his mother even if he didn’t.

In other cities, especially in western Ukraine, protesters were seizing control of government buildings, often facing little or no resistance, and demanding that Yanukovych-appointed officials resign. Maidan was a nationwide movement, with more than two million Ukrainians participating in protests. Yanukovych offered to appoint two opposition leaders to the government and to grant an amnesty for protesters who left occupied buildings. But the crowds on Maidan were vehemently opposed to any compromise.

Dmytro Bulatov, a leading Maidan organizer, was found badly beaten, soaked in blood, with an ear cut off and his hands pierced by nails, as if he’d been crucified. Missing for eight days, he’d been left to freeze to death in the forest outside Kiev. The police suggested, astoundingly, that he had faked the whole thing. They tried to arrest him in the hospital but were stopped by protesters.

On February 18 there was another huge protest, this time in favor of restoring the constitution to its pre-Yanukovych form. It became a pitched battle. Snipers appeared on rooftops, shooting to kill.

When the violence began, Laima Geidar, a former LGBT activist, had started working as a medic. She wanted to rush to Maidan on February 18, but the police had closed the bridge across the Dnieper River, blocking crowds of people who, like Laima, were trying to get across to help. A crowd of people stood outside the hospital in Laima’s neighborhood, preventing the police from arresting wounded protesters. She helped organize a medical point at the Greek Catholic church. People would get stitched up and want to return immediately to Maidan. “Give me a pill for a concussion,” said one man who’d been beaten with a truncheon. Even a man with two broken hands wanted to go straight back.

During the next two days, Laima’s medical team found more than nine people who’d been shot in the left eye: evidence of the coldest and most expert sniper fire.

I watched on the live feed as priests and an imam prayed on the Maidan stage, surrounded by flames. The protesters kept up a steady, dull drumbeat, banging on shields and anything else available. This was the music of revolution: a clatter, a din, anonymous musicians cloaked in smoke. From across the ocean, it looked like the end of the world, but my friends in Kiev assured me that it was less frightening to be there than to watch it on television.

“When Maidan was going on,” my friend Mitya told me later, “it felt like the only safe place; it was like a centrifuge. At the center you’re safe, but anywhere else the force will send you flying.”

From Black Square: Adventures in Post-Soviet Ukraine. Used with permission of W. W. Norton & Company. Copyright © 2016 by Sophie Pinkham.

Sophie Pinkham

Sophie Pinkham is a professor at Cornell University and a former NEH Public Scholar. Her writing on Russia and Ukraine has appeared in the New York Review of Books, New York Times, Guardian, New Yorker, and Harper’s. She lives in Ithaca, New York.