Where Does Palestine Begin?

"When a house gets demolished in East Jerusalem, does it stop being Palestine?"

I’m sitting in my office in New York, lingering over the draft of an email I need to send to the staff.

It explains my complicated trip through Saudi Arabia and Germany and Egypt, finally to Palestine for the festival. I feel that I am not straightforward enough for these colleagues, most of whom are three or four hours away from home, their families a city or a state away instead of scattered across continents.

But I know that this is not exactly the source of my hesitation. It’s the word Palestine. But what else could I call it? The Territories? The West Bank? Do I need to hide it, the way I hide it at the Allenby Bridge crossing? Do I need to soften it for this audience by placing it next to the word Israel? Can a word be made so absent without people becoming alarmed when it does appear?

What else are we hiding when we hide Palestine?

I send the email. Two people mention it to me, in separate conversations, before I leave. One registers her surprise, calls it brave. Another is excited because he has found an ally in a cause he has not been able to express his passion for to any other colleague.

This is a press-freedom organization.

A manager, whom I respect and am friendly with, crosses her arms in front of her chest and keeps them there, hurries me out of her office when I come in to say goodbye.

The political choices that we make about language, about names, are more than tools for use in a broader effort. They are the effort, and the battle.

Can you have a literature festival in Palestine without including Israel? Without inviting Israeli writers, without going to Israeli audiences?

There is often confusion when talking about Palestine as a geographical place. Most people don’t know that Gaza and the West Bank are as unreachable from one another as two places can be. You cannot reach either one without going through a border or a checkpoint controlled by Israel. Sometimes you can reach Gaza by going through Egypt, Israel’s ally in its siege.

You cannot be in Palestine without saying your grandfather’s name to Israeli officials at the border or the airport. You cannot eat in Palestine without buying or dodging Israeli products. You cannot buy anything at all without using Israeli currency.

In Palestine, Israel is everywhere.

We drive through Ramallah, capital of politics and finance for the would-be Palestinian state. Here you buy your Jawwal or Wataniya SIM card for use in the West Bank. Palestinian phone operators have not been allowed to provide 3G, although we hear that might change now.

Some people manage to buy Israeli SIM cards, either in Israeli cities or from rough neighborhoods near the separation wall, where they are on sale along with other contraband such as drugs and weapons. Communication is a serious offense. The options are Cellcom and Partner, which used to be called Orange until Orange pulled out after campaigning by the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions Movement.

These SIM cards will pick up 3G from settlement communication towers sometimes, especially in the hillier parts of Nablus and Ramallah, near land with the densest settlements. If you are looking for a West Bank settlement, look for a tower. They go up first, poking out of the hills like flagpoles, and the settlers follow.

We go to shattered, buried Palestine in the old city of Hebron. We look up, and Israel lives above the wire mesh which catches its rocks, its garbage, although not its urine. Israel is in the upper floors of houses taken over and occupied by settler families, or turned into watchtowers for the soldiers who protect them. Palestine on the ground floor, on the street level, and Israel between the wire mesh and the sky.

We drive north to look for Palestine in Haifa. We have hidden our Palestinian friend in the back of the bus. Hidden is too strong a word here perhaps. She sits in plain sight, sunglasses on, flanked by white writers on either side.

The bus is stopped at a checkpoint. A man with a machine gun and a baby-blue shirt gets on the bus, a woman in khaki behind him. He asks for the group leader. Omar gets off the bus with him. They are gone for about 20 minutes, standing nearby, talking. On the bus the writers are filled with questions; some are worried. Our Palestinian friend is calm.

They come back on the bus, angry that one of the writers had been taking photographs out of the window. The man with the machine gun asks to see the phone, and to delete the photos. The offending writer wants to know what authority he has to see his phone or his passport.

The man tells us he is a civilian. He shows us a card to prove it. His machine gun is the width of the aisle between the seats.

Eventually the writer backs down. He knows that he can recover the photos instantly.

We continue our drive. The traffic had grown worse during our hold-up at the checkpoint, and we will be late to Haifa. But we are late to Haifa every year; one year we were so late that the writers had to be hurried into borrowed bathrooms in which to collect themselves after the three-hour drive before going immediately on stage half an hour late.

The road to Haifa becomes coastal, and it is poster-perfect: designed landscapes, the plumper, softer light of the seaside, the sky paler near the water. The wall is far from here.

When we reach Haifa the bus makes two stops. We have split the group between the only two Palestinian-owned hotels in the city. At the first hotel I call out the names of the people who should disembark now, tell them to get their bags and check in, tell them where and when the next meeting point will be. It is now the fourth day of the festival, and I can feel them getting annoyed, wanting to break free and have a beer by the sea and walk around this pretty town and not have to deal with the slowness of a group splitting between hotels, one of which doesn’t provide breakfast. Can’t we just stay in the Marriott?

At night our audience finds us. Young and cool, arty and multilingual. After the event we go to Masada Street, where the cafes and bars are open to a mixed crowd of Jewish Israelis and Palestinians in the daytime. At night the socializing is segregated. We stick to Eleka and a couple of other Arab-owned bars.

A week after the festival has wrapped a drunk man in Ramallah says, Don’t be enchanted by Haifa. Haifa is corrupt, her beauty is a cheap mask. Go to the abandoned villages, go to the Muthallath, go to Um el-Fahm; there you will find Palestine.

So then where are we now?

He orders another Heineken.

What of the Palestine of camps, of exile, of statelessness?

When a house gets demolished in East Jerusalem, does it stop being Palestine? When, in which moment? When the first brick drops or when the last is cleared?

When the Palestinian Authority arrests teenagers days after the Israelis have released them, do they leave the same absence? Where does Israel stop and Palestine begin in the network of incarceration?

When you are driving into Ramallah, there is a sign that warns you are entering Area A. It is forbidden by Israeli law, and it is unsafe, the sign says. On the other side of the checkpoint children sell cassette tapes, pillows, kitchenwear.

There is no security check for those going in to Ramallah. Anyone can drive in or walk through. Going the other way, leaving Area A and going into Jerusalem, is a different story.

So we go through areas A, B and C, a rambling bus of privileged-passport holders, popping up with events which we can only run with the help of patient friends who show us their Palestine and share their stage.

We do not schedule ways to engage with Israel, because Israel is everywhere in Palestine. It may not be the version that Israeli officials and cultural actors would like seen. But perhaps the role of literature and art should be to look for what is hidden, what is obscured, what is made harder and harder to reach.

There is a point when you are entering Bethlehem where you can see the wall’s curve through a field of olive trees. The scene has it all: the idyllic beauty of the land, the concrete abruptness of its severance, the two together surreal. Every year I try to snap a photo at the right moment as the bus drives by but it always appears too suddenly, and blurs.

__________________________________

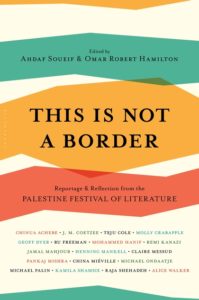

From This is Not a Border: Reportage & Reflection from the Palestine Festival of Literature, ed. Ahdaf Soueif and Robert Hamilton. Used with permission of Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2017 by Yasmin El-Rifae.

Header image by Léopold Lambert.

Yasmin El-Rifae

Yasmin El-Rifae is a co-producer of the Palestine Festival of Literature. She is at work completing her first book, a history of an extraordinary feminist resistance group within the Egyptian revolution. @yasminelrifae