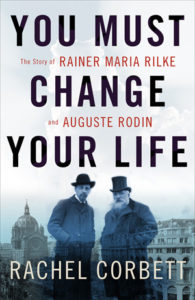

When Young Rilke Moved to the Big City and Met Rodin

A 26-Year-Old Poet Alive to the Sights of Paris

Rilke arrived at Paris’s Gare du Nord railway station on a steamy August afternoon. Travelers were advised to immediately entrust their belongings to a porter to avoid thieves and pickpockets who preyed upon tourists bewildered by the crowds at the enormous glass station.

As he stepped out into the street, his shirt buttoned to the top and trousers creased, Rilke’s eyes bulged at the sight of this alien city. He had never seen an industrialized metropolis like this before—the motors, the speeds, the shapeless enormity of the crowds. Machine-powered labor had replaced human jobs and pushed many of the disenfranchised workers into the streets. He spotted disease-ravaged bodies split open with abscesses, trees scorched bare by the sun, beggars with eyes “drying up like puddles.” There were hospitals everywhere.

The crowds of people reminded him of beetles, crawling through garbage, scurrying to survive beneath the giant footsteps of life. Before the advent of big cities and public transportation, one rarely had to look at other people. Here they were everywhere, forming masses that seemed to contain no individual faces, only needs.

The visual field corresponded with the economic spectrum, so that in a single pan of the eye one saw the full gamut of the city’s wealth and poverty. At the bottom were the ragpickers fashioning shantytowns out of the waste of the bourgeoisie, whose carriage horses trotted overhead, leaving trails of litter and horse manure behind them. Somewhere in the middle were the dogs, often quicker than the beggars at snatching up scraps of food.

Parisians seemed to feel the will to live more keenly than others. Rushing commuters “made no detour around me but ran over me full of contempt,” as if Rilke were a pothole in the street, he wrote. The newfangled subways and streetcars, meanwhile, sped “right through me.” It soon became clear that no one would stop to help him here. Unlike in Munich, they did not care that he was a young, struggling artist. Everyone was struggling here just to survive.

But as Rilke hopped over heaps of trash on the way to his hostel, he began to feel terribly excited. The sights were all so new—the bridges, the wagons, the brick streets—that it felt as if they had been made for his eyes alone, like the set of a play to which no one else paid attention. He pronounced the foreign street names to himself and let the rhythmic French syllables loop around his head: André Chénier, vergers . . . Paris was filthy, yes, but at least this was the filth of Baudelaire and Hugo, he thought.

By the time Rilke crossed the Seine to reach the Latin Quarter he felt feasted upon and exhausted. The neighborhood had since lost its bohemian reputation as artists began climbing the hill to Montmartre, where they squatted in maquis or moved into the fabled Bateau-Lavoir studio building, as Picasso and Kees van Dongen would soon do. Now the quarter was dominated by students from the Sorbonne, just down the street from Rilke’s hostel on the narrow Rue Toullier.

Opening the door to his cramped room gave him little comfort. There was an armchair indented by all the greasy heads that had previously rested on it, a threadbare rug and a pail with an apple core left in it. A single window looked out onto a stone wall, a view that Rilke would accuse of stifling his breathing over the next five weeks. Worse, the dozen windows on the building seemed to stare back through his curtains, watching him “like eyes.”

He lined up his pens and papers into orderly rows on the desk and lit the wick of a kerosene lamp. He sat down to reflect on his journey thus far, leaning back into the hollow of the chair, already molded into the slumped shape of a weary traveler.

At just before three o’clock on Monday, September 1, Rilke walked from his hostel along the Seine to Rodin’s studio in the Marble Depot to introduce himself to his future master. The courtyard of the building looked as rough and undeveloped as a quarry, with sheds lined around the edges for studios. Sometimes a sign hung on the door to Atelier J informing visitors, “The sculptor is in the Cathedrals.”

Luckily that was not the case on the day that Rilke knocked. The door opened onto a dark room, “sparsely filled with gray and dust,” he noticed. There were a few bins of clay and a pedestal. Rodin had cropped hair and a soft gray beard. He stood scraping at a chunk of plaster in his hand, paying no attention to a model posed nude before him. His clothes were hardened with the splatter of earthy pastes. He was shorter than Rilke expected, yet somehow more noble-looking. A pair of rimless glasses balanced on his nose, which extended from his forehead like a “ship out of a harbor,” Rilke observed.

When the artist looked up at his young visitor he stopped what he was doing, smiled shyly, and offered a chair. Next to the lionesque artist, Rilke looked even more like a mouse. His face gathered into a point right where his nose joined a few droopy whiskers. He was 26 years old, narrow-shouldered and anemic, while the stout Rodin, then 61, plodded around heavily, his long beard seeming to draw him even closer toward the ground.

Rilke labored through all the French pleasantries he had memorized before Rodin, thankfully, took over the conversation. The sculptor gestured around the room, pointing out one remarkable object after another: There’s a plaster hand, there’s a hand in clay, he would say. Here’s a création, there’s a création. How much more exquisite that word, création, sounded in French than it did in German—Schöpfung— Rilke thought. There was a surprising lightness to the man. He had a laugh that was simultaneously joyous and embarrassed, “like a child that has been given lovely presents.”

After a while, the artist went back to work, inviting his visitor to stay in the studio and observe for as long as he liked. Rilke was astonished to see how easy Rodin made sculpture look. He approached a bust like a child making a snowman, rolling up a ball of clay and plopping it on top of another ball to make a head, then cutting a slit for the mouth and two thumbholes for eyes. As the work progressed, so did Rodin’s energy. Rilke noted the way the artist would lunge at his sculptures, the floor creaking and moaning under his heavy feet. He would fix his heavy eyes on a detail and zero in so close that his nose pressed up against the clay. With a few pinches of his fingertips, a face, and from the rough gashes of his pick or chisel, a body. He worked rapidly, as if “compressing hours into minutes,” Rilke noticed.

Rilke could have watched Rodin all day, but he did not want to impose on his first visit. He told the sculptor that he would be on his way and thanked him for the fascinating introduction to his work. To Rilke’s delight, Rodin invited the poet to join him again the next day. He would be working at his country studio then and it might be useful for Rilke to see the way things operated there. The poet wholeheartedly agreed.

Rodin’s generosity with his time buoyed Rilke’s spirit when he returned home that evening. He could not have hoped for a more kind and engaging subject. “He is very dear to me,” he wrote to Westhoff that night. “That I knew at once.”

The next morning, Rilke rehearsed a few French phrases, put on a cheap but tidy suit and then boarded the nine o’clock train from Gare Montparnasse. He could hardly wait to see Rodin’s workshop in the suburb of Meudon, and to finally breathe in some much-needed country air.

Meudon was only twenty minutes southwest of Paris by train, but seemed to exist in another century altogether. The hills swallowed up the city’s smokestacks, which could be seen chugging in the distance. The old cottages slouched like sheep in a field, Rodin thought when he first visited this landscape. It had awakened in him the “untroubled happiness” of childhood. He felt so at home there that he bought a petite Louis XIII–style chateau called Villa des Brillants and built a studio on the property in 1895—two years after his split from Camille Claudel, who was likely a consideration in his withdrawal from Paris.

As Rilke’s train lurched toward town, the view did not charm the poet nearly as much as it did Rodin. The road leading into the station was dirty and steep and the houses cramped the Seine River valley too tightly. In town, all the cafés reminded him of the dingy osterias he had seen in Italy. It was not the setting Rilke had imagined for such an illustrious artist.

To be sure, Meudon was no Giverny, the lush suburb where Monet owned his compulsively manicured estate. Whereas the painter nurtured beds of exotic flowers and built a footbridge over his pond of water lilies, Rodin let his estate grow wild. Passing through the gates to the Villa des Brillants, Rilke crunched along an unpruned path paved with equal parts chestnuts and gravel. The simple red-brick building at the end of the drive was not much of a sight, either.

When Rilke knocked on the door, an apron-clad woman with soapsuds on her arms opened it. She stared at him, looking as tired and gray as an antique, while Rilke recited his French greeting and told her that he had an appointment with Monsieur Rodin. Just then the artist appeared at the door and invited Rilke in.

The sparsely furnished rooms reminded Rilke of Tolstoy’s austere home in Russia. There was no gas or electricity and Rodin did not hang paintings on the downstairs walls, in order to focus the view out the windows. The only decorations he displayed were his antiques, a growing collection of terra-cotta vases, classical Greek nudes, Etruscan artifacts, and broken Roman Venuses. There was a simple trestle table and a few straight-backed chairs, for Rodin believed that cushions were indulgent: “I do not approve of half going to bed at all moments of the day,” he once said. This led one visitor to remark that Rodin’s home “gives one the feeling that the act of living itself plays hardly any role for him.”

Rodin then took Rilke outside for a tour of the grounds. As they walked, Rodin began to tell Rilke about his life, but not in the way one might speak to a journalist on assignment. He understood that Rilke was a fellow artist, and so he framed his stories as lessons that the young poet might take as examples. Above all else, he stressed to Rilke, Travailler, toujours travailler. You must work, always work, he said. “To this I devoted my youth.” But it was not enough to make work, the word he preferred to “art”; one had to live it. That meant renouncing the trappings of earthly pleasures, like fine wine, sedating sofas, even one’s own children, should they prove distracting from the pursuit.

Rilke listened to Rodin’s advice as best he could through the rapid French. But whereas Rilke’s intense eye contact held his company close, Rodin rarely looked directly at listeners at all. The artist could become so absorbed in a topic that he sometimes forgot who he was talking to altogether, much less whether they were still paying attention.

When Rodin finally paused to take a breath, Rilke seized the opening to say that he had brought the master a small gift. He pulled out some pages of poetry and presented them to Rodin, who politely flipped through them. Although they were written in German, Rilke thought for certain he detected in Rodin’s nodding an approval at least of their form.

At noon, they sat for lunch at an outdoor table, joined by a rednosed man, a girl of about ten and the woman, in her late fifties, who had answered the door earlier. Rodin did not bother introducing Rilke to any of his guests. He addressed them only to complain that the meal was late. The woman’s face narrowed in rage and she slammed the dishes in her hands onto the table. She fired back some sharp words that Rilke didn’t understand, but their intent was perfectly clear. There could only be one explanation for such an intimate display of resentment at the table, Rilke thought. This must be Rodin’s wife.

Eat up! Rose Beuret barked at her guests. Rilke obeyed, nibbling nervously around the edges of his plate to avoid the meat. A waiter mistook Rilke’s vegetarianism for shyness and pushed more meat on him still. Rodin, oblivious to it all, noisily spooned himself mouthfuls as if he were dining alone.

When the meal was finally through, Rodin stood up and invited his visitor to join him in the studio. Relieved, Rilke rounded the corner of the house with Rodin and discovered that on just the other side stood the artist’s pavilion from the World’s Fair. After the exhibition closed in November 1900, Rodin had purchased a patch of land from his neighbor and shipped the entire pavilion to his property.

It served as a daily reminder of Rodin’s greatest success to date. He had sold two hundred thousand francs’ worth of art and received so many visitors that after he shipped the works to Meudon, the German publisher Karl Baedeker wrote the suburb’s mayor to inquire about the hours of the town’s “Musée Rodin.”

It occurred to Rilke that Rodin surrounded himself with his own sculptures the way a child does his toys. Nothing made the man happier than spending his days in the presence of his most prized possessions.

They then went to the studio, a long building encased almost entirely in glass. When Rodin opened the door, the sight left Rilke speechless. It contained what looked like the “work of a century.” The workshop pulsed like a living ecosystem, with white-smocked craftsmen carving away at hunks of marble, setting flames inside brick kilns, and hauling blocks of stone across the floor. The sun poured in through the arched glass, lighting up the rows of plaster bodies like angels, or “inhabitants of an aquarium,” as Rilke wrote. The bright whiteness seared his pale eyes like snow blindness; it was almost too much to bear. But that didn’t stop him from greedily trying to take it all in anyway.

After a few minutes, Rodin left his awestruck visitor to look around on his own. Rilke didn’t know where to begin. There were acres of half-made sculptures: limbs piling up on tabletops, a torso with the wrong head attached; arms and legs intertwined, striding and reaching. It looked like a storm had torn through a village and scattered body parts everywhere. There were casts of works that Rilke had only read about in books, including several yard-long sections of The Gates of Hell, uncast and strewn about shelves and display cases.

It became clear that Rodin prized hands above all other parts of the body. A well-informed visitor knew that to please the maitre one should ask him, May I look at the hands? They appeared around the studio in all configurations: old wise hands, a pair of clenched fists, two fingertips pitched into a cathedral spire. Rodin once claimed to have sculpted twelve thousand hands, only to have “smashed up” ten thousand of them. Just as he had previously spent years molding hands and feet for his old employer Carrier-Belleuse, Rodin now tested prospective apprentices on their facility with hands.

Rilke understood immediately the lesson contained in all these hands, often “no bigger than my little finger, but filled with a life that makes one’s heart pound . . . each a feeling, each a bit of love, devotion, kindness, and searching.” Whenever Rilke had described hands in his poetry they were always extensions into the world. They were need: a woman reaching for her lover, a child grasping its mother, a mentor pointing the way to a disciple. For Rodin, a hand was its own landscape, complete and internally resolved. It was not merely a sentence in the narrative of the body, it told its own story in lines and contours that added up like verses of a poem.

Rodin seemed to dream with his hands rather than his head, Rilke thought, enabling him to make his every fantasy real. Rilke only wished that Rodin would now take the poet into those transformative hands. He believed his calling was predestined; he just needed a master to animate it. Only Rodin, a man whose hands had set metal men into motion and roused heartbeats from stone, seemed to possess the life-changing touch that Rilke described in his Book of Hours:

I read it in your word, and learn it from the history of the gestures of your warm wise hands, rounding themselves to form and circumscribe the shapes that are to come.

By three o’clock, Rilke had filled his eyes with as much as they could take for one day. When he returned to Paris in the early evening, they were aching and exhausted by all they had seen. Still, he managed to dash a letter off to Westhoff that night to say that the visit had restored his hope in Paris and his decision to come there. “I am glad that there is so much greatness and that we have found our way to it through the wide dismayed world.” But now he was smearing the ink and ought to sign off: “My eyes are hurting me, my hands too.”

Rilke returned to Meudon a few days later. He again shared an awkward meal with Rodin and Beuret and, again, they were joined by the same young girl. (Rilke assumed it was Rodin’s daughter, but most likely it was a neighbor, since the couple only had a son.)

After lunch, the two men retired to a bench in the garden. The girl followed them and sat down on the ground nearby, turning over and inspecting pebbles from the path. A couple of times she came over and looked up at Rodin, watching his mouth move while he spoke, only to retreat again unnoticed.

A few moments later she came back, this time presenting him with a tiny violet. She placed it timidly in his huge hand and waited for him to say something. Instead, he looked “past the shy little hand, past the violet, past the child, past this whole little moment of love,” Rilke noticed. Rodin carried on talking to Rilke and eventually the girl gave up. He had been telling the poet about his education and had launched into a tirade about art school, which he believed taught students to slavishly copy their subjects. Most teachers were not like Lecoq, he said, who had taught him to see with his emotions, with an eye “grafted on his heart.”

The girl returned to make one final bid for the man’s attention. This time her bait, a snail shell, caught the master’s eye. He turned the shell over in his palm and smiled: “Voilà.” Here was a perfect facsimile of Greek art, he told Rilke. Its surface was smooth, its geometry simple, and the shell seemed to radiate with inner life. It bore the infallible laws of nature on its exterior, just like an exquisite figure model.

And, voilà, the snail might have also presented Rilke with an unexpected model of Rodin’s mind: an inwardly spiraling coil, oblivious to anything outside its own will. Rilke watched the girl recede once again into the background and he spoke up at last. Carefully suppressing his bulky German accent, he asked Rodin his opinion on the role of love in an artist’s life. How should one balance art with family? Rodin replied that it is best to be alone, except perhaps to have a wife because, well, un homme besoins une femme.

That evening Rilke took a walk alone in the woods to think about the harsh truths Rodin had shown him. The sculptor’s house was depressing. There seemed to be no love in his family. Yet Rodin knew all of this and didn’t care. He knew what he was, that he was an artist, and that was all that mattered to him. He abided by his own code, and no one else’s standards could measure him. He contained within himself his own universe, which Rilke decided was more valuable than living in a world of others’ making. In fact, it now seemed like a good thing that Rodin couldn’t understand Rilke’s poetry, nor speak any other language. That ignornace secured him more soundly within his sacred realm.

As the poet breathed in the cool, damp air he felt a space open up inside him. It was the relief that came from realizing now the destination, even if he did not yet know how to get there. He had faith in Rodin and his assurance that hard work would guide him.

When Rilke returned from the woods, everything looked different. He now saw only beauty around him: the still sky, three swans floating in the lake, rose blooms that bent from their vines toward the sun. Even the chestnut-littered driveway seemed to serve a new purpose: to guide the way forward. Life may grow thickly around its path, but the true artist stays focused on the way ahead. He must “look neither right nor left,” Rilke wrote to Westhoff that night. That was why great men like Rodin and Tolstoy each lived a meager life, “stunted like an organ they no longer need,” he wrote. “One must choose either this or that. Either happiness or art.”

One wonders how that news might have sat with Westhoff in Germany, caring for their daughter Ruth on her own. Rilke preferred to describe himself and Westhoff as artists first, on parallel but parted paths, rather than as a couple on the same track. He championed Westhoff ’s art but was less sympathetic to her frustrations over child-rearing. When she complained of exhaustion, Rilke told her it was healthy to be a bit tired. Sometimes he tried to sweeten this condescension with a word of pseudo-praise: You are so strong and courageous, he would say, “one night will be enough to relieve you of it.”

But that September, Westhoff did not acquiesce so easily. She insisted that she wanted to be in Paris, too, and to gain access to Rodin once more. Rilke agreed, but convinced her not to bring Ruth. Paris was no place for a child, he said. It was wretchedly expensive, the hotels were cramped, and there was no time for anything but work. Rodin felt the same way, Rilke told her. “I spoke of you, of Ruth, how sad it was that you must leave her,—he was silent a while and then said, he said it with a wonderful seriousness: Yes, one must work, nothing but work. And one must have patience.”

Westhoff arranged for Ruth to stay with her parents in Oberneuland, a town near Worpswede, and made plans to join Rilke the following month.

After just ten days with Rodin, Rilke sent his new master a letter. He confessed that it might seem strange to write since they saw each other so often, but he felt the language barrier prevented him from fully expressing himself. In the quiet of his little room he could work out the words to tell Rodin precisely how much he had inspired him. He had given him the strength to suffer through loneliness, to accept sacrifice and to “disarm even the anxieties of poverty.” He told him that his wife had agreed with him on this, and would be joining him in Paris soon. If they could both find work there, they hoped to stay indefinitely. He sensed that this journey would prove “the great rebirth of my life.”

Rilke also sent Rodin a few lines of poetry that had come to him during a recent stroll through the Luxembourg Gardens. “Why do I write these verses? Not because I dare to believe that they are good; but it is the desire to draw near to you that guides my hand,” he wrote. Rodin had “become the example for my life and my art.” Rilke knew his German verses would be incomprehensible to Rodin, but he longed to have the man’s eyes rest upon them all the same. Then he came to the real point of his letter: “It is not just to write a study that I have come to you,” he confessed, “it is to ask you: how should I live?”

We don’t know whether Rodin replied to the letter, but he offered the poet an open invitation to his studios over the next four months, which was all the encouragement Rilke needed to attach himself to Rodin at every possible moment. On the best days, the master invited him to Meudon in the mornings. Rilke would come prepared with a list of questions and they would sit by the pond or take a walk, their discussions often carrying on well into the afternoon. Rodin enjoyed coining new metaphors for his disciple and Rilke dutifully scribbled them down, like a pigeon pecking up bread crumbs. “Look, it only takes one night; in a single night all these gills are formed,” Rodin said once of a mushroom he plucked from the ground. Turning it over to reveal its underside, he explained, “That’s good work.”

Other days Rilke stood by in the studio to watch Rodin in action. He observed the way the artist wielded his tools like swords, remorselessly amputating limbs and heads with a single slice, slashing out swaths of clay until he ran out of breath. He chiseled into plaster until a cloud of dust filled the air. He was an additive sculptor and he broke his work down into parts before reassembling it. One minute he would snatch up a limb, like meat in a raptor’s talons, only to toss it into the trash a moment later. Sometimes he left bodies armless or legless entirely. The end result was often “not like a house, solidly built from top to bottom,” said the writer Jean Cocteau, “but only like part of a staircase, a balcony, or a fragment of a door.”

Rodin did not await inspiration, for some pure expression to flow from his soul onto passive materials, as Rilke had always done. To Rodin, god was “too great to send us direct inspiration.” Instead, it was up to the artist to create “earthly angels.” That’s why Rodin approached unformed clay “without knowing what exactly would result, like a worm working its way from point to point in the dark,” Rilke would write in the monograph. He would grab hold of it with his huge hands, work it over, spit on it and come to know it entirely, energizing the object and stirring it to life in the process. “The creative artist has no right to select. His work must be imbued with a spirit of unyielding dutifulness,” Rilke wrote.

Rodin’s hyper-animated style of sculpting produced no less dynamic bodies of work. Rodin manipulated light to enhance the sense of movement in his figures. When the geometry of the planes aligned just right, light would coast and dart across the surfaces and create the illusion of motion. Sometimes Rodin measured the success of this effect by employing a candle test, which illuminated the points of intersection between light and shadow. Rodin once demonstrated the test to a student at the Louvre. Arriving in the evening, just before the museum closed, he held up a candle to the Venus de Milo. He instructed the student to watch the light as he moved it around her contours. Notice how it glided across over the surfaces without jumping at a single hollow, rift or seam. Candlelight revealed all flaws, he believed.

Toward the end of Rilke’s first month in Paris, Rodin received a commission for a portrait that would take up an inordinate amount of time. He began working through the weekends and became too busy to continue the long chats with Rilke. The poet decided to give the artist some space by spending more time on his own in Paris. He could trace Rodin’s artistic development there by following the sculptor’s footsteps across his native city. Rilke went to the Louvre, where he was surprised to find himself suddenly formulating strong opinions about art: The Winged Victory of Samothrace was a “miracle” of motion to him now, whereas the Venus de Milo looked too passive and static for his liking.

Rilke spent a week, every day from nine until five, at the Bibliothèque Nationale, where Rodin had copied so many illustrations as a boy. Rilke’s goal was to do the same with the great French Symbolists, to trace the lines of Baudelaire and Valéry until he could glide across their grooves as smoothly as a fingertip on wet clay. He also pored over reproductions of the Gothic cathedrals—those “mountain ranges of the Middle Ages”—which he knew Rodin worshipped.

Each day after the library closed, the poet walked back toward his hostel along the Seine, pausing at the Île de la Cité to watch the sun set over the two towers of Notre Dame. The cathedral built for the Virgin Mary had been ravaged and restored in battle after battle, its ornaments were looted, yet its walls stood as strong as its namesake’s will was chaste. To Rilke, it was all the more beautiful for enduring that humiliation. This was the hour when the river turned to “gray silk” and the city lights glowed like stars fallen from the sky. Once darkness fell, people would once again pollute the air with their music and perfume, but cathedrals always offered asylum from the senses. Like a forest or an ocean, a cathedral was a place where the world hushed up and time stood still.

It’s nearly impossible to stand before a cathedral and not consider the labor that went into building it. The painstaking process of its creation is as compelling as the consummate structure. Rilke marveled at the thought of the cathedral builders returning to work day after day, year after year, setting one stone on top of another. The cathedrals would “never have been finished if they had had to grow out of inspirations,” he thought. The vision alone would have been too daunting. They were completed only because the artisans chose to make this work their lives.

Rodin’s mantra, Travailler, toujours travailler, contradicted everything Rilke had learned about the fusion of art and life in Worpswede. But the poet had spent years watching the clouds, anxiously awaiting a muse that never came. Rodin’s example gave him permission to act. Now, to work was to live without waiting. More than that, Rilke concluded, “to work is to live without dying.”

Excerpted from YOU MUST CHANGE YOUR LIFE: The Story of Rainer Maria Rilke and Auguste Rodin, by Rachel Corbett. Copyright © 2016 by Rachel Corbett. With Permissions from the publisher W. W. Norton & Company Inc. All rights reserved.