When They Put Lauryn Hill on the Cover of Time

On Evolving Standards of Black Beauty in the 1990s

Ask a black girl to recall her favorite Lauryn Hill memory from the 90s and at least one of them will probably recall a magazine—big, beautiful, and glossy. The end of the 90s was the print era’s last stand. That’s not to suggest that it was ever a neat divide, but in the predigital age the distinction between newspapers and magazines was this: Newspapers were what you turned to find out what was happening, but magazines were what you turned to figure out what mattered. Charged with the lofty duty of not only reporting but also interpreting culture, what a magazine chose to report not only rendered it visible, it also rendered it legible. Magazines had cultural capital.

If you were a black girl (and a writing or editing one at that), you waited anxiously to see if this was the month your favorite glossy would finally acknowledge your existence, all the while knowing that your appearances were exceedingly rare. If you were a black girl of the dark chocolate/dreadlocked/afroed/caesar-cut/hip-hop gen/afro-bohemian/nose-ringed/ghetto-born/Ivy League–schooled/Gucci-and-Timberland-loving variety, you already knew better than to try to find yourself in Essence, let alone Elle. In the case of the former (for which I wrote regularly), a frank, early convo with an editor who wanted to see me succeed produced this bit of wisdom: “Do yourself a favor,” she said. “When you pitch story ideas here, think of the Midwest and not of your five girlfriends in New York who you meet for cappuccinos.” Again, this is before the ubiquity of Starbucks, when coffee in New York was that thing sold in Greek cups in bodegas and cost 50 cents, and cappuccino-drinking black girls were so singularly rare MC Lyte dropped a whole track extoling the drink’s virtues in 1989.

The 90s was the decade that publishing, advertisers, and the film industry hadn’t been entirely disabused of the lie that black faces and stories could not sell to mainstream (read white) consumers. An example? Essence, the leading black women’s magazine in the nation couldn’t get the same fashion advertising as Vogue—despite the fact that both had a subscriber base that exceeded one million and research consistently demonstrated that black people’s combined buying power was an estimated half trillion. (It currently hovers at 1.3 trillion). Even when presented with these numbers, they countered by saying that black women weren’t their desired consumers.

Hip hop went on to disprove that when fashion houses discovered that Gucci on a rapper could transform its entire accessories market base, and Terry McMillan’s Waiting to Exhale proved publishers’ long-standing argument that black people didn’t read was false as hell—a revelation that gave birth to new genres like urban romance and hip-hop lit. It also paved the way for a new wave of black filmmakers including Spike Lee, John Singleton, and the Hughes and Hudlin brothers. Even with numerous successes, it was a battle that had to be fought time and again. Why do you think we organize and ride so hard for black filmmakers we want to see win on opening night? (Hey, Ava DuVernay, hey) Hopefully Black Panther’s success as, at least at the time of this printing, one of the highest-grossing superhero movies of all time will kill that convo once and for all.

So it meant something that by the end of the 90s, Lauryn Hill was not only on the cover of countless magazines, she was on covers that mattered. In 1999, when Time put Lauryn Hill on its February 8 cover, it had placed only 17 black figures on its covers throughout the 90s—out of a total of 525 issues. Only five—including Bill Cosby, Bill T. Jones, Toni Morrison, and Oprah Winfrey—worked in arts and entertainment. Lauryn Hill was the only musician. (See “Deconstructing: Lauryn Hill’s Rise and Fall, 15 Years After The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill,” Max Blau, Stereogum, August 23, 2013).

Akiba Solomon has a story she loves to tell: “When I first started out in magazines, I was at Jane. I remember going to my editors and saying, ‘I think we really need to do a feature on Lauryn Hill.’ They were like, ‘That Fugee girl? No. What’s the story?’ Then she came out on the cover of Bazaar, and I was like. ‘Fuck y’all.’ I was so happy because Bazaar was considered high fashion, dope and adult.” The Harper’s Bazaar double cover was a thing of tremendous beauty, featuring a solo image of beaming Hill in white slacks, red boots, and expertly flip-curled locs on one side and a denim shorts, faux fur, and beret-wearing Hill surrounded by gorgeous little black kids on the other. The cover was a radical departure for the magazine, which, despite being led by the legendary and absolutely visionary editor in chief, the late Liz Tilberis, was categorically whiter than white.

“She was really the first black woman artist that I’d ever seen do it like that. Like, ‘I’m not bending, and I’m not worried about what these white people are going to think.’”[/Lpullquote]“But it wasn’t just that people outside the culture were starting to see Lauryn,” Solomon reiterates. “It was also how she showed up. She went on that cover and she was still Lauryn. She was like ‘Y’all come to me.’ She was really the first black woman artist that I’d ever seen do it like that. Like, ‘I’m not bending, and I’m not worried about what these white people are going to think. I’m here and I am fashion. I’m just going to put some rollers in my locs.’ The corny people at Jane [didn’t] get her but these people at Bazaar, who are fucking dope, get it.”

Dr. Yaba Blay remembers three things about 1998. It was the year she moved back to New Orleans for graduate school after leaving the city at age 13, traumatized from incidents of colorism. It was also the year Miseducation dropped and Sudanese supermodel Alek Wek appeared on the cover of Elle magazine. She was the darkest-skinned person ever to do so. “In fairness, I don’t want to paint a picture like, ‘Oh, woe is me, I’ve never been seen as beautiful,’” says the Ghanaian-born and NOLA-raised Blay. “Prior to Lauryn, Foxy was the redeeming person in the mainstream to validate darker brown sisters’ color in a very public way. Seeing her being considered as beautiful meant that the potential existed that I could be seen as beautiful as well. But then there was this shift. Foxy was brown with a long weave. She gave you that girl and I loved her. But what made Lauryn Hill different from Foxy Brown to me was that Lauryn was real in a way that I could relate to. She was natural.” For Blay, who’d watched Lauryn’s hair grow from a short natural style with the Fugees to long locs, Lauryn offered much-needed confirmation that dark brown women with natural hair could also be considered beautiful in a way that Foxy Brown did not.

Furthermore, watching New Orleans, a city she’d known to be plagued with colorism, embrace Lauryn allayed a lot of her anxieties about moving back. “A lot of my childhood memories of New Orleans are riddled with colorism and very much wrapped up in people’s negative reflections of me. The first time I heard Lauryn, I was in New Orleans, and of course, she’s the hotness, and everybody’s into it. Lauryn also represented some level of ‘conscious’ which was also encouraging.” In a city that had been largely all about bounce music, Blay felt that Hill and other members of the neo-soul movement made room for other lifestyles and aesthetics. “It felt like New Orleans was catching up, so to speak.” Shortly after her return to the University of New Orleans, she discovered that she might have spoken too soon. “I get there, we’re rocking with Lauryn, I’m feeling good and I’m not feeling the colorism stuff as much, if at all. I’m making new friends and feeling good about myself.”

And then that November Blay saw Alek Wek on the cover of Elle. She was delirious with excitement. “I remember, very clearly, being in the checkout line of the A&P grocery store with one of my very best male friends and when I see the magazine, I literally start jumping up and down. It was the first time I’d seen a woman [with] my complexion on the cover of a magazine and somebody was calling her beautiful.” Blay was elated until she saw that her friend, who was also black, had a distinctly different reaction. “This Negro was pissed. And I was like ‘What the fuck is wrong with you?’” His response was a quick and hurtful reality check.

“White people making fun of us,” he said. “They know she’s not beautiful.” It was in that moment that Blay realized that Lauryn or no Lauryn, “We’re still here. We’re still here.” Even still, said Blay, Lauryn meant a lot to her. And she means a lot still. “Aesthetically for sure, but she also opened up a vibe that allowed a lot of people in New Orleans to be different and to think different. To come up off the ignorance for a little and think critically about ourselves. I’m not going to lie, though. That in that moment in that A&P line . . . That shit hurt my feelings in some real ways.”

I can relate. In 2001 I was the executive editor at Essence magazine when we made the decision to put Alek Wek on the cover. It was the 2000s and the reign of the supermodels as cover subjects was long over. That ground had been ceded to celebrities. Still, the editorial team decided the cover was both an affirmation of Wek’s beauty and recognition of the pioneering role she was playing for dark-skinned black women, both within the fashion industry and out. The Essence fashion and beauty team, particularly dedicated to combating negative beauty narratives about black women, rose to the occasion and created one of the most stunning images of Wek to date. It was the lowest-selling issue we had that year, accompanied by copious angry letters consistent with Blay’s A&P friend. It was heartbreaking and still my worst experience at the magazine in 20 years.

Alek’s story is relevant here, lest anyone discount the weight of the iconic position Hill occupied. Her image wasn’t just black, and it wasn’t just beautiful. It was uniquely relatable in a way that allowed black women to stitch themselves into her narrative and rewrite their own. The nature of beauty being what it is, a cultural currency unfairly assigned by the luck of the genetic draw, the impact of Lauryn’s beauty on other black women is rare. Beyoncé is undeniably a stunning woman but, as countless think pieces can attest, her beauty tends to be more polarizing than not. Lest this be relegated to merely light-skinned vs. dark-skinned shit, remember that Lupita Nyong’o’s, Anna Wintour “It Girl” moment immediately following 12 Years a Slave did not produce a similar phenomenon. We were able to stitch ourselves into Lauryn’s narrative because she had “That Thing,” that intangible every-black-girl thing that was indisputably us.

![]()

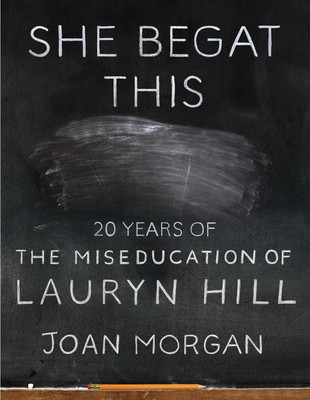

From She Begat This by Joan Morgan, courtesy Simon & Schuster. Copyright 2018, Joan Morgan.

Joan Morgan

A pioneering hip-hop journalist and award-winning feminist author, Joan Morgan coined the term “hip-hop feminism” in 1999 with the publication of When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost, which is now used at colleges across the country. Morgan has taught at Duke University, Stanford University, and The New School.