When the Goodness of a Woman Was Judged By the Bread She Baked

On Food, Sex, and Domesticity in the 19th Century

By the beginning of the 19th century, the moral pressures on women to produce good bread were intense. They came from multiple sources of male authority: the pulpit, the medical profession, and academia. Three of the leading proselytizers were from the Connecticut River Valley, wellspring of the First Great Awakening and stronghold of the Second: Rev. Sylvester Graham, Dr. William Alcott, and Professor Edward Hitchcock.

In his A Treatise on Bread, and Bread-making in 1837, Reverend Graham preached that refined white flour was a sign of man’s fall from his wholesome natural state to an artificial one, and advocated flour made from coarse ground whole wheat, heavy in bran. This flour still bears his name. At the time, it led Ralph Waldo Emerson to refer to Graham as “the prophet of bran bread and pumpkins.”

Graham also firmly believed that no commercial baker could make real bread; it was a quasi-religious calling reserved for women. When he wrote about food, his language was religious and sexual: “pure virgin soil” versus “depraved appetites.” He also campaigned against the evils of masturbation and excessive sex in marriage. Followers of his philosophy and his food lived in Graham boardinghouses in New York and Boston. They also spread Graham’s teachings to the Midwest, at Oberlin College, to health spas in upstate New York, and eventually to Battle Creek, Michigan, where they were instrumental in creating breakfast cereals.

Dr. William Alcott went further than Graham. Alcott believed that no bread should be leavened with yeast, because yeast was fermented, and fermentation equaled putrefaction. Yeast was already decaying and would damage the body. Alcott had to overcome his own aversion to unleavened, unbolted (unsifted), unsalted bread: “It appeared to me not merely tasteless and insipid, like bran and sawdust, but positively disgusting.” It was six months before he could force himself to become accustomed to this bread. Alcott echoed Graham as to who should bake the bread: the woman who has “a love for her husband and family,” because “no true mother, daughter or sister . . . can long remain ignorant of bread-making.”

Edward Hitchcock, professor of chemistry at Amherst College, believed that eating sparingly was the key to longevity, a philosophy also espoused by Nathan Pritikin in the late 20th century. Hitchcock cites examples of men who thrived on a Spartan diet and lived well past one hundred years of age. Hitchcock’s diet regimen consisted of twelve ounces of solid food and twenty of liquid per day. The solid food was heavy on bread.

Breakfast at 7:00 a.m.

Stale bread, dry toast, or plain biscuit, no butter………………….3 ounces

Black tea with milk and a little sugar………………………………6 ounces

Luncheon at 11:00 a.m.

An egg slightly boiled with a thin slice of bread and butter………3 ounces

Toast and water……………………………………………………3 ounces

Dinner at 2:30 p.m.

Venison, mutton, lamb, chicken, or game, roasted or boiled……..3 ounces

Toast and water, or soda…………………………………………..1 ounce

White wine, or genuine Claret, one small glass full………………1 ounce

Tea at 7:00 p.m. or 8:00 p.m.

Stale bread, biscuit, or dry toast, with very little butter……………2 ounces

Tea (black) with milk and a little sugar…………………………….6 ounces

Hitchcock went further than Graham and Alcott in his attitude toward women and bread. Under the heading “How far the blame is to be imputed to females,” Hitchcock condemns women for making food that is expensive and will kill their loved ones instead of making good, wholesome bread. He blames men, too, but he blames women first, for two and a half pages. His case against men is only one page.

All three of these men wrote and lectured extensively. Their writings were in the tradition of upper-class male-to-male lifestyle manuals that began in antiquity. Men have always looked to food for immortality, and although those early books contained dietary advice, they did not contain recipes until the Renaissance. In the Catholic countries, cookbooks were written by professional male chefs for the upper classes and contained recipes and advice about the court and its cuisine. The first cookbook written by a Catholic woman did not appear until after the French Revolution. Mme. Mérigot’s La Cuisiniere Républicaine, from 1794 or 1795, was a small pamphlet that consisted of 31 potato recipes, most of them one or two sentences long.

On the other hand, American cookbooks written by women come from a more recent tradition of female literacy that began with the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. Martin Luther said, “God doesn’t care what you eat,” and broke with the feast and fast days of the Catholic Church. With its emphasis on direct communication with the creator and personal knowledge of the Bible, Protestantism emphasized literacy, including female literacy. In the early modern period, upper-class men began writing manuals to instruct women and included recipes. By the second half of the 17th century, middle-class women in northern European Protestant countries were writing cookbooks. In 1667 The Sensible Cook was published in the Netherlands. Food historians believe that the anonymous author was a woman. In Britain in 1673, Hannah Woolley wrote The Gentlewoman’s Companion. In 18th-century England, Hannah Glasse, Susannah Carter, and E. Smith wrote comprehensive cookbooks that explained how to cook every type of food using sophisticated culinary techniques. The books also became popular in colonial America.

In the early republic, American women began to write cookbooks and books of household management themselves. These were also statements of philosophy, female-to-female communication. They spread rapidly because there was 100 percent literacy among women in New England by 1840.

Historians have not analyzed early American cookbooks in depth, and not with an eye to breadstuffs and chemical leavenings. Three books written in the 1980s by women historians began to examine women’s work in the home. In Never Done, her groundbreaking 1982 history of housework, Susan Strasser examined cooking in American households. However, she used only three cookbooks, by Sara Josepha Hale, Mary Randolph, and Catharine Beecher. The majority of the other information came from secondary sources written by men. In More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave (1983), Ruth Schwartz Cowan analyzed diaries, letters, and probate records to find out what housework was like for women in America. However, she did not use cookbooks. Glenna Matthews’s 1987 “Just a Housewife” used cookbooks by Amelia Simmons, Randolph, Beecher, and unnamed others from the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe and a private collection. In Eat My Words in 2003, Janet Theophano examined cookbooks more closely, but from an anthropological perspective.

Many of the women who wrote early cookbooks were what historian Natalie Zemon Davis calls “women on the margins”: orphans, widows, single women, or married women whose husbands for whatever reasons could not support the family. Amelia Simmons, who wrote the first American cookbook, American Cookery, in 1796, identifies herself as “an American orphan.” Wealthy Mary Randolph, from one of the First Families of Virginia, was the mistress of a tobacco plantation with 40 servants. In 1808, when political factors caused her family to lose their money, she opened a boardinghouse. In 1824 she wrote her cookbook, The Virginia Housewife. Eliza Leslie and her mother opened a boardinghouse when Eliza’s father died and they were desperate.

In 1827 Eliza wrote Seventy-five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats. Lydia Maria Child wrote The American Frugal Housewife in 1829 to support her family, because her husband was in prison. Catharine Beecher, one of the most influential domestic educators of the mid-19th century, author of A Treatise on Domestic Economy (1841) and Miss Beecher’s Domestic Receipt-Book (1846), never married after her fiancé died at sea. Like a 19th-century Phyllis Schlafly, Beecher spent her life traveling, speaking, writing, and telling women why they should stay home and bake bread.

American women cookbook writers were conscious of their identity as free people in a new country. They repeatedly referred to themselves and their cooking as American. They were outspoken about their vision for the new country and the place of food and female cooks in it. The Cook Not Mad contained recipes for “good republican dishes,” not recipes of “English, French and Italian methods of rendering things indigestible.” The book was published “in the fifty-fifth year of the Independence of the United States of America, A.d. 1830.” In the new republic, Election Day was a holiday and cause for celebrating. Simmons has a recipe for “Election Cake”; Beecher has “Hartford Election Cake.” On May 27, 1807, Martha Ballard wrote in her diary, “I made a Cake for Supper. it is Election day.” Simmons also has “Independence Cake” and a “Federal Pan Cake” of rye, cornmeal, salt, and milk fried in lard. Sarah Josepha Hale, founder of the Boston-based Ladies’ Magazine and daughter of a Revolutionary War officer, echoed Sam Adams when she organized a Committee of Correspondence to raise money for the Bunker Hill Monument.

Women who wrote cookbooks had to address the teachings of the popular Graham, Alcott, and Hitchcock. Hale would have none of them. Neither would Child. Hale considered bread making so important that she began The Good Housekeeper with it. She did include a recipe for “Brown or Dyspepsia Bread,” but grudgingly. “Dyspepsia” was a catchall term for any kind of indigestion in the 19th century. However, Hale refused to call it graham bread: “This bread is now best known as Graham bread—not that Doctor Graham invented or discovered the manner of its preparation, but that he has been unwearied and successful in recommending it to the public.” She says there is nothing wrong with the bread, “though not to the exclusion of fine bread.” Her recipe undercut Graham by telling readers to sift the flour first. This, of course, removed the fibrous particles that Graham believed provided the benefit.

Brown or Dyspepsia Bread

Take six quarts of this wheat meal, one tea-cup of good yeast, and half a tea-cup of molasses, mix these with a pint of milk-warm water and a tea-spoonful of pearlash or sal aeratus [sic].

Child, too, writing in 1832, had a recipe for dyspepsia bread, which she attributed to the American Farmer periodical. The ingredients were the same as in Hale’s recipe but in different proportions. The unintended effect of dyspepsia bread was that Americans became habituated to sweeteners in their daily bread, which had previously been unsweetened, and to thinking of sugar and molasses as healthy. Child also mentions that “Dyspepsia crackers can be made with unbolted [unsifted] flour, water and saleratus”—the beginning of graham crackers. In the 21st century, the first ingredient in commercial graham crackers is sugar.

Even if they disagreed with Graham and his followers, women had other moral issues connected to bread. In The American Frugal Housewife in 1844, Lydia Maria Child exhorted women to “make your own bread and cake” and stopped just short of accusing women who did not bake their own bread of being guilty of one of the seven deadly sins, sloth: “Your domestic or yourself, may just as well employ your own time, as to pay [commercial bakers] for theirs.” Sarah Josepha Hale (1841) did speak of food consumption in terms of “sin.” In this category she included eating anything immoderately. The underlying issue: “there is great danger of excess in all indulgences of the appetites,” making the unspoken connection between food and sex.

In two books, Catharine Beecher also made bread baking the moral measure of a woman. Miss Beecher’s Receipt-Book was a supplement to her Treatise on Domestic Economy. This manual on “every aspect of domestic life from the building of a house to the setting of a table” was extremely influential and was even on the curriculum at Ralph Waldo Emerson’s school. Both of Beecher’s books provided the platform by which she promulgated what her biographer, Kathryn Kish Sklar, calls Beecher’s “evangelical leadership to meet the threat of national wickedness and corruption.” Bread baking was at the forefront of the crusade.

The connections between cooking and morality were not only in cookbooks. They also appeared in 19th-century American novels. Mark McWilliams found that “for novelists as varied as Fanny Fern, Caroline Howard Gilman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Susan Warner, women who cook well serve as moral exemplars while women who cannot face social stigma.” However, cooking well was not enough. An additional burden was that women had to bake bread, which was strenuous manual labor, time-consuming, and messy, and they had to make it look effortless. Feminist scholar Margaret Beetham points out that in the 19th century, “it was an important part of the masculine fantasy of the domestic [middle-class femininity] that the work of maintenance was invisible.”

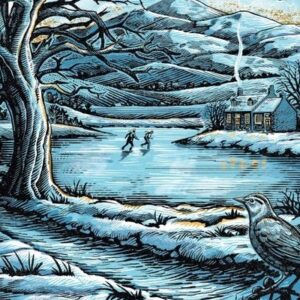

This was not solely a male fantasy. Women internalized it. In The Minister’s Wooing, her 1859 novel, Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote: “The kitchen of a New England matron was her throne room, her pride; it was the habit of her life to produce the greatest possible results there with the slightest possible discomposure.” Her main character personified the “angel of the hearth,” whose four virtues were piety, purity, domesticity, and obedience.

This Victorian idealized image of the housewife as unflappable and perfectly groomed endures. It was popularized in the 1950s and 1960s on television shows such as The Adventures of Ozzieand Harriet (1952–1966), Father Knows Best (1954–1960), and Leave It to Beaver (1957–1963).

The epitome of this ideal, which persists into the 21st century, is Martha Stewart.

__________________________________

From Baking Powder Wars: The Cutthroat Food Fight That Revolutionized Cooking. Used with permission of University of Illinois Press. Copyright © 2017 by Linda Civitello.

Linda Civitello

Linda Civitello teaches food history in southern California. She is the author of Cuisine and Culture: A History of Food and People, winner of the Gourmand Award for Best Food History Book in the World in English (U.S.).