When “Serious” Writers Write Books For Kids

A New York City Book Collection Highlights Authors Who

Dabbled in Children's Lit

Once upon a time Ken Kesey wrote an endearing tale about a wily squirrel and a hungry bear. The unlikely picture book was one of two written by Kesey nearly three decades after his well-known 1962 novel set in a psychiatric hospital, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Who knew?

Kesey—as well as Robert Graves, Eudora Welty, and William Faulkner—are among the writers pursued by 88-year-old book collector John Blaney. A born-and-bred New Yorker, Blaney has collected first editions of 20th-century authors for 50 years, amassing about 3,000 volumes before changing direction a few years ago. He said he was “priced out of the market,” but, “at the same time, it occurred to me, son of a gun, some of these authors also wrote a children’s book.” So he began to create a complementary collection, seeking out the children’s and YA books written by the authors already on his shelves. “And the good news was, not only were they cheaper, but they were thinner … and they took up less space!”

An exhibition of Blaney’s books titled They Also Wrote Children’s Books, which opened at New York’s Grolier Club in early March (but swiftly closed due to Covid-19), brilliantly juxtaposes each author’s juvenile and adult achievements.

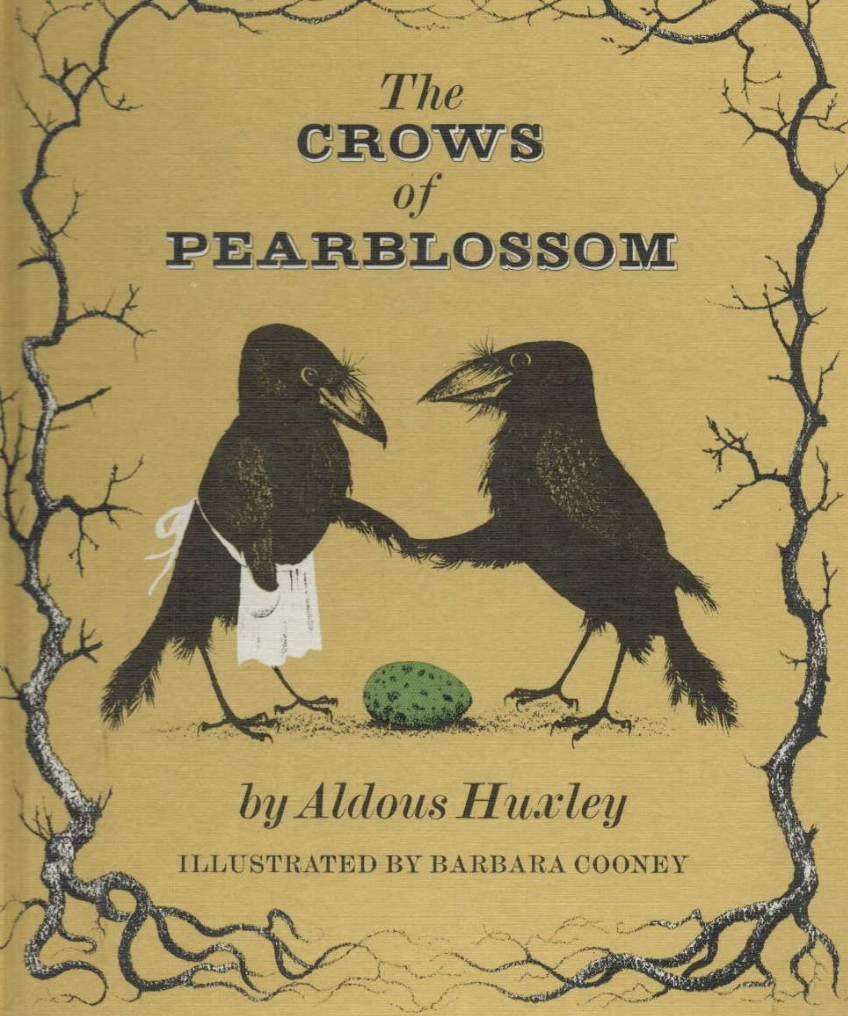

Aldous Huxley is one example who catches you off guard. Next to a first edition of his dystopian classic, Brave New World, sits a vibrant picture book called The Crows of Pearblossom, illustrated by two-time Caldecott Medal-winner Sophie Blackall and published in 2011. Written in 1944 for his niece, Olivia, the story features a clever crow couple whose egg keeps disappearing until they set out to find the thief. First published in 1967, it was his only children’s book and, like James Baldwin’s Little Man, Little Man—the 1976 first edition of which is in Blaney’s collection—it was long forgotten until a reissue gave it new life.

Although Ernest Hemingway’s nickname was “Papa,” it didn’t have anything to do with children’s books, or even children for that matter. In Blaney’s exhibition, a first edition of A Farewell to Arms (1929) is paired with A Good Lion, first published in an Italian magazine, and then in Holiday magazine in 1951, and finally in a limited edition book in 1998. It is, joked Blaney, “the most ill-advised book for a child,” adding that the main character, a lion, leaves his home in Africa and flies to Venice to order himself a “very dry martini with Gordon’s gin.”

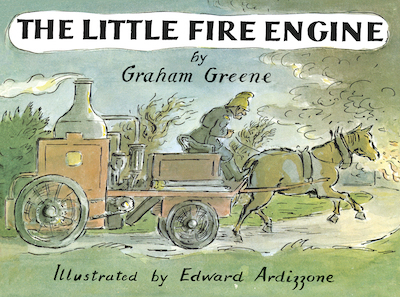

What can be gleaned from Graham Greene’s foray into children’s publishing also borders on sordid. On exhibit is a first edition of The Third Man, a mystery published in 1950, and a first edition of The Little Horse Bus, published in 1952. Greene wrote four children’s books for this series, including The Little Train, The Little Fire Engine, and The Little Steamroller, all illustrated by his lover, Dorothy Glover (pen name Dorothy Craigie), with whom he also collected detective fiction. It was, perhaps ironically, his affair with Glover and others that provoked his estrangement from his own children. The Little Train (1946) was originally published without Greene’s name on it. As Blaney explained, “Some people say Graham Greene did not want his name on this, his first children’s book, because he thought it would diminish his reputation as a serious novelist.”

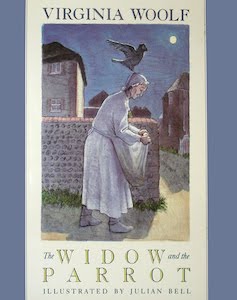

Colossal ego aside, one might argue that Greene’s name was the selling point for the other three, and most of the authors featured in They Also Wrote Children’s Books embraced that idea. Of the 39 couplets on view, most are cases in which the author was first known for adult fiction and then capitalized on that standing to publish a book for younger readers. One major exception to that is Virginia Woolf. The first American edition of her last novel, Between the Acts (1941), illustrated by Vanessa Bell, is matched up with The Widow and the Parrot, a story she wrote for her nephew Quentin Bell, who discovered the manuscript 60 years after its completion. It was then published in 1988, illustrated by Woolf’s grandnephew, Julian Bell.

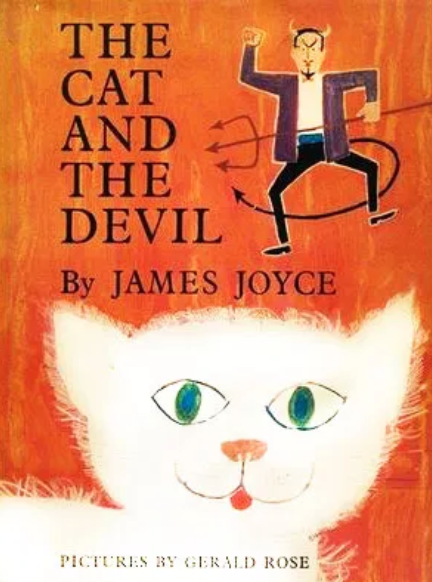

As in Woolf’s case, James Joyce also wrote a charming fable for a family member, published posthumously in 1964 as The Cat and the Devil, which, said Blaney, “happens to be a pretty good children’s book.” Blaney’s copy was inscribed by the illustrator, Richard Erdoes, who opted for neo-medieval imagery. He seemed to like the book better than Henri Matisse liked Ulysses; when he illustrated the 1935 Limited Editions Club edition of Ulysses, exhibited alongside The Cat and the Devil, he portrayed Homer’s Odyssey instead, which must have irked Joyce. Still, the book is beautiful, and highly collectible.

Of all the authors in his collection, Blaney said he feels most connected to Kurt Vonnegut. Although he is a self-professed “autograph paparazzo” who haunted book signings and hounded authors for signatures, his signed first edition of Slaughterhouse-Five (1969) was acquired while Blaney, formerly an advertising account executive at Ogilvy & Mather, was working on a campaign that used photographs of famous authors. (He also worked on a famous Maxwell House commercial, pumping water into the percolator to the right beat.) He met Vonnegut on February 14, 1970, the 25th anniversary of the Dresden bombing depicted in the novel, and when Vonnegut signed his book, he dated it too. “It was the only book he dated,” said Blaney, “every other book he just signed.”

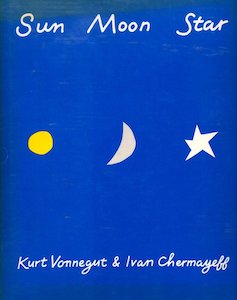

Vonnegut’s celebrated war story is a strange bedfellow of his 1980 children’s book, Sun Moon Star, a chronicle of the baby Jesus, but that’s the power of this collection: to learn something new about an author you thought you knew.